D aughters of Absence

Transforming a Legacy of Loss

Mindy Weisel, Editor

Dream of Things

Downers Grove Illinois USA

" Who can return the violated honor of the self? I cannot claim that art is all powerful magic, or pure faith, but one virtue cannot be denied it: its loyalty to the individual, its devotion to his suffering and fears, and the bit of light which occasionally sparkles within him

Aharon Appelfeld,

Beyond Despair

" Sensitivity to separation, feelings of mourning and guilt, the desire to protect their parents and suffering people in gener al, are common threads running through the fabric of the lives of survivors children. They share feelings of excessive anxiety, bereavement, over- expectation and over-protection.

Dina Wardi,

Memorial Candles

Contents

The Leaving

Gently, tenderly

disengaging

branches barely aware,

foliage in formation

creating

an array of colors

clinging , proudly poised,

beneath lush blankets

bountiful layers of life

Spring's seedling, Summer's glorious gift

tended , nurtured,

defying Nature's formidable decree.

I do not wish to diminish

I long to prolong

seasons ,

detain changes,

delay

the leaving

Dassie Schreiber

October, 1994

Acknowledgments

On behalf of all the contributors to this book, I would like to thank Kathleen Hughes for her great belief in this project and her tireless efforts on its behalf.

A special thanks to Mike OMary for his vision and expertise in publishing a new edition of this book in 2012 and continuing its message that nothing can wipe out the human spirit.

To all our dear family and friends, and those lost to us, may this book always serve as a reminder of the great m iracle and beauty that is life.

Preface : M emorial Candles - Beauty as Consolation by Mindy Weisel

Grandmother Bella Deutsch

To my grandmothers,

Bella Weiszman Deutsch and Mindle Basch Deutsch

(died in Auschwitz 1944)

To the memory of my mother,

Lili Deutsch (1922 - 1994)

To the future of my daughters,

Carolyn, Jessica, and Ariane

In memory of Sauci Churchill and Bernice Fishman, and w ith deepest t hanks and love to Lois Adelson , Roz Barak, Dita Deutsch, Beverly Deutsch, Tobee Weisel, Phyllis Greenberger, Jill Indyk , Ging er Pinchot, and Nancy Sheffner .

D o we ever get used to the feelings of loss? Time sup posedly heals all wounds. Does it really? Or do we take that time and take that loss and turn it into something else, something that takes the shape and the form of our loss ? Is this perhaps the source of the deepest art? Is it the art that actually gives our lives meaning? There are clearly feel ings that are beyond comprehension. It is these feelings that are put into the music, poetry, painting, photography, prose, and theater that enrich our lives, and that are addressed in this book. The women in Daughters of Absence all have one thing in com mon: as daughters of Holocaust survivors they have found a strong voice through their work. For these creative women, their work has been both life force and life saver.

I am one of the daughters. My parents were both sur vivors of Auschwitz. My parents were first cousinstheir fathers were brothers. My father found my mother near death, in a hospital near the camps, nursed her back to health, and married her. I was one of the first children born in Bergen-Belsen, Germanyonce a concentration camp turned into a displaced persons camp after the war. My life was about trying to be everything to my parents . Like the oth ers in this book, I thought the only meaning my life could possibly have was to fill my parents lives with beauty, love, hope, joy, nachas . I, like the others, tried desperately to erase the sadness we inherited. It couldnt be erased. I, like the oth ers, absorbed it. I, like the others, took on the sadness as my own.

Beauty, the loss of it, is what my mother grieved for her entire life. Beauty also was the one thing that could give her momentary pleasure. Beauty in a fresh flower, a crisp winter day, a fresh cotton sheet, a bowl of cherries....

My mother, Lili Deutsch, was one of eleven children. She was raised in an elegant Hungarian home near Budapest. Her parents owned the local bakery. I was raised hearing stories about my grandmother, whom my mother magnificently, through her stories, kept very much alive for me. My grand mother, my beautiful, generous grandmother, who would feed the poor at the back door of the bakery, early in the morning, before the others got up. My beautiful grandmother who kept a beautiful home. A home that my mother tried to recreate for us in America, with her love of crystal, china, fine linens, needlepoint, and fresh flowers.

All things beautiful. I cant, to this day, pass a rosebush without stopping to inhale its fragranceto pay tribute to my mothers love of roses.

My mother was the only one of her sisters who survived the war. She watched her sisters and her parents die in the gas chambers. I only learned, after my mother died in 994, how she survived Auschwitz. I was always too afraid to ask, as I was too afraid of the answer. She survived, I learned, because of her rare blood type, which the Nazis experimented with, thus allowing her an extra measure of soup. This experiment and the soup were a daily occurrence for one year of her life. Her twenty-first year.

Like most survivors daughters, while I was growing up, and even well into my twenties, I didnt know how I really felt about anything. I didnt have my own feelings. I knew how my parents felt. I was not allowed the normal range of emotions. If I was sad or anxious, it made them sad and anxious. And, after all, what was there for me to be sad about anyway? I had not been in Auschwitz. I did not know what it was to be cold, hun gry, or devastated. All my feelings not related to Auschwitz were naarish (foolish). How could any feeling measure up to those one lived with after surviving the camps? So, like so many oth ers with my background, I buried my feelings. Till I could no longer. That is when my work took on a life of its own.

The question that haunts me to this day is, how is one capable of happiness after such devastation and tragedy as my parents endured? And yet, they did know happiness. They knew the pleasure of children, of work, and a full life. But it was difficult for me to understand how one could live and be happy. How could I be happy, knowing what my parents had endured? After what they lost and lived through?

My parents, however, insisted not only on my well-being but on my happiness. To be a good daughter was to be a happy one. Always being understanding, never complaining , and always being there for them. There is nothing I wanted more than to be that good and happy daughter.

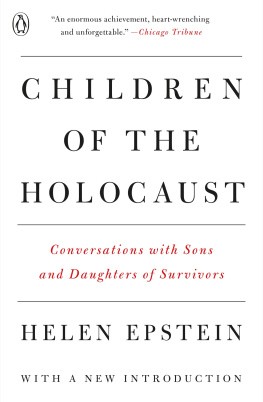

In the beginning of my life as a painter, I was, I suppose, what psychologist Dina Wardi , calls a memorial candle. She claims in her book, Memorial Candles: Children of the Holocaust , that in a survivors home, there is a child in the family who becomes the link among past, present, and future. That child grows up feeling responsible for inter-generational continuity, the one who bears the burden for translating the emotional world of the parents into some kind of coherence.

Only in my studio, while painting, was my authentic voice disclosed to me. Alone in my studio, I was free to feel whatever I needed to feel. I could play music and dance to it while I worked, or weep deeply at lifes injusticesnot wor rying that my tears would upset anyone. They were my tears and my joy. The desire was to put these feelings into my work. Ultimately, alone in my studio, painting became a form of prayer, a form of dance, of song, of life itself. A life that had a desire to hold onto the moment as well as to memory, to expe rience both past and present, and to emotions longing to be released.

Next page