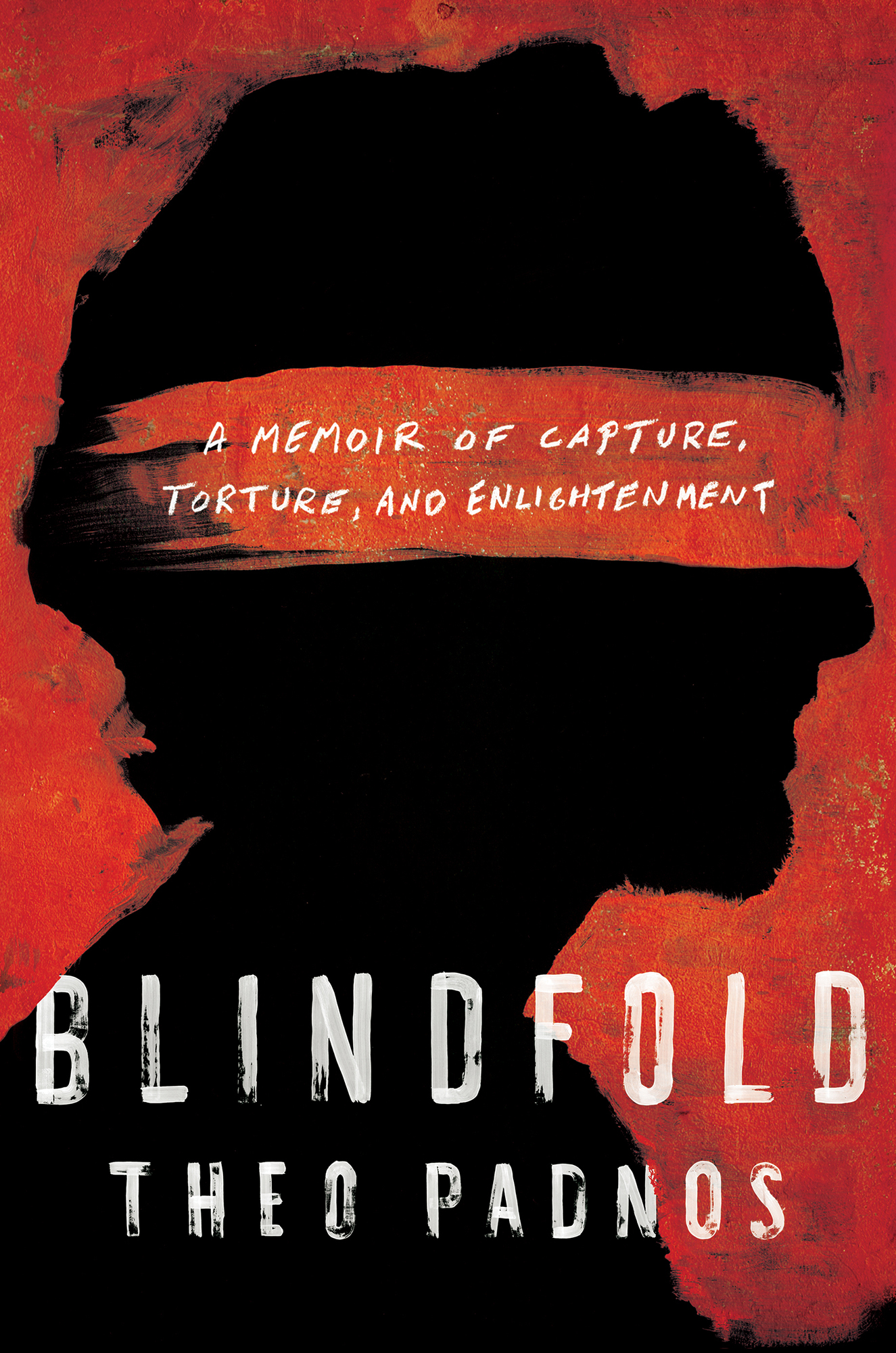

Theo Padnos - Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment

Here you can read online Theo Padnos - Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Scribner, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment

- Author:

- Publisher:Scribner

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Theo Padnos: author's other books

Who wrote Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Theo Padnos

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition February 2021

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Jacket design and artwork by David Litman

Grunge texture by Lubilub/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-9821-2082-5

ISBN 978-1-9821-2084-9 (ebook)

To Jim Foley, Peter Kassig, Steven Sotloff, and Kayla Mueller. I wish you were here to tell your stories.

O n my first day in my first prison, the Eye Specialist Hospital of Aleppo, Syria, the captors gave me a blindfolda grime-stained scrap of fabric they called the cloth. Before every interrogation and during my twice daily excursions through the hospital corridor to the bathroom, they made me tie it over my eyes.

I knew everything about that blindfold. It lay on the floor of the cell I was occupying then, next to a pee bottle, a water bottle, and some bits of bread crust I was saving up. It was an early springtime green. It felt soft in my fingers. It had been decorated with dozens of tiny violets. I became attached to this blindfold, perhaps because, in that world of al Qaeda prisons, it was my only possession.

This cloth stayed with me through many cellmates, sessions of torture, escape attempts, and transfers from one prison to the next. Sandals came and went, as did spoons and pee bottles. I wore the same pair of bloody sea-green hospital pants for half a year. Eventually, they vanished, too. I held on to the blindfold.

At first, I hated this object because it meant total helplessness for me and, for them, a deeper kind of control. But it was such a tattered, threadbare, throwaway scarf that, if I tied it right, it could be used like a veil. I could see, and they didnt know I could see. Later, it occurred to me that it had probably once belonged to a woman (because what would a Jebhat al-Nusra warrior want with purple flowers?), that it might have been used in her kitchen or to keep her hair in place, and so I started to think of it as my connection to the world I had lost: women, civility, cooking. I needed to hold on to it for this reason. I clove-hitched it around my neck once. It was long enough, when rolled into a rope, to work as a noose. That scarf was my emergency escape route. I wanted it nearby in case it became clear that a quiet slouching into soft fabric, followed by deep sleep, would be preferable to whatever horror they meant to videotape, then send out to the world.

There came a time when this head scarf soaked up my blood. My hair was coming out in handfuls then, like a dying sort of seaweed. When I removed the head scarf, there was more hair to it than there was fabric. I used it as a bandage now and then. It absorbed the sorts of things bandages absorb.

Through the months, the scarf mopped up my sweat and wiped away graffiti I scratched into the walls, then erased in a panic when a guard warned that my defacing their prisons might bring on the car battery. It soaked up soup I had spilled on the floor. Sometimes, when I had spare food, I hid the food within the cloth.

I had no pen during my first eighteen months, and no way to tell myself what was happening to me. The blindfold, I began to think, was a register. Its blood, pus, and hair were the outward, visible marks of an ordeal that was above all else a trial of the spirit. And it had kept me safe. Wheres the cloth? they used to shout when they opened up the cell door. If I had it in my hand and was busy blindfolding myself, they could see I was complying with the prison rules. They didnt hit me. So I brandished it at them like a talisman, wrapped it around my eyes, and then, in this state of compliance and fleeting safety, I walked out from my cell, into their world.

I could see. I watched them at prayer, at study, in their kitchens and their meeting rooms. I was an unobserved observer in their little Islamic stateso it felt to meand my safety within it was because of the purple flowers I had tied around my head. Those flowers helped me see. The blindfold was my laissez-passer. It was the little patch of magic carpet on which I traveled.

Now and then, other prisoners needed it. Someone was about to be interrogated. Or led away to god knows wherea torture chamber, the trunk of a car, a grave. Do you have a cloth? a guard would ask, banging on my cell door. I gave mine to Yassin yesterday, I would lie, or I would sigh: A cloth? No. By god, I have nothing.

Over time, it began to seem to me that the captors meant to tamp down all my senses and that, as a consequence, the senses had woken up. About a year and a half into my ordeal, they decided to allow me a pen and paper. Soon, I found myself writing a story. When I began it, I didnt know much about the plot of this story but I did know that my blindfold would be important in it. For me, that blindfold represented the power of my senses over their ambition to shut them down.

Now I think that in those first months in the eye hospital, they wanted total disorientation for meand for the other fifty-odd prisoners they kept in windowless cells in that basement. The blindfold was meant to detach me from everything I knew about the world, including my name, which, in those days, became Filth and sometimes Ass and other times Insect. Perhaps I did become a bit unmooredbut as this was happening, my senses were on high alert.

For instance, in a prison, you learn to know whats going on by smelling the air. The prisons in Syria smell of charred wood, burning trash, people throwing up in their cells, and the floor-cleaning fluid with which they mop up the scenes of their crimes. In the evenings, they smell of the feasts the fighters make for themselves: roasted chicken, cardamom in the coffee, piles of steamy, fluffy rice. On Fridays, the day of prayer, they smell of shampoo. When there is torture, they reek of the patchouli oil the men in black put in their beards. Every time you smell the oil, you know those men are on their way into the cell block.

Of course, I also listened. In the blackness of a cellor when they took charge of tying the blindfold and so cinched it down tightmy ability to make sense of sound was all I had. Over time, I began to think that the auditory faculty runs much deeper than we know, that footsteps and whispers proceed directly to the lizard part of ones brain, and that sounds had helped me see just as my blindfold helped me see.

In some of the prisons you hear the interrogations in high fidelity, as if theyre happening in the cell next to yours. Sometimes they do happen there. As theyre flogging the guy next door, they will sometimes tell you to thrust your face to the floor or against the wall, and you might well pretend to have heard nothing at all, but you cannot keep yourself from knowing whats going on then. Elsewhere, its the squawk of the commanders two-way radios that sinks into your consciousness, and the codes they use among themselves when they are discussing the next checkpoint to be attacked, or the fate of such and such a prisoner. Sometimes its the sound of a certain commander as he barks at his underlings that awakens your senses, and other times its the conviction in the fighters voices as they sing their anthems.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment»

Look at similar books to Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Blindfold: A Memoir of Capture, Torture, and Enlightenment and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.