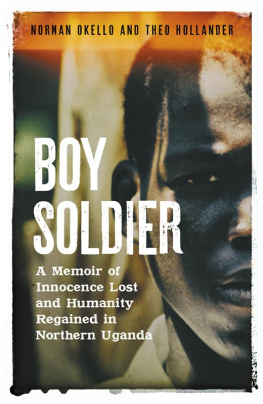

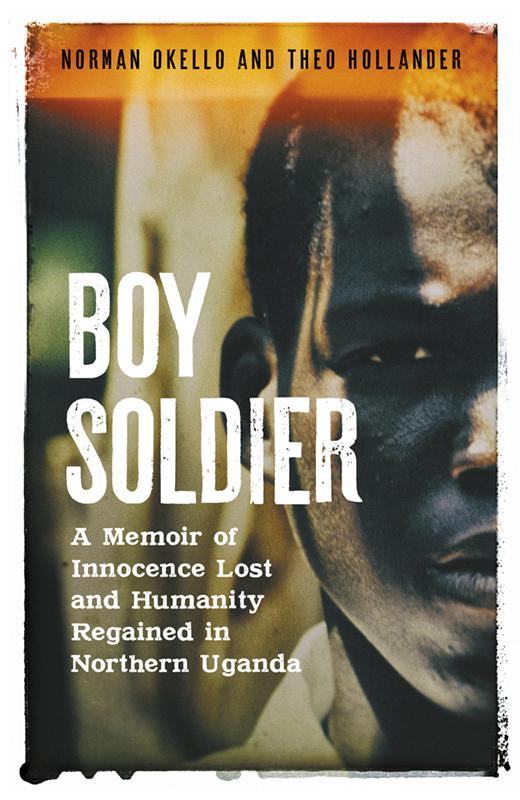

Foreword

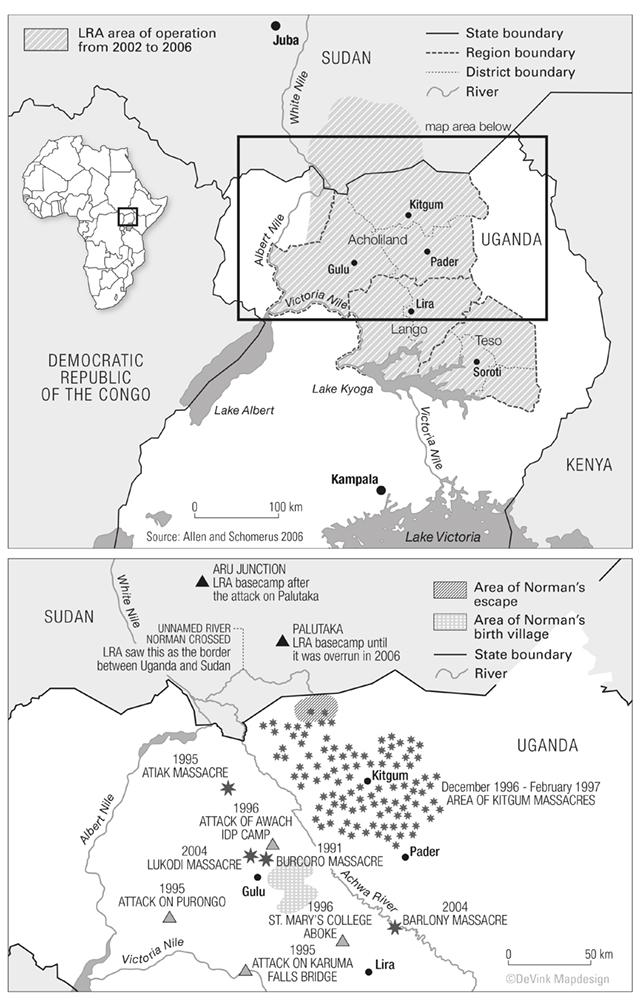

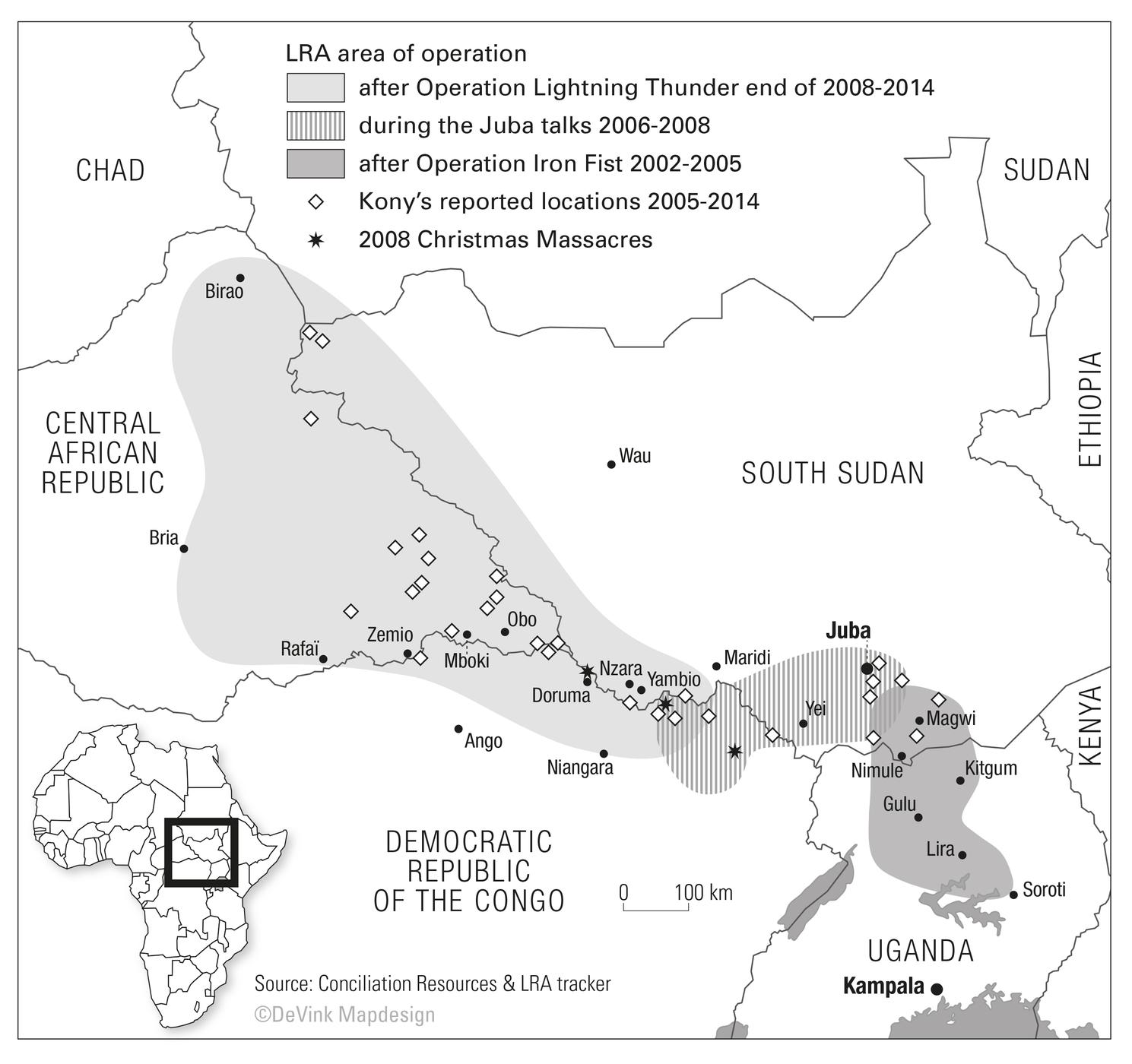

This is Norman Okellos story. On New Years Day in 1995, at the age of twelve, he was abducted from his village in northern Uganda and forced to become a soldier in the Lords Resistance Army (LRA), one of the most brutal guerrilla armies ever to have emerged from Africas troubled history. For decades, the LRA has been led by the charismatic but ruthless Joseph Kony, a man who claims to be Gods spokesperson and a spirit medium, and Normans account of a life of warfare, hardship and horror while serving under him is shocking almost beyond words.

I first met Norman Okello in the last weeks of the Ugandan dry season in March 2007. He was still heavily traumatised. He suffered from severe insomnia and nightmares and he had major trust issues. At times he would appear to behave irrationally. He would often get up in the middle of a conversation and start running as fast as he could, sprinting into the distance until his legs couldnt carry him any further. Norman told me that there were moments when he was engulfed by overwhelming rage, and to avoid lashing out at everything in sight, he needed to expel and exhaust his anger by running. There were dark reservoirs of violence that clouded his soul and he could easily upset and frighten people, which happened many times after his return from the LRA.

But Norman was also one of the kindest people I had ever met. He was enormously generous and had no desire to offend or harm anyone. His kindness was demonstrated in the way he cared for his fellow war victims and the way he treated me. He voluntarily committed himself to improving the lives of former child soldiers and he was always willing to help me out. He had a great sense of humour and I cant count the number of times that we laughed our asses off during long walks or drinks at the local bars. He was a master of gallows humour and self-deprecation.

I was nervous and unsettled before my first interview with Norman it was the first time I had spoken at length with a former child soldier. I had read a substantial amount of literature on the insurgency in northern Uganda, including several accounts of former child soldiers. However, none of this prepared me for Normans revelations. It was not only his story that disturbed me, but also the way he told it. Although his recollections were vivid and animated, his body language suggested that his mind dwelt in a shadowy netherworld. His eyes seemed far away, looking into a past that was way beyond my experience. What I heard were accounts of unimaginable strength and courage but also terrible violence and appalling atrocities. Normans testimony gave voice to the life of a young boy who was forcibly abducted but who tried to cling to his humanity, even though all the odds were stacked against him, and through his words I caught a glimpse of the malignant nature of the LRA.

Norman worked for an organisation called the War Affected Children Association (WACA), and it was through this organisation that I came into contact with him. By May 2007 I had conducted several interviews with him and although by then I had interviewed many former child soldiers, mostly females, Normans story continued to leave the greatest impression on me. It was not so much the narrative itself that distinguished his story from others all the stories that I have heard in northern Uganda easily merit a book it was the way he told it. Norman is a natural storyteller: he has an incredible gift for narrative, capturing so well the telling detail, the arc of events, and the nuances of place, character and emotion.

It was not until April 2008 that Norman overcame his fears and suspicion and finally opened up to me. He began to recount his own role in the horrors that had unfolded: in his narratives, they did was replaced by I did. Later that year, we decided to visit some of the places that featured in his story. We travelled through the central north of Uganda, from Nwoya to Kitgum and from Lamwo to Lira. We crossed the border to present-day South Sudan, visiting Palutaka and Pajok in Eastern Equatoria. The locations helped trigger Normans memories and revive details that otherwise would have been lost.

When I met Norman again in September 2009, he told me he no longer suffered from insomnia and that his traumas were much less severe. The process of writing this book has had a healing effect. As Norman put it himself: Remembering the past helps you to forget.