PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2020 by the Franci Rabinek Epstein Estate

Afterword copyright 2020 by Helen Epstein

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following:

: Photo courtesy of Ronnie Golz

: Photo courtesy of Doron Leitner

All other photos courtesy of Helen Epstein

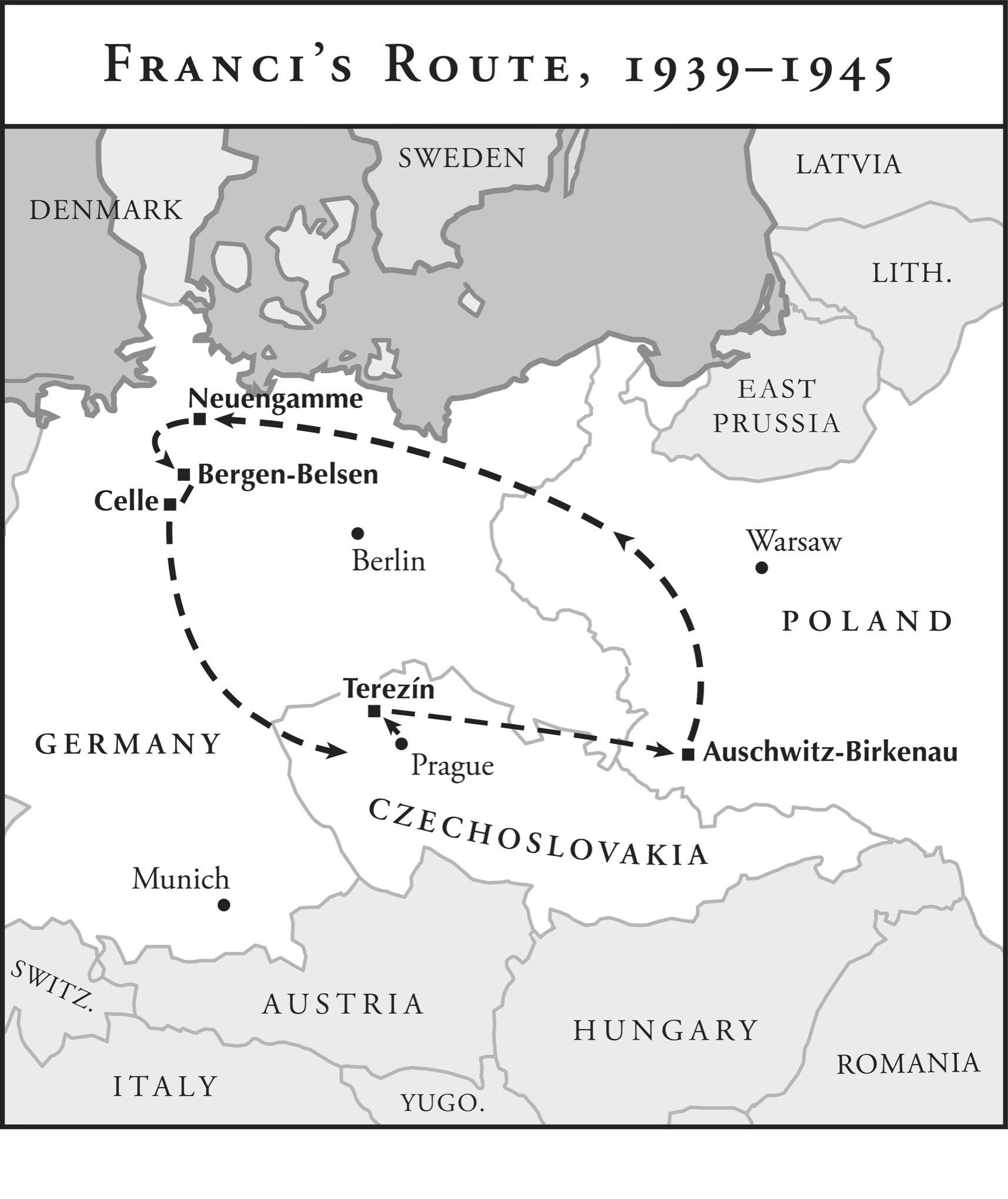

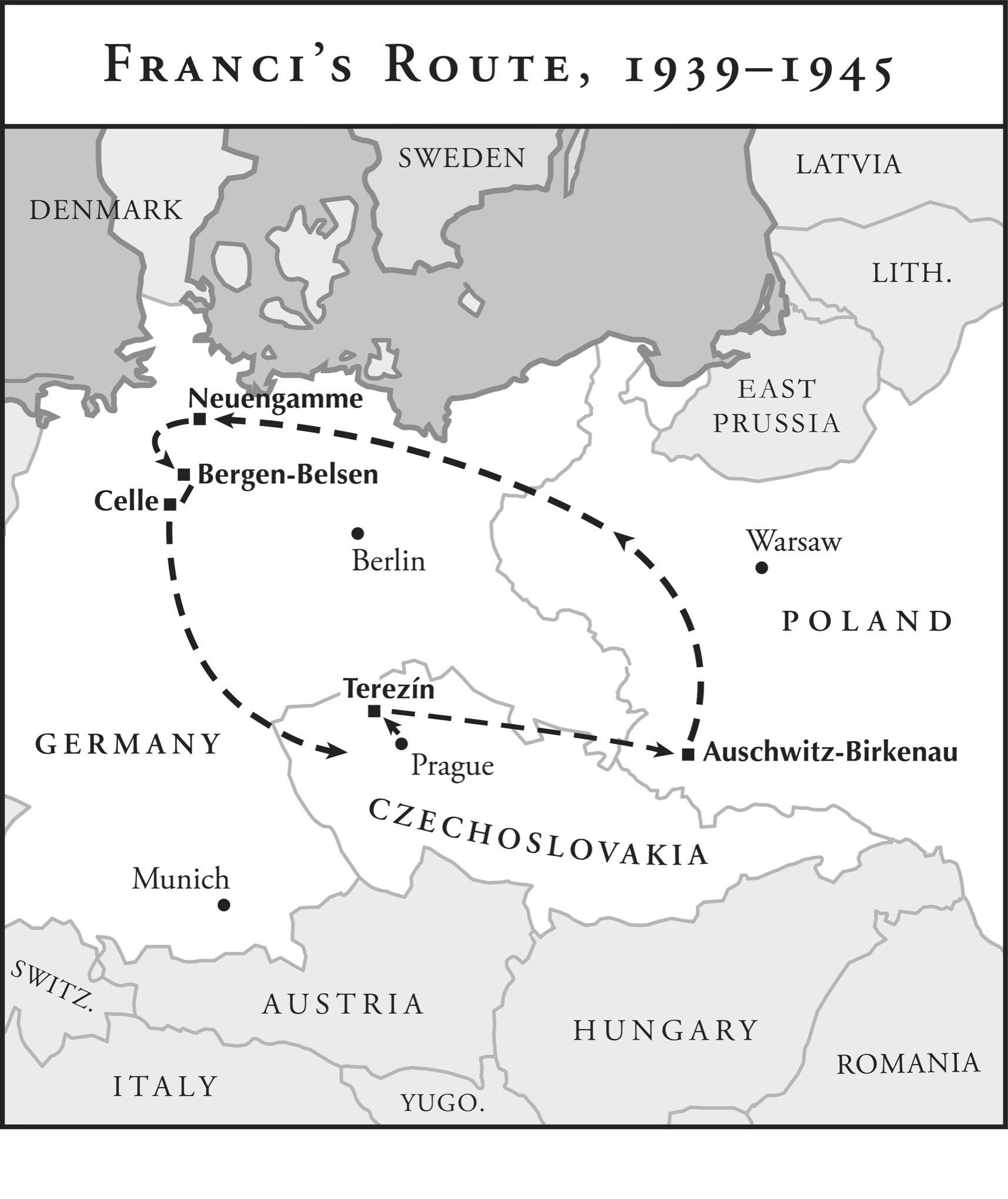

Map by Virginia Norey

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Epstein, Franci, author. | Epstein, Helen, 1947

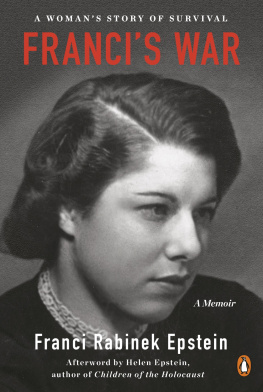

Title: Francis war : a womans story of survival / Franci Rabinek Epstein ; afterword by Helen Epstein.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, [2020] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019039140 (print) | LCCN 2019039141 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143135579 (paperback) | ISBN 9780525507222 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Epstein, Franci. | CzechoslovakiaHistory1938-1945. | Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)CzechoslovakiaPrague. | Fashion designersCzechoslovakiaPragueBiography. | Theresienstadt (Concentration camp) | Birkenau (Concentration camp) | Holocaust survivorsBiography. | JewsNew York (State)New YorkBiography.

Classification: LCC DB2211.E67 A3 2020 (print) | LCC DB2211.E67 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/18092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019039140

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019039141

Cover design: Roseanne Serra

Cover photograph: Epstein Family Archive

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r1

To Helen, Tommy, and David

In memory of their grandparents

CONTENTS

1

It was a hot day in the first week of September 1942, and the Industrial Palace of Prague was teeming with people. Most were lying or sitting on the loose straw on the floor; others were wandering around in a stunned daze. Gone were the shiny displays of Czechoslovak industry that had given the place the air of a happy carnival.

I had often come to the Industrial Palace when I was a child and my fathers electro-technical firm, Korlek & Rabinek, had a booth. It had always been a treat. I returned home with free samples, balloons, and stacks of glossy catalogs. This time I would not return home because the Industrial Palace had been converted to the assembly point for the deportation of undesirables, i.e., Jews, by edict of the Nuremberg race laws.

None of us should have been surprised. The trap had been closing for three years by then, but the systematic humiliation and brainwashing had been gradual and only partially successful. Our humanity was still intact. Our situation had somehow not fully registered until now. It was quite a shock to be suddenly treated like so much cattle.

I was twenty-two and lying with my head in my mothers lap in a sort of stupor. I had just had a tonsillectomy. I had not eaten for a few days and was having trouble breathing the air that was filled with straw dust. My mother kept stroking my hair and trying to make me drink a little water. My father was walking around from one acquaintance to another, hoping to find out what was in store for us. Groups of SS men were storming in and out, yelling orders and rounding up groups of Jewish men to clean the latrines. They made a point of picking out the most distinguished-looking older men in the crowd, the men wearing glasses. My father was one of them.

When they told me in the hospital that my parents and I had been called up for a transport, the nurse, who was a friend of ours, said We can get you out of it because of the surgery. I thought this over for a few minutes and then said Im not letting them go alone. Theyre too old and they dont have anybody else. My mother was sixty and my father was sixty-five. I couldnt visualize those two people going alone anywhere. And there was a little egotistical motivation too. My husband was already gone. I would have been left all alone. Besides, by September 1942 I was so fed up with all the restrictions in Prague that I thought any change of scene would be a relief, no matter what was waiting on the other end. I was always like that, unfortunately.

2

Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, a bit over two weeks after I turned nineteen. My interest in politics was nonexistent, and I was only vaguely aware that all four of my grandparents were Jewish. A year earlier, I had become the owner of my mothers haute couture business. I was carefree, slightly spoiled, and mainly interested in dancing, my business, flirting, and skiing, in that order.

My father, Emil Rabinek, was born a Jew in Vienna in 1878. He was the youngest son in a family of Austrian civil servants and a firm believer in assimilation. At the age of twenty, he had converted to Catholicism in order to circumvent the numerus claususthe Jewish quotaat the University of Berlin. Emil Rabinek had fought with the Austrian army during the First World War without much enthusiasm, and welcomed the formation of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. He had lived in Prague for many years. While he remainedemotionally and culturallyan Austrian, he saw the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic as a new experiment in social democracy, a sort of Switzerland in the heart of Europe with equal rights for all minorities. He chose to be a Czechoslovak citizen.

The next twenty years justified his choice. My father lived as a member of the German-speaking community of Prague, patronizing German clubs, theaters, and concert halls. One of his favorite statements was I am a Czechoslovak citizen of German nationality. He never learned proper Czech. Our extensive library was almost entirely German, with translations from French, English, and Russian literature. He led me to admire everything German or, at least, filtered through the German language. There was not one Czech book in the house until I was in my teens and began to buy them for myself.

Though my father had had plenty of warning about Nazism, he dismissed the news that came from Germany as propaganda. He believed in German decency, justice, honor, and civilization. He was also absolutely certain that Czechoslovakia was a strong country, its sovereignty guaranteed by its French and British allies. Not even the occupation of Austria in March 1938 had shaken his convictions, and he considered his cousins who had fled Vienna to be cowards. His eldest sister, Gisela Rabinek Kremer, and some of her children had remained there. That gave him further evidence that it was a mistake to panic and run.

There were, in addition, financial considerations. In February 1920, when I was born, my father had been a rich manco-owner of a shipyard and an electro-technical wholesale house. Following the American Crash of 1929 and the depression years, his wealth had shrunk. We still had our beautiful apartment, with all its books and paintings, and were living very comfortably. But by the time the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia, our income came mostly from my mothers and my