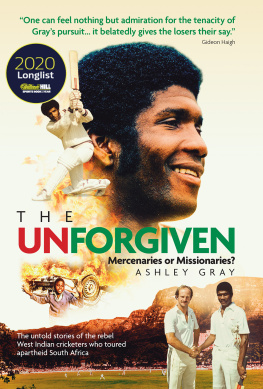

Ashley Gray - The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?

Here you can read online Ashley Gray - The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Pitch Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?

- Author:

- Publisher:Pitch Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published by Pitch Publishing, 2020

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Ashley Gray, 2020

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 9781785315329

eBook ISBN 9781785316968

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

For Archie, Harriet and Simone

About the Author

Ashley Gray grew up fending off bouncers and sledges in Newcastle, New South Wales, before moving to Sydney where he works as a sports writer and subeditor. His stories have appeared in Wisden Quarterly, Fox Sports, The Sydney Morning Herald, Daily Telegraph, The Guardian and All Out Cricket. He plays hard-fought backyard cricket with his young son and daughter, who are already showing a rare talent for destroying laundry windows.

Introduction

IT WAS October 1982. Prisoner 220/82, Nelson Mandela, was settling into his new home a cell in Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison. He had just endured 18 years imprisonment in the notorious Robben Island jail. Meanwhile, Hollywood superstar Liza Minelli was flying into Johannesburg for an 11-show engagement in Sun City.

On arrival at Jan Smuts Airport, she was mobbed by fans and journalists alike. The local newspaper couldnt contain its glee. Eat your heart out New York, it bragged, as Minelli swept into her hotel like a typhoon. Unsurprisingly, the same reporter made no comparison between the room Ms Minelli occupied and the one Mandela was forced to endure, 870 miles away on the outskirts of Cape Town.

Minelli wasnt the first celebrity to find the lure of the krugerrand stronger than any ethical concerns about visiting the apartheid stronghold. British singers Shirley Bassey, Elton John and Rod Stewart were hot on her stiletto heels, while tennis champion Billie Jean King declared ahead of an international tournament in the Transvaal capital, Ive been very keen to come to South Africa for a long time.

For those big names, and the local white audiences who craved their visits, that spring must have seemed reassuringly normal provided they turned a blind eye to the ugly reality within.

Furious white ratepayers in Durban, railing against black citizens having access to public toilets, alleging they would spread venereal disease. A gang of baton-wielding whites in Ermelo, attacking black guests at a Holiday Inn dinner-dance after learning of an interracial tryst. Frantic parliamentary debates over new influx controls, known as the Orderly Movement and Settlement of Black Persons Bill, which aimed to deny Africans the right to live in cities.

Racial discrimination buttressed by apartheid the enforced separation of minority groups was a feature of everyday life. It ensured the minority white population controlled the economic and social levers of the country.

But in a post-colonial world, South Africas version of normal was becoming increasingly repugnant to the global community. Fierce condemnation gathered pace. Suspension from the United Nations (UN) and Olympic Games, sporting boycotts and trade and cultural sanctions isolated the republic, gnawing at the fragile self-esteem of its white citizens. By hosting a steady stream of international pop stars, entertainers and sportspeople at its gold-funded stages and fields, a people under siege could present a business-as-usual facade to the outside world.

But playing sport in the pariah republic was now a tug-of-war between money and conscience that fewer were willing to tolerate. In 1977, Commonwealth heads of government drafted the Gleneagles Agreement, which discouraged all sporting links with South Africa. Three years later, the UN drew up an ongoing blacklist of those who had played there.

The Springboks had been locked out of world competition since 1970 as crickets controlling body, the International Cricket Council (ICC), demanded an end to segregated teams and integration on the pitch.

The likes of master batsman Graeme Pollock, dashing opener Barry Richards, and seasoned Test all-rounders Mike Procter and Eddie Barlow were confined to domestic or county competition in England.

The captain of that roll-call of Springboks legends was Ali Bacher. A doctor by profession, he became a successful administrator of Transvaal, transforming it into the feared mean machine that dominated South African provincial cricket in the 1980s. In 1982, he sat on the board of the South African Cricket Union (SACU). The previous year hed pulled off a major coup, luring West Indian left-hander Alvin Kallicharran a man whose brown skin deemed him a second-class citizen in South Africas racial hierarchy as their overseas professional. For his enterprise, the 66-Test veteran earned a Test ban from the West Indies Cricket Board of Control (WICBC).

Throughout the 1970s, South African cricket had attempted to reinvent itself by embracing non-racial selection policies. However, most black, coloured and Indian players were aligned to the rival South African Cricket Board (SACB), which refused to cooperate with the dominant SACU while apartheid was still in place. Its leader Hassan Howa rightly pegged integration as a form of window dressing designed solely to appease white liberals and convince the ICC that the Springboks were worthy of readmittance to the Test arena. The ICC wasnt convinced either. Pressure from anti-apartheid campaigners was now so intense that resuming Test contact with South Africa would have brought world cricket to its knees and created a racial schism between white and non-white playing nations.

With the door shut firmly on a return and fears the game would wither without further international stimulus, the chequebook became the SACUs sole tool of survival. Bolstered by a generous tax break that allowed sponsors to claim back almost 90 per cent of their outlay for international events, it was near enough to a government-sanctioned blank cheque.

Early in 1982, a bunch of over-the-hill and fringe English Test players were paid close to 40,000 each to participate in an eight-match tour of the outlier republic. Despite a three-year Test ban and howls of protest from black-consciousness groups in South Africa and the left side of British politics Shadow Environment Secretary Gerald Kaufman said the players were selling themselves for blood-covered krugerrands the tour was a minor success. It set the template for a further half-dozen.

Ali Bacher had little to do with that spectacle. He had his eyes trained on a bigger prize: the all-conquering West Indies side. But Caribbean involvement convincing black men to play in a country that systematically discriminated against people of their own colour was no certainty, and fearing another summer without international competition, a Sri Lankan rebel side was quickly cobbled together for the pleasure of Pollock, Richards and Procter. That they were substandard surprised nobody; what was more significant was the warm reception they received. To interested watchers, it showed that non-white sportsmen could tour the republic without incident.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?»

Look at similar books to The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Unforgiven: Missionaries or Mercenaries? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.