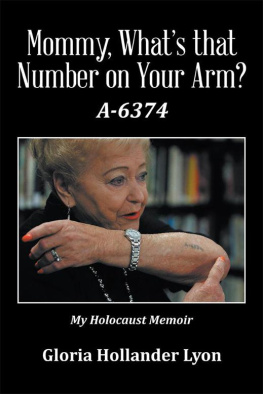

Mommy, Whats that

Number on Your Arm?

A-6374

My Holocaust Memoir

Gloria Hollander Lyon

Copyright 2016 by Gloria Hollander Lyon.

Cover photo courtesy of Paul Chinn, San Francisco Chronicle photographer

Library of Congress Control Number: | 2016901458 |

ISBN: | Hardcover | 978-1-5144-5505-0 |

Softcover | 978-1-5144-5506-7 |

eBook | 978-1-5144-5504-3 |

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Rev. date: 05/18/2016

Xlibris

1-888-795-4274

www.Xlibris.com

536905

CONTENTS

PART IMY NAME IS ZORA,

BUT EVERYBODY CALLS ME HANCI

PART VIAS GLORIA HOLLANDER LYON,

THE WIDE CIRCLE CLOSES

This book has its genesis in the 1950s, when my first son, David, was very small and casually asked me, Mommy, whats that number on your arm? That was when I first realized the importance of recording my painful memories. Writing them down at that time, however, was out of the question, as I tended to break down and cry at the slightest remembrance.

I did my best to explain my tattoo to David, in a language that was comprehensible to a young child. Then later, after my second son, Jonathan, had been born, both my sons began to convey anxiety about the tattoo on my left forearm and to ask difficult questions about my background. So I gradually started to preserve my memories for a time when it would be easier to verbalize them. I definitely did not want my sons to see me cry. They were still too young to hear about the Holocaust, and furthermore, I was not ready to tell them. Those were emotionally difficult years for me. In the decade following the Holocaust, I was still plagued by nightmares and migraines. Eventually, I was able to answer my sons questions but no one elses.

It wasnt until the mid-1970s when a life-altering incident occurred in the research department of a large financial institution where I was an analyst that I found the strength to speak publicly. In a pile of mail that had been routed from desk to desk until it reached mine, I came across a brochure that featured a black Star of David and a red Nazi swastika. It bore the stunning title A ZIONIST HOAX: THE HOLOCAUST NEVER HAPPENED.

I was shaken to the core. Here I was, still alive, and the Holocaust was already being denied. According to the author of the brochure, the Holocaust had never happened. This rude awakening reconfigured the priorities in my life. I asked myself, What am I doing here spending most of my energies on feasibility research for future branch locations, on various internal studies for senior management, and on creating charts, financial indicators, budgetary control, and the like? Then and there, I determined that I must speak out.

The first opportunity came in 1977, when Rabbi Jack Frankel asked me to speak at the first Holocaust commemoration at my synagogue, Congregation Ner Tamid in San Francisco. This first talk was followed by an appearance at Berkeley High School, where the community theater was filled with several thousand young people. The respect of my congregants at the synagogue and, soon after, the rapt attention of the high school students gave me the necessary courage to go on. If my testimony succeeded in this particular high school, it would succeed in other schools , I reasoned.

To date, I have spoken publicly close to a thousand timesin schools, universities, churches, and synagogues. And my words have been recorded on radio and TV and in numerous newspapers, magazines, and books. I always end my eyewitness account with the following message:

Here is my word of warning for all time and for all humanity: Today we talk about racism and often too lightly. The Holocaust, which annihilated the Jewish communities of Europe, epitomized brutal bigotry in its most horrible and catastrophic form. The tragedy cannot be dismissed merely as the brainchild of that madman Hitler. Rather, it was the climax of many centuries of hatred, prejudice, and discrimination against the Jewish people, who had contributed so much to civilization.

In some way, to some degree, it can happen againanywhere, anytime, and to any people of any ethnicity, race, color, or religion unless we are constantly on guard to eradicate hatred, prejudice, and discrimination among all human beings. Even as I speak, genocide is occurring, most notably in Africa.

Every one of us must do our part; we must treat others with respect, kindness, dignity, and compassion. The human cost of racism is too high, and the pain it causes is too deep. That is why the Holocaust must never simply become a dry page in a history book, easy to skip and forget.

In Response to My Mothers Tattoo

A-6374, the number tattooed on my mothers arm, would come to signify her Holocaust experience. It was not limited to her physical and internal battles for survival during the Holocaust. It incorporated the totality of her experiences: the preservation of her own life and humanity, the reunification with what remained of her once tightly knit family, never getting to see her mother again, and the restarting of a new life in Sweden and the United States of America. It signified lifes recontextualization within the new realities of marriage and children, the rebirth of the Jewish homeland Israel, and the continued resurgence of anti-Semitism in bloody Europe. My mother would say, If you have ever been in Auschwitz, you can never completely leave it. Within our family, everything was colored by, shaped by, and a part of my mothers Holocaust experience. This gave me multiple Holocausts to deal with as I grew up.

As far back as I can remember, the stories of forced separation, slave labor, sadistic punishments, escape, and family reunification have always been the source of powerful metaphors in my life. The fantastic stories my mother told me were the stuff of legends, only my mothers stories were truepart of my own history and heritage. For me, growing up included the process of moving from Holocaust as an abstraction to an engulfing nightmare and ultimately as a rich source to draw on.

As I grew, I would revisit my mothers Holocaust experiences with repeating nightmares and new eyes. Maturity brought greater horror, deeper pain, anger, and sadness. At some point, I realized not only metaphorically but also in a very real sense that a part of me survived Auschwitz, just feet away from the crematoria, as my mother was carrying my unfertilized egg within her. The Nazis were trying to murder me along with her. This knowledge was confounding and distressing. My mother made me feel I was precious. Was there really that much evil in the world?

Most of my mothers relatives didnt survive the camps, while almost all the others remained trapped in the USSR. As a child, my grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins were not flesh and blood family members whom I could visit and come to know personally and love. They were pictures frozen under glass. My relatives were, at first, an abstraction to mefaces frozen in time, bare like the bones in Elijahs vision, stripped of the fleshy substance and sinew of their lives. As they emerged from behind the Iron Curtain to live with or near us, I realized that these were my relatives. My nightmares became filled with the horrors I heard, as their new frightful stories meshed with my mothers.

The most fundamental question I asked growing up was based on a story I first heard as a young boy from my mother, a story that continues to profoundly affect me. Astonishingly, Mother had been saved on the way to the gas chamber by the heroic act of a single guard. If that guard in the midst of Auschwitz had the courage to risk his own life and allow her to escape the gas chamber, does it not then become not only imperative but also essential for me, in my relatively safe and free existence, to allow the highest Jewish ethical standards to inform my own decisions and to show the same courage in their implementation?

Next page