Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

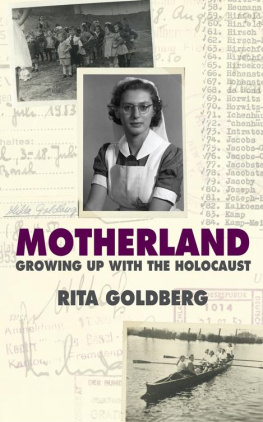

MOTHERLAND

Fern Schumer Chapman a former reporter for the Chicago Tribune and Forbes, has taught at Northwestern Universitys Medill School of Journalism and written for The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Fortune, U.S. Nerws & World Report, and many other publications. Visit the authorsWeb site at http://www.motherland.ws.

For my mother

Like those old pear-shaped Russian dolls that open

at the middle to reveal another and another,

down to the pea-sized, irreducible minim,

may we carry our mothers forth in our bellies.

May we, borne onward by our daughters,

ride in the Envelope of Almost-Infinity,

that chain letter good for the next twenty-five

thousand days of their lives.

MAXINE KUMIN

Prologue

I never thought of my mother as a Holocaust survivor. She was one of the lucky ones. She had been spared, had never faced the horrors of the Nazi death camps.Yet, when she was only twelve, she lost everything but life itself: her home, her family, her language, her loyalties, her identity.

Though she was not scarred with a number, she was a kind of survivor. Like a bewildered animal, a member of an endangered species ripped from its habitat to avoid certain extinction, she had to re-create a life outside her original landscape and context. Uprooted, displaced, and spiritually homeless, she was left alone to bear her imprisoning memory, the unresolvable grief, and the full pain of surviving.

In 1938, my grandparents sent their daughter to America, all by herself, with little more than her clothes. She traveled on the German ship Deutschland to Ellis Island and then by train to her new home in Chicago, where an aunt and uncle had sponsored and agreed to raise her. She was one of thousands of Jewish children from Nazi-occupied countries who became refugees, traveling to any country that would accept themEngland, Sweden, Turkey, South Africa, Argentina, Canada, the United States. After 1938, most rode Kindertransport trains to Great Britain. Parliament had granted entry to ten thousand children between the ages of three and seventeen, once their families paid a fee of $250 each. All the children were sent without parents or families, on trains so crowded that smaller children squeezed into the luggage racks above the seats.

These young fugitives from war are called escapees. An ironic notion, since no one escapes the grip of a homeland, the first ground etched in childhood and memory. No one evades the influence and stamp of a mother who, absent or present, imprints an identity onto her child. No one escapes the motherland. Not my mother. Not me.

Her story, and mine, is about the half-life of the Holocaust and the emotional legacy of an escapee. But there is much more. It is a complicated terrain of pain and love, expectation and disappointment, past and present. Ours is the story of the land all mothers and daughters inhabit.

Here, a daughter cannot see the whole landscape; none of us really knows our mother, or for that matter, our parents. My view was particularly narrow. My mother never wanted me to know anything of her former self, so she restricted what I knew of her present self.

What I could see is that immigration and loss had ripped a fault line in her life. Suddenly transported to a new land, my mother lost herself. Her past blurred; over time, it was buried, becoming a hidden layer of her self, a stratum of a land and a life that she tried to deny ever existed. In years of digging, I managed to excavate only bits of this; my private archeology unearthed too few pieces to construct a past.When pressed about her childhood, she offered small, detached sketches that seemed to tell someone elses story. My mother presented herself as nearly tribeless, without a history, a supporting cast, even a nickname.

This was so even though my mothers older sister had preceded her in leaving Germany. A Chicago family adopted my aunt a year before my mother arrived in Chicago; despite their geographic proximity and the profound loss that might have united them, they spoke infrequently. Reared in separate homes, by families who made no effort to bring them together, the sisters became distant. When they talkedalmost always in Englishthey were mindful of staying in the present. I suspect they limited their contact because each reminded the other of all that was lost. Consequently, I rarely observed my mother in the role of sister, and never saw her as someones daughter, cousin, or niece. She was always just my mother.

Hard as she tried to forget her former life, to shed the before, it echoed in the present. My mother was like an amputee who still feels her toes. Though she made herself into someone else, small things betrayed her. I remember her hunching over her checkbook, softly muttering math in a strange tongueGermanSechs plus acht ist vierzehn. Sometimes, when I walked past the bathroom while she was taking a bath, I would hear her repeating, over and over, words that began with a w: witch, walk, work. She was trying to master its sound, to rub out the v, the last vestige of her German accent. It was her stain.

Each time I overheard her this way, I was struck by the fact that she had another self, a full yet unimaginable life folded into her being. Strangely, it was the parts I couldnt see that had formed me. I became defined not by what I knew, but by what I didnt know.

Identity is derived from self, family, place, and past. For me, most of those elements have been unknowable and my mother has been, in many ways, unreachable. All my life, Ive longed for her, for facts, a lineage, a narrative stream flowing before me, within me, and beyond me.

Chapter 1

The plane blazes toward the breaking horizon, though my mother still isnt convinced she wants to go on this trip. Sitting next to me in the window seat, she keeps shifting uncomfortably, fidgeting with the pages of a paperback romance novel and sliding her pearl ring back and forth over the knuckles of her right ring finger. She gazes out the window at her reflection superimposed upon Magritte-like clouds, and I know she wonders whether she wants to unlock the memories of her childhood, to unleash a beast that has haunted her for half a century. She fears it may control her again, just when she was beginning to feel she controlled it. But another part of her wants to confront the past, to revisit the Motherland, hoping that going home will free her at last.

Each of us is all the places we have been, especially the place of our childhood. My mother says she is drawn back to her place.This journey was her idea. She insisted she needed to go, I supposed, to search for meaning in her aborted past. Or maybe just to see from where she came, to complete the circle, to round out her life. In her usual taciturn manner, she simply said, after fifty-two years: Its time.

I try to distract her by pointing out the windowpast her reflection, a self-portrait on glassto the occasional white clouds that dot the darkness beneath us. Even farther ahead is a spectacular light show featuring the dark colors of the rainbow, violet, magenta, grays, and blues. Here, where time and space are distorted, turned inside out, Im already in a land as foreign as Oz. Like Dorothy, I hope to learn here who I always have been.