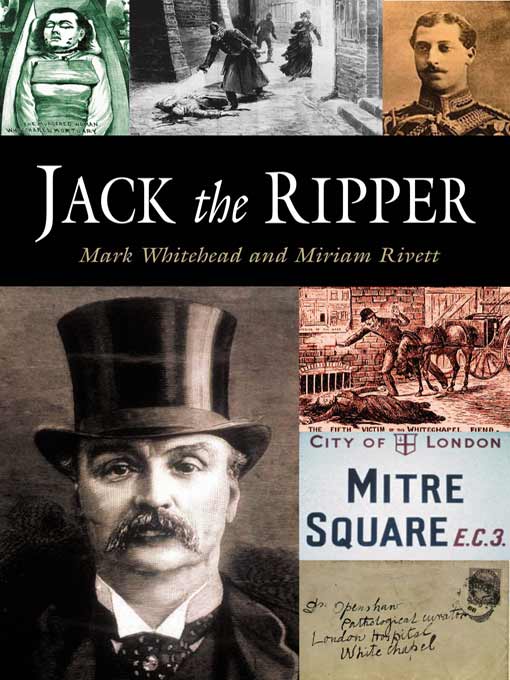

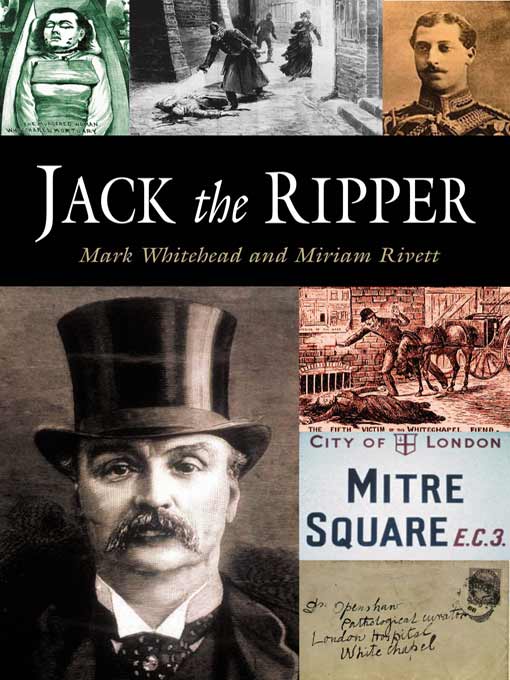

Jack the Ripper

MIRIAM RIVETT & MARK WHITEHEAD

POCKET ESSENTIALS

This edition published in 2006 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ www.pocketessentials.com

Mark Whitehead & Miriam Rivett, 2001, 2006

The right of Mark Whitehead & Miriam Rivett to be identi fi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publishers.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 10: 1 904048 69 2

ISBN 13: 978 1 904048 69 5

24681097531

Typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound in Spain

Other books in this series by Mark Whitehead:

Slasher Movies

Roger Corman

Animation

For Ian and Joel, who put up with endless

Ripper discussions,

and for Meryl, who knew it all already.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Paul, Ion and David, for patience, encouragement and books (you all know which).We would also like to extend our thanks to Philip Sugden, Paul Begg, Martin Fido, Keith Skinner, Stewart P Evans, Donald Rumbelow and Ross Strachan, whose research and diligence aided our own work invaluably.

Introduction

The Trouble with Jack

I was killing when killing wasnt cool Al Columbia

In this business no one knows anything William Goldman

You might not have heard of Amelia Dyer. In the late 1880s this ex-Salvation Army soldier fostered orphaned infants. While she collected their boarding fees, she swiftly disposed of her charges by strangling and dumping them in the Thames. She was known as The Reading Baby Farmer.

Nor may you have heard of Herman Webster Mudgett (aka HH Holmes). Mudgett ran a hotel in Chicago which bene fi ted in more ways than one from the 1893 Worlds Fair. A gothic eyesore, the place was a massive killing jar, full of secret entrances, trapdoors and hidden rooms. By the time the police twigged, Holmes had fl ed. Estimates of the dead found range from twenty-seven to over two hundred.

Or Rhynwick Williams. In 1790, he was arrested and tried as the London Monster.With over fi fty victims to his name, the Monster had been the terror of London women from 1788. He approached them with lascivious talk then slashed their buttocks with a knife.

Other names do stick in the mind. Brady and Hindley, Peter Sutcliffe, Fred and Rose West.They remain in our collective consciousness, their memory sustained by tabloid hysteria and broadsheet ponti fi cating. Their victims lives have been chronicled exhaustively through oral tradition, the media and by noted authors. The murderers lives continue to be scrutinised, each new event a source of outrage and discussion. All of it feeds our curiosity about Those Who Did What We Would Never Do.When Fred West committed suicide, it was a cause for populist, pun- fi lled celebration (Happy Noose Year! The Sun , the day after West hanged himself in jail).

And thats the real reason that they remain ever present. Its not outrage or grieving over the victims that really shift units or fi ll column inches. No matter how liberal we try to be, one word remains (and its not monster). The word is: Why?

There is a desire to understand what motivates such crimes. There has to be a reason, there just has to be. The detective approaches the subject by deductive reasoning, by using the grey cells whodunnits tell us this is so.They must know the motive to know the killer. The killer gets an opportunity to tie up any loose ends before they are led away. The motives are always there in a nebulous form: power, sex, boredom, money.These are universal things that tie us to Them. But its never the Reason. Thats personal, the collision of countless moments in time, emotions, desires, beliefs and the inde fi nable. Something We could never understand.

And still we search.

Theres another name that might just ring a bell. He remains in our collective consciousness, subject to occa-sional tabloid outbursts. His victims lives have been chronicled exhaustively over the past hundred-odd years. The murderers many, many possible lives continue to be scrutinised. Each new discovery about him is greeted with heated discussion. All of it feeds our curiosity about The One That Never Got Caught. Jack the Ripper. It is the perfect name for a villain. It is probably too perfect. The letters that gave him his name are most likely hoaxes perpetrated by a journalist wanting to boost sales, but the name remains. We know the name before we ever know anything about the case. Its as if weve been born with that name in our heads, part of our common mythology. Its all part of the trouble with Jack.

Jack, familiar name for John, a name of fairy tales and legends Jack the Giant Killer, Jack and Jill, Jack-Be-Nimble... Jolly Jack Tar (well, the Ripper was often described as wearing a sailors hat). London, no stranger to crimes or legends, had already been visited by one malevolent Jack in the 1800s. Spring-Heeled Jack, a fi re-breathing, metal-taloned monster capable of prodigious leaps, who attacked bewildered London suburb dwellers. His reign of terror from 1838 to around 1904 saw him enshrined in nursery folklore as a bogeyman and as a popular fi gure for the penny dreadfuls. Curiously, just as the new Jack moved into London, the old one was spotted in Liverpool.

The Ripper? Well, he certainly ripped up his victims, and several suspects were claimed to have threatened to rip up people. Late 19th-century slang already used the word to mean both a fi rst-rate man and a person who behaves badly. So was the name meant as a clue? Or was it used because it sounded cool or frightening? Thats the trouble with Jack. Everything has been analysed to the nth degree, everyone knows too much and yet no one knows anything.

Each new theory pores over the same details, the same cold entrails, searching for meaning, for an identity to leap out. Princes are named, doctors, writers, sailors. A game of cherry stones would be an equally useful divining tool. The trouble with Jack is that we can only build up his appearance through other peoples perceptions and experiences. What he did to his victims and the mixed descriptions of the sightings of men with the victims are continually cited. Everything is coloured by press reports, the publics reactions, the polices inability to fi nd so much as a trace of him and the memoirs and theories that paint many different pictures. Even by Hollywood. A man of medium build with a curled-up moustache and a sailors hat. A top-hatted, caped toff with a little black bag sweeping through a pea-souper. The devil himself. Jack shifts and morphs in our imagination the more that we read. And thats without his supposed diary.

The lies that surround him are enough to send anyone mad: He removed Kellys foetus (she wasnt pregnant), he fed his victims poisoned grapes (greengrocer Matthew Packer, the only witness to this fact, changed his story every day), he left ritualistic patterns of the victims belongings near the corpses (nope), and so on and on. Stephen Knight quotes The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (an early 20th-century anti-Semitic hoax) as being Masonic oaths. Donald McCormick dramatises scenes, complete with Cockney sing-songs, but insists that the dialogue is authentic. Jonathan Goodman named Peter J Harpick as a suspect, complete with background and history in his book

Next page