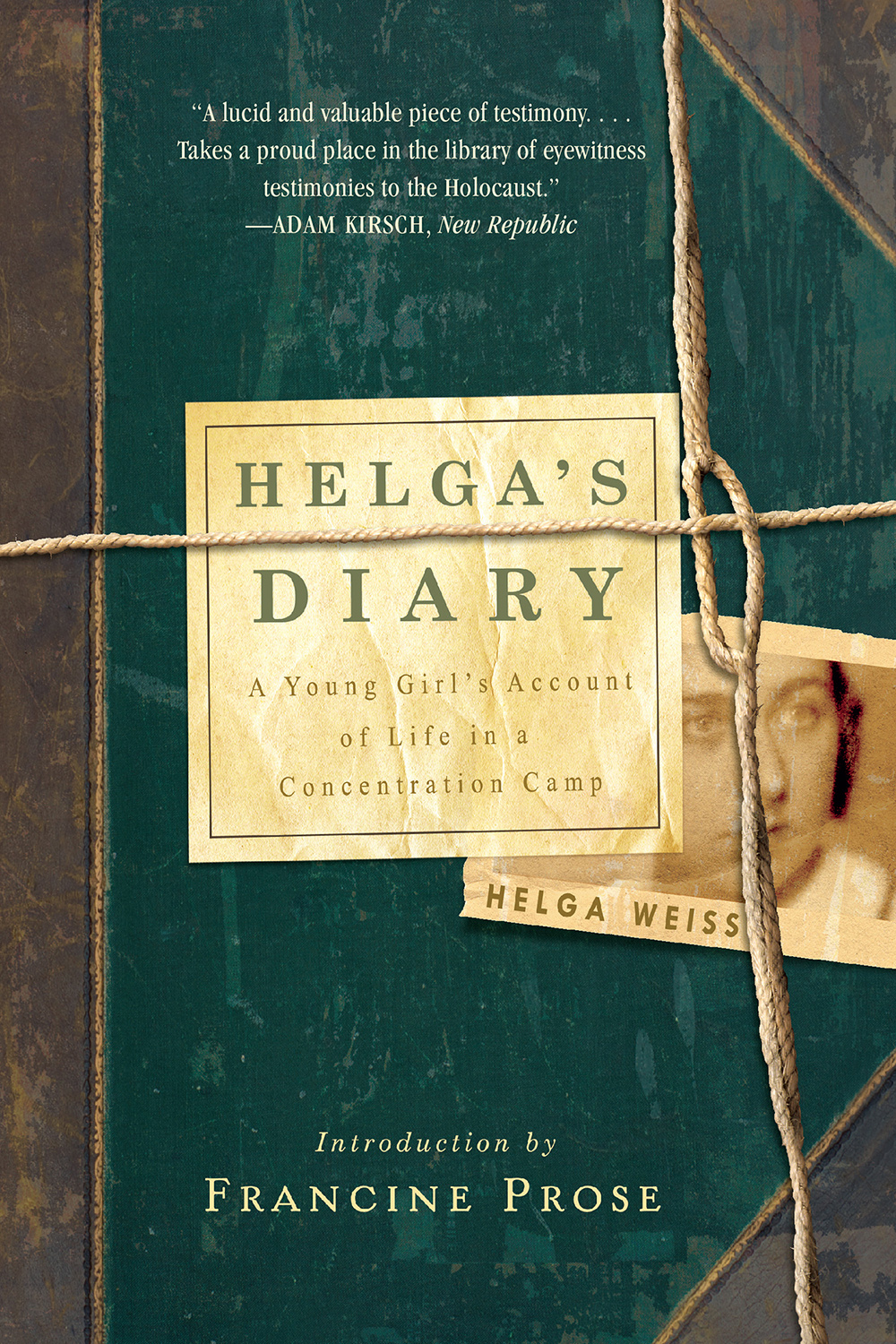

HELGAS DIARY

A YOUNG GIRLS ACCOUNT OF LIFE IN A CONCENTRATION CAMP

Helga Weiss

TRANSLATED BY NEIL BERMEL

INTRODUCTION BY FRANCINE PROSE

To my granddaughters, Dominika, Natlie, and Sarah, and to all young people, in the hope that they will keep the past alive in their memories, and that they will never experience for themselves what my generation has had to live through

CONTENTS

I n The Lost , Daniel Mendelsohns powerful book about his search to discover the fate of six family members killed in the Holocaust, the author recalls a conversation with the mother of the novelist Louis Begley. Having impressed a listener with the amazing story of her escape from the Nazis, Mrs. Begley remarks, If you didnt have an amazing story, you didnt survive.

She was right. The fortunate ones who survived the Nazi genocide had amazing stories. But the less fortunate ones, the ones who didnt survive, also had amazing stories. In a sense, the perpetrators of the mass murder had amazing stories. More than half a century later it still seems amazing (just as it still should amaze us) that such a thing could have happened: that millions of innocent men, women, and children could have been murdered by the Nazis remarkably efficient killing system, in broad daylight and with the full knowledge of so many. The further these horrors recede into history, the fewer the living witnesses who remain to provide us with firsthand accounts, the more importantthe more essentialit is for those amazing stories to continue to be told.

Helgas Diary also tells an amazing story, one that has never been told quite this way before. Helga Weisss narrative begins in 1938, in Prague, just before the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. In the innocent, straightforward voice of the bright, middle-class schoolgirl she was, Helga describes the events that followed the Nazi occupation. As in the other countries that came under German rule, a series of increasingly harsh and punitive laws were passed, designed to demoralize, humiliate, and make life impossible for Jewish families like Helgas. First playgrounds, movies, and parks were declared off limits. Ultimately these restrictions began to seem almost inconsequential compared to those that would follow; eventually Helga was forbidden to attend the state school, which until then she had loved.

Helga accepts the changes, the way a child does, the way the adults around her are forced to do. She goes to an improvised Jewish school and spends the summer in hot, dusty Prague, because Jews are forbidden to travel beyond a short distance from their homes. She makes new friends, meets other children with whom she goes to the Jewish playground. They sew yellow stars onto their clothing and try to wear them proudly, so as not to let the occupiers think that their brave spirits have been broken.

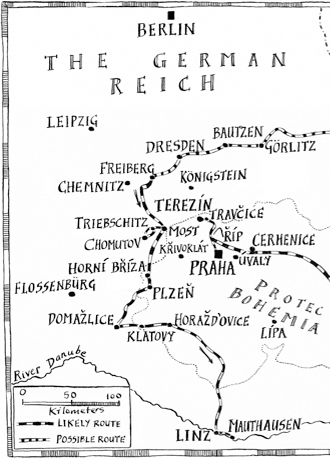

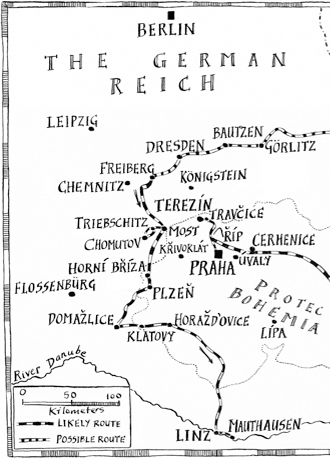

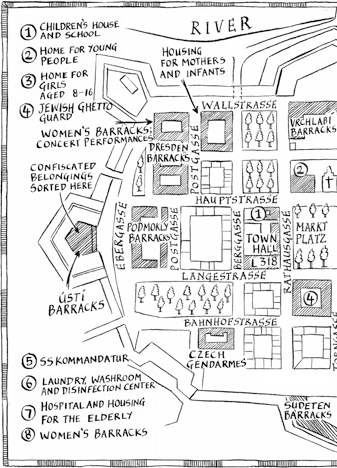

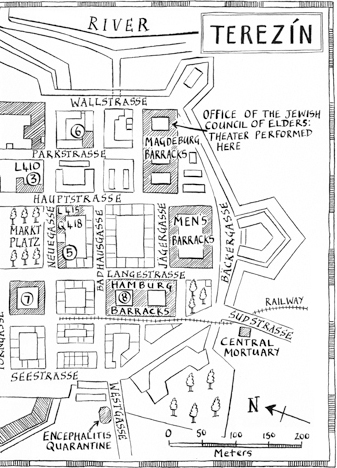

Late in 1941, as Helga describes it, the Jews begin to hear rumors about transports that will relocate them somewhere... but where? There are elaborate preparations for departure, and in December 1941 Helga and her parents are taken to Pragues Trade Fair Palace and from there to the Terezn concentration camp, not far from the city.

What makes Helgas diary so interesting is the sensibility of the girl she was at the time and the girl she is remembering in the sections she wrote later: a feisty young person who could very rapidly and sensibly adapt to any change, however dramatic or drastic. From her early years, she seemed to want, and to have a gift for establishing, a sense of normalcy and order; she clearly believed in the importance of remaining optimistic and of making the best of a badin this case, a very badsituation.

Whats startling, throughout, is the resilience with which her buoyant spirit keeps bobbing up past the hardships, indignities, and cruelties that are part and parcel of the new routines imposed on her by the changing laws of her captors and the whims of her guards.

In any event, she writes of Terezn, theres no reason for crying. Maybe because were imprisoned, because we cant go to the cinema, the theatre or even on walks like other children? Quite the opposite. Thats exactly why we have to be cheerful. No one ever died for the lack of a cinema or theatre. You can live in overcrowded hostels... on bunks with fleas and bedbugs. Its rather worse without food, but even a bit of hunger can be tolerated.... They want to destroy us, thats obvious, but we wont give in (94).

Whatever happens, its Helgas life, and she is determined to live it. One cant help feeling that her talent for finding solutions and resisting despair, as well as the joy she took in small victories, must have in some way contributed to her survival. Likewise, the highly unusual and fortunate fact that she was able to stay with her mother throughout their captivity and in their horrific odyssey from camp to camp strengthened both her resolve and her will; there was nearby, at every point, someone she loved and who loved her, someone beside herself to live for and for whom it was necessary to remain strong.

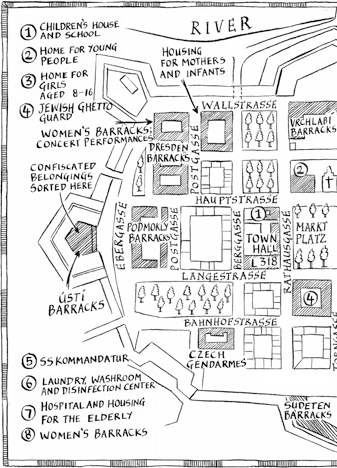

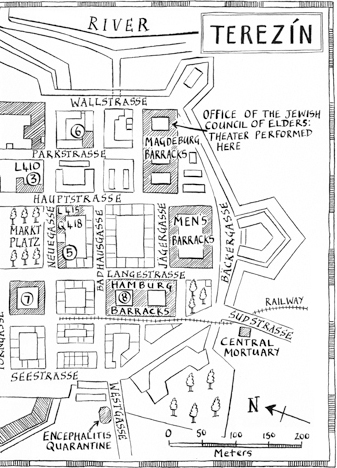

The irony is that this girl so determined, despite everything, to lead a convincing semblance of a normal life was sent to Terezn, the camp that was designed to fool the world into thinking that the Jews were leading quasi-normal lives, that they were being treated in a humanitarian way and with all the courtesies appropriate for detainees in transit to a new population center. In preparation for periodic visits from the Red Cross, efforts were made to demonstrate that the prisoners were healthy, well nourished, clean, and well cared for.

At the museum in Terezn, one can still see heartbreaking films of childrens choruses and classes; there were holiday parties, classical music, theaters, opera performances, a garden. Helga describes a lecture on Rembrandt with illustrative slides and a cultural evening at which the poems of Franois Villon are recited. A childrens playground was built, and Helgas mother was able to make small amounts of money working as a seamstress.

There is even a shop that sells dishes, clothing, suitcases, sheets, perfume, and groceriesoften, articles that have been stolen from the prisoners themselves. It does look like a real town here now, but I simply dont understand what they mean by doing this. If the rooms serving as shops were freed up for people to live in, it would definitely be more useful. On the one hand, theyre sending transports away from here while on the other theyre playing games like this (106).

For all its surface simplicity, Helgas diary provides a penetrating and disturbing description of how the subterfuge of Terezn was orchestrated. Overnight, apparently in advance of some official visit, the prison ghetto was turned into a spa town. Street signs were put up. The school that had served as the hospital was converted back into a school. The ill patients were taken away, and the whole building was painted, scrubbed, school desks were brought in... It really does look beautiful, like a real school, except its got no pupils or teachers. However, this drawback was fixed quite simply: a small sign announcing FerienHolidays (123). Leaders selected from the community tried to ameliorate the conditions of the prisoners and to protect the children; but, however noble, their efforts were no match for the devious and evil machinations of their captors.

Next page