All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Dying earth,

No water, no forest,

Home and love so far.

The night is so dark, the furrow so cold,

How fearfully the stars do flicker!

Burning sun,

How I fear,

How I am ill, oh so tired!

I climb up the rocky slope

And find not rest not peace

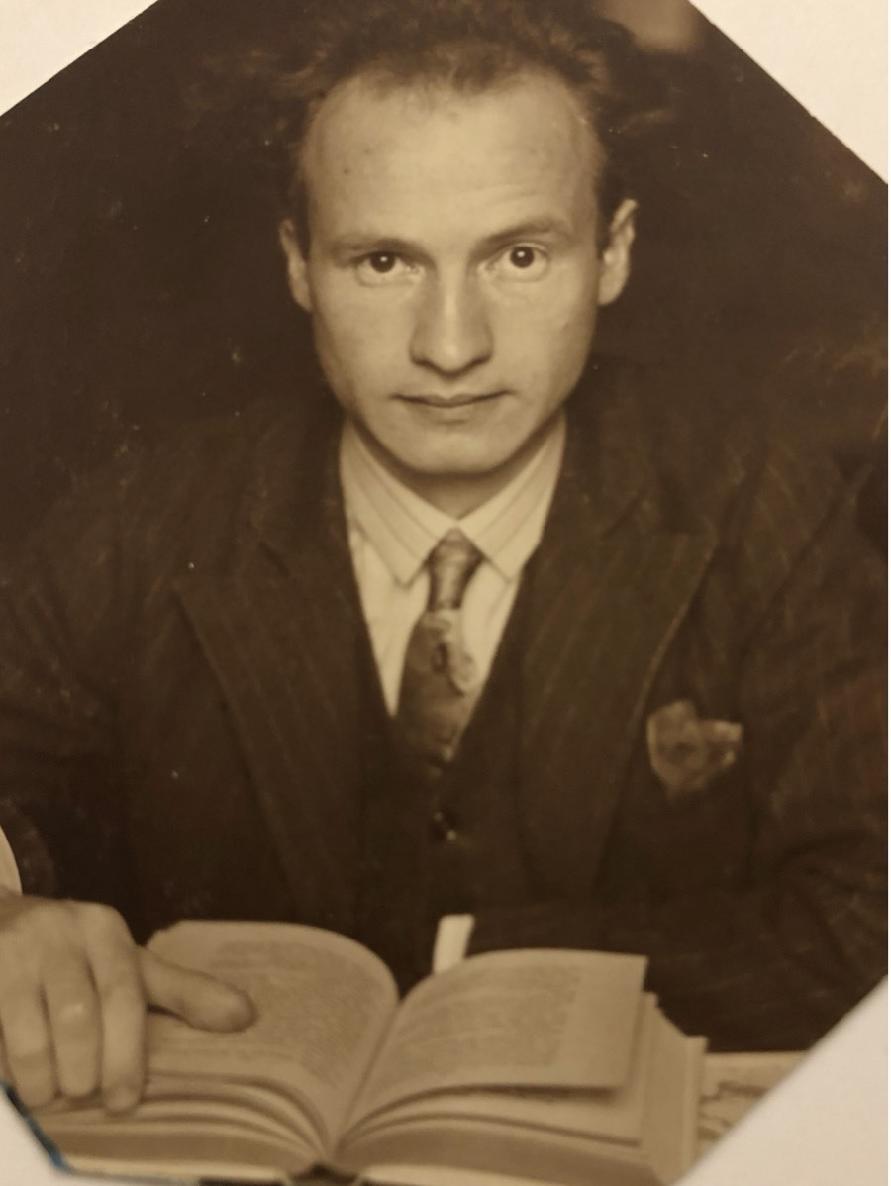

Walter Leopold, September 1943

Introduction

Could German Jews have done more to rebel against the Nazis and resist their deportation to slaughter?

Dr. Walter Leopold faced this question in real time, and in his diary shares his daring version of Jewish resistance. Willing to take his own life rather than to be captured by the Gestapo, he carried a weapon at all times.

Born in 1898 in Ottweiler, Germany, the son of a cantor, Walter grew up in small villages with very few Jews in the southern Rhineland. Sincere about his faith but not Orthodox, he fought in WWI for the German Imperial Army, along with approximately 100,000 Jews, and received an Iron Cross for bravery in the Macedonia campaigns. After the war he attended Heidelberg University, earning his doctorate with the hope of serving in the new Weimar Republic, the first democratic government in German history. His dissertation focuses on the health and welfare of Jews in Palestine, and concludes with the statement that Zionists should not determine the future of the Jews. He, like many assimilated Jews, is Jewish and German. Germany is his home, his passion, his calling.

Like many other young people in that era, he was drawn to radical politics and eventually aligned himself with what he called left-wing socialism. When the Soviet Union was born in 1917, he witnessed the fracturing of the German Socialist Party (SPD). The militant socialist wing formed the German Communist Party (KPD), which failed to lead a revolution at the end of WWI. The SPD was more cautious and participated in the Weimar government. Party politics was intense and bloody throughout the 1920s, with the Socialists and the Communists battling each other. While suffering from draconian war reparations, the Weimar Republic faced extreme economic hardship, including Germanys infamous hyper-inflation. During this post-war chaos, the far right captained by the young Adolph Hitler, groomed and supported by German business and military elites led a failed coup dtat in 1923 (The Beer Hall Putsch). Hitler was arrested and sent to prison for a five-year term but was released after nine months.

Although closely aligned ideologically with the Left, Walter, a keen student of these events, claimed to be completely independent of all parties and political clubs, a stance he considered a badge of honor.

During the 1920s, Walter was unable to find public employment in the Weimar government commensurate to his high-status academic degree, even though that social democratic government was much friendlier to Jews than the pre-war Bismarck monarchy. Instead, he found work within the Jewish community as a director of the Reichenheim Orphanage in Berlin. There he met his future wife, Hilda Blmlein, a pediatric nurse and daughter of a prosperous factory owner in Leipzig, a city with a population of about a half million. By 1930, Walter relocated to Leipzig, married Hilda, and lived in a wing of her parents spacious 10-room apartment.

Leipzig was home to the seventh largest Jewish population in Germany as of 1933 (approximately 12,000). Unlike most German cities it allowed this Jewish community for nearly a hundred years to run its own governing body the Gemeinde. Since the 14th century, at least, Jews had come to Leipzig because it was home to one of the largest trade fairs in Europe. Between 1688 and 1764 municipal records show that more than 80,000 Jews had attended these fairs. By 1866, Jews had been granted equal rights to live within the city and they formed a vibrant community (but not a ghetto) that ran its own affairs. The local government authorized the Gemeinde to raise taxes from Leipzig Jews and to administer its schools, places of worship, and cultural activities. Starting in 1933, the Gemeinde found itself increasingly in the grip of Nazi repression.

Walter became a public official of the Gemeinde and throughout the 1930s he directed plays and other public performances, ran its orphanage and then became an auditor in its tax department. When the roundup of German Jews began in mid-1942, part of his job was to collect the exit taxes from those on the next transport to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, which the Gestapo claimed was a Jewish resettlement camp. As the deportations commenced he was ordered to go to the homes of soon-to-be deported Jews to assess their valuables. Walter urged these families to hide their cash and jewelry to avoid confiscation, but often he found they were too fearful to take the risk.

* * *

Given the Gestapos ironclad control of Jewish life in Nazi Germany, was it actually possible to resist in any meaningful way?

Overt acts of sabotage led to immediate interrogation, torture and then deportation to concentration camps or even summary execution. Nevertheless, Walter believed he could be a disruptive force, a significant obstacle to the Gestapos plans, assuming he could avoid detection and draconian punishment.

He knew the difference between collaboration and resistance, and claimed to see it clearly within the Gemeinde leadership as younger, less politically reliable, leaders rose to power there. What he sees are collaborators who do the Nazis bidding as a means to maintain power and gain favor. To Walter there is always a clear distinction between working from within to disrupt the Nazi machine, no matter how minor the acts, and helping it run more efficiently in pursuit of selfish opportunistic aims.

Through his underground political contacts Walter learned that Theresienstadt was a death camp, or at the very least, the first stop to other camps with ovens. He couldnt bear to watch as his Jewish neighbors meekly arrived at the deportation location, a former school no less, passive, defeated, forlorn. There they were pushed, robbed and beaten by guards who reveled in their brutality and absolute power. No resistance. None at all. Its a work camp. It wont be so bad. We will endure, his Jewish neighbors claimed.