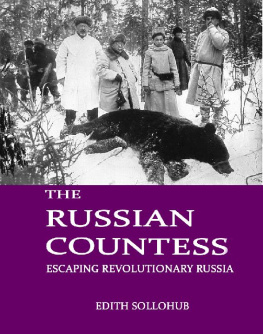

THE RUSSIAN COUNTESS

Escaping Revolutionary Russia

Edith Sollohub

Impress Books Ltd

2009

First Published 2009

by Impress Books Ltd

Innovation Centre, Rennes Drive, University of Exeter Campus,

Exeter EX4 4RN

Edith Sollohub 2009, 2010

Typeset by Swales and Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher

Dedicated to the memory of Nicolas Sollohub, who admired, cherished and supported his mother in her lifetime, and who was determined to preserve her writings so that her story would be known.

CONTENTS

Dedication

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

Map

1 Father

2 Travels

3 Petersburg

4 Waldensee

5 Marriage

6 Louisino

7 Kamenka

8 Wartime

9 The Revolution Comes

10 Revolution

11 Separation

12 Alone in Petrograd

13 Goodbye to the Past

14 Imprisonment

15 Release

16 Leaving Moscow

17 Mogilev

18 The Military Train

19 Baranowiczi

20 Wolkowysk

21 Escape

22 Reunion

Postscript

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

My Russian mother-in-law, Countess Edith Sollohub, born Edith Natalie de Martens, was well known in pre-revolutionary St Petersburg for accompanying her husband Alexander on shooting trips and for being outstandingly accurate with her gun. She was also the daughter of a high-ranking Russian diplomat, and was the mother of three young sons who would have been destined in due course to join the social and intellectual elite of imperial Russia. The Revolution of 1917 put an end to all that. By December 1918 her husband was dead, her children separated from her by the closing of the frontiers, and her own life in danger. These memoirs are her account of how she faced these disastrous events. They reveal how the courage and determination she had shown in earlier times now helped her to endure hunger, imprisonment, and loneliness. Her reunion with her sons in 1921 made the months of danger and deprivation finally worthwhile.

By the time I knew her, Countess Edith Sollohub was an old lady, fluent in four or five languages, glad to have helped her sons survive and become established in Western Europe. Her youngest son, a grown man in his 50s but still little Nic to her, was a teacher of modern languages in England, making use of the skills she had passed on to him. While struggling to cook and keep house for him, she liked to tell stories about her escape from Russia, and I had the privilege of hearing some of these in her own voice, with its distinctive accent and intonation. (One could still hear traces of the Scottish governess.) I learned that, quite soon after she reached the safety of France in the 1920s, she taught herself to type and began to record the story of her escape. She took a job as a typist in order to support herself and her sons in a one-room apartment in Paris. Only later, when her sons had grown up, did she have time to write the anecdotes about her childhood, her marriage and above all the influence of her father.

The memoirs were written entirely in English which even more than French became her preferred method of communication. No translation has been required. Such editing as was necessary lay in the chronological ordering of the typescripts and manuscripts that she had accumulated over the years. Most of the material was typed, with many deletions, overtyping and handwritten corrections. Her sons were able to use their knowledge of her handwriting to decipher any handwritten pages. On the advice of friends, and to avoid repetition, some childhood reminiscences have been omitted, and some shooting stories have been streamlined. But from the time of the outbreak of the Revolution onwards, the narrative is given in its entirety.

It was always her hope that her memoirs would find their way into print. When she died in 1965 she left the manuscripts to her youngest son. He, in turn, died in 1990 and as his widow I have been proud to prepare these memoirs for publication.

Valerie Sollohub,

widow of Count Nicolas Sollohub,

June 2009

Note

In order to preserve the authenticity of the authors own voice, transliterations from the Russian have been given mostly in the form she used, even if not necessarily conforming to a standard system. Baltic place-names have been left in the German forms which were current in Ediths own circles (e.g. Dorpat for Tartu, Reval for Tallinn). Polish place-names in the text were subject to spelling irregularities, which have now been re-shaped into some sort of consistency. Finally, where the names of certain key figures in the escape story had been replaced by initials in the original manuscript (because those people were still alive at the time of writing and should not have been identified), it has not been possible to discover or reinstate those names.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work of editing this book has been made easier by the help of many good friends and family members in England, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. In particular I wish to thank Ediths cousin in Basel, Johanna Mller-Vonder Mhll, who has been constant in her support over the years and who provided a number of family photographs. Thanks also to Angela Pullen for typing the first draft, working tirelessly to decipher Ediths original manuscript, to historian friends Mark Stephenson and Peter Gwyn for their encouragement, and to Catherine Hobey and Elizabeth Gordon for help with editing. Finally I am indebted to the younger, computer-literate generation my daughters Maria, Alexandra, Katherine and Natalia Sollohub for essential help in preparing the final typescript and placing it with the publisher.

PREFACE

I was born in Pavlovsk, near St Petersburg, on August 3rd, 1886. Both my parents were Russian though of Baltic origin, and were Lutheran Protestants which meant that they did not belong to the established state-church. My father was Professor of International Law at the University of St Petersburg, at the Lyceum and the Law School, as well as being a member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His name, Friedrich von Martens (or Frdric de Martens in French), had to be russianised and changed to Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens when he was acting for the Ministry. His work at the Ministry and the frequent special diplomatic missions abroad as well as a wide circle of friends brought us children in contact with international life from our earliest days. Foreigners were not strangers for us and we were taught to understand their points of view and to respect the habits and customs of various nations. Our first dancing lessons, when we were small girls of five or six, were with children from various embassies, and the daily papers lying on Fathers desk were newspapers not only in Russian but also in French, English, German, Dutch and Italian.

My brother Nicholas was six years older than I, and we had two younger sisters, Catherine and Mary. Our first languages were Russian, which we spoke in the nursery with our nurse, and French which was spoken at table with our parents. In winter, when we were at home in Petersburg, at Panteleimonskaya 12, on the corner of Mokhavaya Street, the Ptichia Komnata (Birds Room) was our realm. This was a large playroom in which there were two big cages full of canaries. Old Niania, who had started as my brothers nurse and who remained in our household for thirty-six years (until she died in the spring of 1918), looked after the canaries as well as the children, for she was extremely fond of all animals and birds. The Ptichia Komnata was a kingdom of its own where, under Nianias benevolent eye, we were free to do all we wanted, and we fully enjoyed our rights and privileges.

Next page