The Risk ofSorrow

Conversations with HolocaustSurvivor,

Helen Handler

Valerie Foster

with a Foreword &Afterword by

Helen Handler

Published by Albion-Andalus Books atSmashwords

Boulder, Colorado 2014

The old shall berenewed,

and the new shall be madeholy.

Rabbi Avraham YitzhakKook

Copyright 2014 ValerieFoster and Helen Handler. All rights reserved.

This ebook may not bere-sold or given away. No part of thisbook may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or anyinformation storage or retrieval system, except for brief passagesin connection with a critical review, without permission in writingfrom the publisher:

Albion-Andalus,Inc.

P. O. Box 19852

Boulder, CO80308

www.albionandalus.com

Design and layout byAlbion-Andalus Books

Cover design by SariWisenthal-Shore

Cover photo by PatShannahan for The Arizona Republic

(with an early picture ofHelen Handler layered into the background).

Other photos courtesy ofHelen Handler, Tom and Valerie Foster.

ISBN: 9781311430144

To enter into any profoundrelationship

is to run the risk ofsorrow.

Siddur Hadash

(Helens prayerbook)

Dedicated to the sixmillion

And especially to Helensfamily:

Mother, ReginaAckerman

Brother, NndorAckerman

Brother, MiklsAckerman

Grandfather, WilmosAckerman

Grandmother, EthelAckerman

Aunt, MariaAckerman

Aunt, BertaAckerman

Aunt, CiliAckerman

Contents

Acknowledgements

Valerie wishes tothank Irene Frias, who first set her onthe path to teaching Holocaust literature,as well as Kim Klett, David Dummer, andall her fellow teachers who continue to teach the lessons ofthe Holocaust. She sends out thanks to herstudent, Richelle Pi a, who put her in contact with Mrs.Helen Handler, and to all her students whoembraced Helens words and spirit. She is grateful toNetanel Miles-Ypez, for his sharedcommitment to preserve testimonies of those survivors before they are gone forever. Her husband,Tom, has earned her undying appreciationfor his constant love and patience, as well as thoughtful reading and gentle suggestions. She offerslimitless gratitude to Jenna-MarieWarnecke, Emily Groeber, Dr. Billie Cox, and Dr. David Kader, who came to her aide as thoughtful,expert editors. Finally, she thanks Helenfor the love she showed me, the friendship she offered me, the lessons she taught me, and thetrust she felt in allowing me to peel thelayers of her soul.

Helen wishes toacknowledge her son, Barry, who gave mylife value and a reason to survive, and Rabbi Rick Sherwin, whowatched me go through the sand and come up through the sunshine.She also owes a debt of gratitude to so many, many good friendswho, in their own ways, kept her alive, from the concentrationcamps, to the hospitals, from those in other countries, to those inher Phoenix community today, especially Pat Friedlander, who gaveme love like the daughter I never had. Some friends she knew for amoment, a month, a lifetime, but sees each and every one as Godsway of talking to me.

Preface

Guilty.

I am guilty. For years, asa high school literature teacher, I avoided material about theHolocaust. It was a topic that had always touched a raw nerve in methat went beyond words. I would rather take my students throughDantes Inferno ,which I did, than tackle this deeply disturbing subject in aclassroom setting. I thought I just couldnt handle it. My studentswill learn what they need to from someone else, sometime else, Ireasoned. There are so many other valuable themes and subjects totackle, and oh, so little time.

But eventually, anotherteacher persuaded me to teach Elie Wiesels Night , alittle book that opened floodgates of learning for mystudents and me. We examined the booksliterary elements, but even more, we delved into its layered themeson humanity with all its virtues and failings.

I witnessed that magicaltransformation when literature takes us from the abstract ofmetaphor to getting to the core message, the heart of a piece. Evena few tall, strapping high school boys, who confessed theyd neverread any book in its entirety on their own, were compelled by Wiesels first words to read everychapter. Indeed, my most resistantlearners were moved to new depths of understanding and compassionas they followed young Elies devastating days in a concentrationcamp. Elie, fourteen, so close to their own ages.

I realized that there wasno more important subject that literature offered us.

This led to my developinga major unit of study for my senior writing classes. We went on toread Viktor Frankls Mans Search forMeaning , performed oral readings of othersurvivors journals, and examined relevantfilms and documentaries.

It is difficult to wrapones head around the unfathomable statistics of this chapter in history. But learning of one Ann Frank orlittle Elie brings each of us to a silentcommunion with another human being.

To see high school seniorsbrought to tears of reverence and empathy, and pour their heartsinto essays and discussions to follow, changed my teaching world. Ionly wished I had had the courage to teach this subject muchearlier.

I knew that the greatestimpact for my students would be to meet a survivor, and began towonder if the greater Phoenix area was home to any. Providentially,one of my students informed me that the senior center where shevolunteered had just recently hosted a guest speaker, a Holocaustsurvivor, and perhaps we could have her visit our class. She put mein touch with Helen Handler. I called Helen to invite her to myclass; thus began a conversation and friendship of a lifetime. AsHelen reminds me, the whole world is a survivor. Every person has astory to preserve of this historical event, direct orindirect.

Never, never forget. The story must goon.

ValerieFoster

Foreword

The End of theWar .

It happened so long ago. Ifelt that I had closed the door on these memories forever. Then afew years ago, with the Solidarity trouble, Poland was back in thenews, with the name of a city: Katowice.

To most people, Katowiceis only a foreign word, a name, but not to me. For me it bringsback dormant memories. All I have to do is close my eyes and thereI am once again, walking the streets of Katowice. Before me appearthose wide, shaded boulevards framed on both sides by stately,beautiful old homes that tell a tale of past wealth and pastculture.

At the end of theboulevard I see a huge, gray, smoky building, the railway station.The station it is crowded; it is noisy. Men, women, and childrenare speaking in half a dozen different languages, most of the timebarely understanding each other.

The year is 1945. Ashattered Europe is trying to come to life again. For the last fewyears Poland was the dumping ground for all human rejects. Now theprecious few who stayed alive have to get backto someoneto theirown countries.

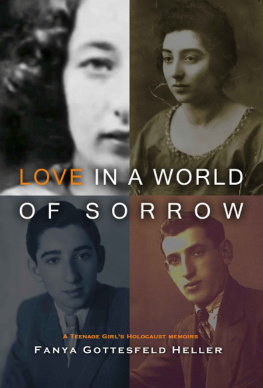

In one corner I see alittle human bundle sleeping, a girl, still a child. She comeshalf-awake now and is aware of all the noise and commotion aroundher. She decides not to open her eyes yet. Shes going to play thegame, her private little game she used to play in the camp. She used to pretend that she would openher eyes and find herself free again. Shehad played the game over and over in the last two years. She lostevery time. Now the nightmare is over, yet she is still afraid to open her eyes. She is afraid tofind herself once more surrounded bybarbed wire.

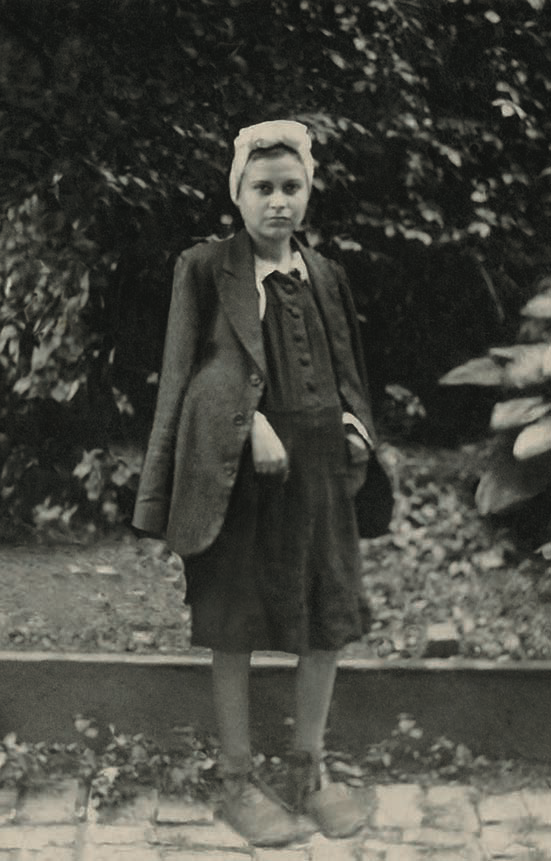

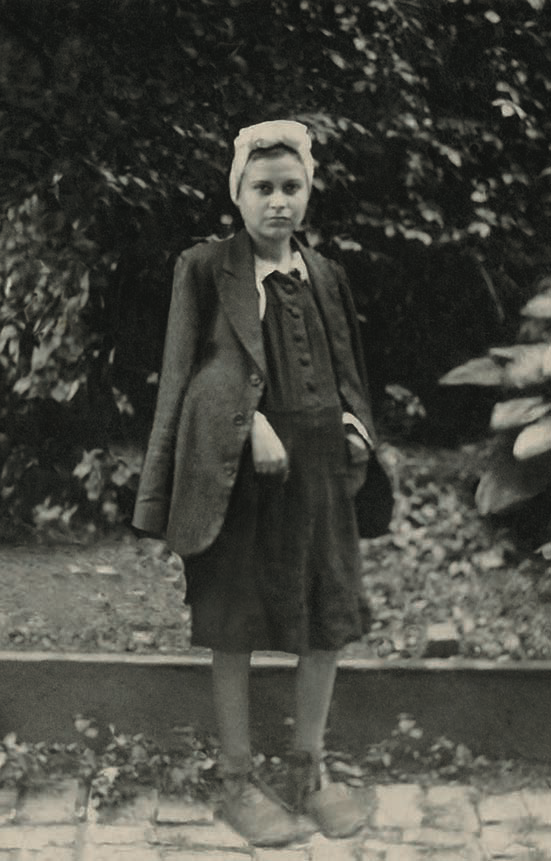

Helen after herliberation.

She wakes up, thenremembers that she got in to town the night before. The train brokedown. They tell her that there would not be another one going outof here for several days. She accepts this fact without emotion;she is used to accepting facts.

Next page