PENGUIN BOOKS

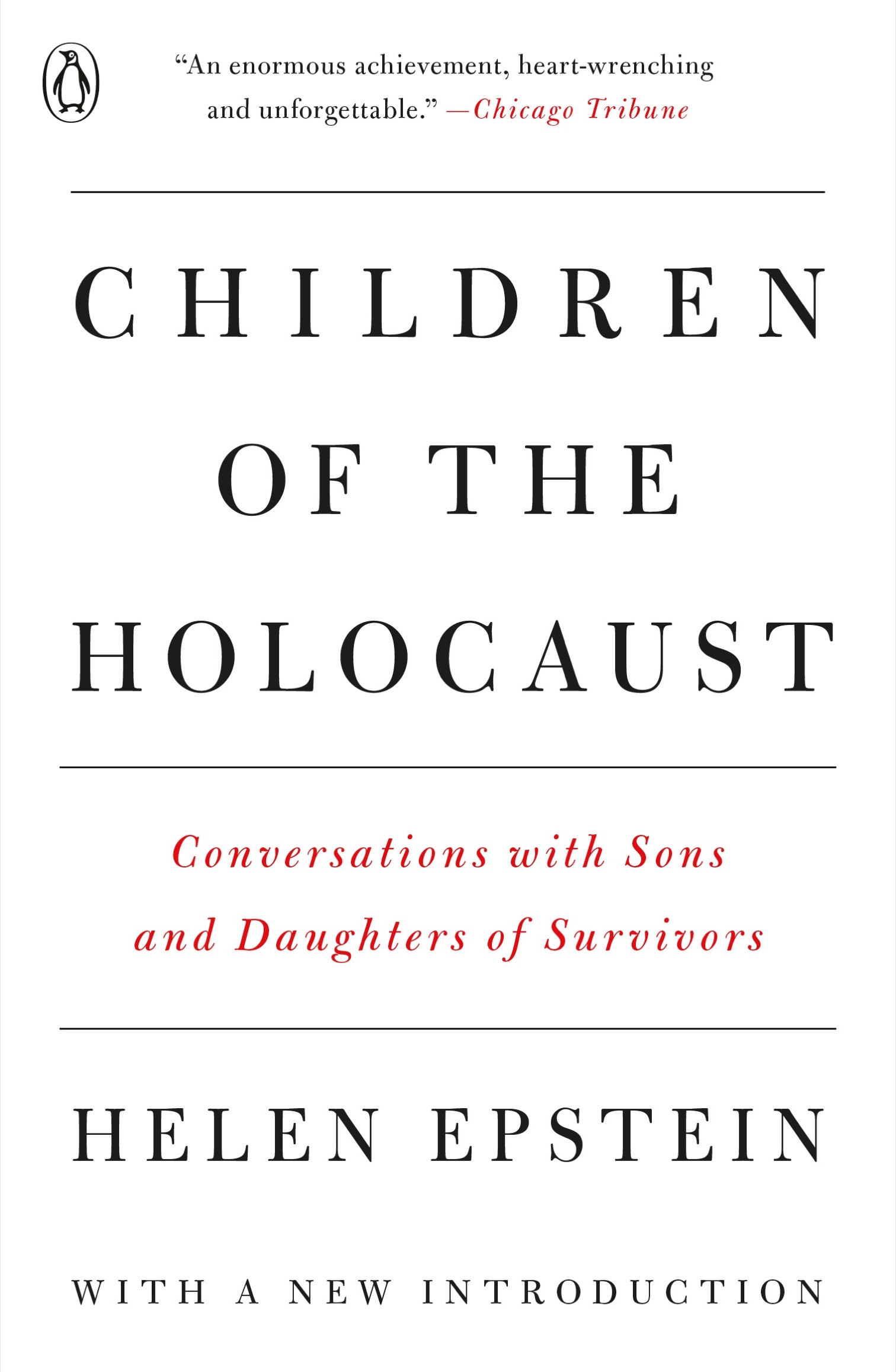

CHILDREN OF THE HOLOCAUST

Helen Epstein is the author, editor, or translator of ten books of nonfiction, including the trilogy Children of the Holocaust, Where She Came From: A Daughters Search for Her Mothers History, and The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma. She lives in Massachusetts.

helenepstein.com

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in the United States of America by G. P. Putnams Sons 1979

Published in Penguin Books 1988

This edition with a new introduction published 2019

Copyright 1979, 2019 by Helen Epstein

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from Hey Jude by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. 1968 Northern Songs Limited. All rights for the United States, Canada, and Mexico controlled and administered by SBK Blackwood Music Inc. under license from ATV Music (Maclen). All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Used by permission.

Ebook ISBN: 9780525507703

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLIC ATION DATA

Epstein, Helen, 1947

Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with sons and daughters of survivors / Helen Epstein

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Putnam, 1979.

Bibliography: p.

ISBN 9780140112849 (paperback)

1. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Psychological aspects.

2. Children of Holocaust survivorsPsychology. I. Title.

D804.3.E67 1988

940.531503924dc19 889606

Cover design: Colin Webber

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

In memory of my father and for my mother

Introduction to the 2019 Edition

T he Polish literary journalist Ryszard Kapuciski wrote, Each piece of reportage has many authors, and it is only thanks to long-established custom that we sign the text with a single name. That was particularly the case with Children of the Holocaust, a collective endeavor that, at times, resembled a virtual consciousness-raising group more than a series of interviews between reporter and source. The result was the first book to explore the psychological aftereffects of genocide in a group that came to be called the Second Generation.

For me and my interlocutors, the experience was extraordinarily powerful. By articulating our private concerns out loud, Children of the Holocaust changed our lives and, hundreds of readers have let me know, the lives of many others. Some read it cover to cover on the day they bought it. Others put it in a special place and were afraid to open it for years. Still others carried it in a bag to be shared only with trusted colleagues and friends.

One of the peculiar features of trauma is that shame perversely attaches to the victim rather than to the perpetrator. An aura of taboo and shame surrounded many families of Nazi victims, particularly in Europe. While a few groups in America, such as the Warsaw Ghetto Resistance Organization, publicly commemorated Jewish heroism as well as martyrdom and created youth groups for their children, most discussion of the Holocaust was not celebratory. Some survivors had the Auschwitz tattoos on their forearms removed; many changed their names and religious affiliation in their new countries. All except the irrevocably damaged focused on the enormous task of rebuilding their lives, the majority in new cultures. Whether they continued to live in eastern or western Europe, under totalitarian or democratic governments, or immigrated to North or South America, Australia or New Zealand, they wished to forget the horror of the war. Few outsiders wished to hear about it.

In the postwar 1950s, neither genocide survivors nor the medical profession knew much about the physiological or psychological aftereffects of massive psychic trauma. The term PTSD had not yet been coined; trauma studies was not yet a discipline; neuroscience was in its infancy. The Cold War followed on the heels of the Second World War and in many countries the murder of Jews all but disappeared from public discourse. Anti-Semites questioned whether the Holocaust had even occurred. Throughout the world, children of Holocaust survivors were encouraged by their teachers and their own parents to blend into their local communities.

I grew up on the multicultural but largely Jewish Upper West Side of Manhattan and attended school with children of domestic and international refugeesblacklisted American Communists and Chinese and Latin American political refugeesnone of whom advertised their traumatic family histories. At a sixth-grade reunion years later, some of my former classmates recalled the Auschwitz tattoo on my mothers forearm and being told by their parents not to stare or ask any questions.

I lived in two cultures. At home, my refugee parents and their friends spoke freely about their wartime experiences, but at school and in the culture at large, the Second World War was almost exclusively about American military prowess. In the 1960s a popular television sitcom, Hogans Heroes, portrayed Nazis as clueless and incompetent. The gap between domestic and public discussion of the war persisted until my college years. In other parts of the world, especially Communist-dominated Europe, it existed for much longer.

Since there was so little public dialogue, I didnt know other members of the Second Generation in New York were thinking about the same issues I was. I did not meet Toby Mostysser, David Szonyi, Anita Norich, and Lucy Steinitz, who published an anthology of essays about the Second Generation in 1975; or Art Spiegelman, who began interviewing his father at that time and drawing what would become the brilliant graphic novel Maus. Second Generation artists and writers Eva Hoffman and Bernice Eisenstein in Canada; Anne Karpf and Lisa Appignanesi in the United Kingdom; the late Nava Semel, Ari Folman, and Savyon Liebrecht in Israel; Irena Klepfisz, Lev Raphael, Sonia Pilcer, Melvin Jules Bukiet, Elizabeth Rosner, and Thane Rosenbaum in the United States; and Henryk Broder and Aliana Brodman in Germany developed their thinking about the legacy of the Holocaust separately.

Like many Jews, I was deeply influenced by the African American civil rights movement of the 1950s, which I understood was as much about self-definition as attaining legal equality in the United States. But it was not until I was a student at Hebrew University in 1967 that I understood for the first time what it taught me about myself. In Jerusalem, I identified what I called a peer group without a sign. Many of my friends there were trilingual, speaking the language of their birthplace; the language of their parents country; then Hebrew or Yiddish. Jorge from So Paulo, for example, spoke Hungarian as well as Portuguese and English; Samy Szlingerbaum from Brussels spoke French, Yiddish, and Polish. Some of my peers had been born in Displaced Persons camps. Their parents had been resistance fighters or concentration camp or labor camp inmates. Or they had hidden for years in attics or holes in the ground or lived in the open with false papers. All had felt the presence of what they called the war. Our conversations laid the early foundations for this book.