Jonathan Swift - Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions

Here you can read online Jonathan Swift - Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

GULLIVERS TRAVELS

Frontispiece engraved for Volume I, Mottes edition, London, 1726

Jonathan Swift

With an Introduction

and Contemporary Criticism

Edited by DUTTON KEARNEY

Ignatius Critical Editions Editor

JOSEPH PEARCE

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

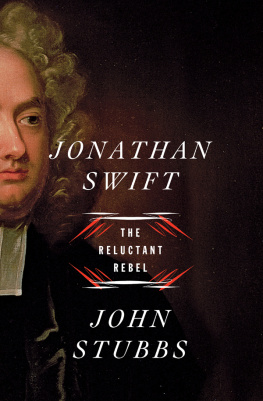

Cover art:

Illustration by A. E. Jackson for Gullivers Travels.

Chromolithograph, London & New York, 1911. Private Collection.

Photo Credit: Image Select / Art Resource, N.Y.

Cover design by John Herreid

2010 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-395-1

Library of Congress Control Number 2010923790

Printed in the United States of America

Tradition is the extension of Democracy through time; it is the proxy of the dead and the enfranchisement of the unborn.

Tradition may be defined as the extension of the franchise. Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our father. I, at any rate, cannot separate the two ideas of democracy and tradition.

G. K. Chesterton

Ignatius Critical EditionsTradition-Oriented Criticism for a new generation

Carol Abromaitis

Robert Scott Dupree

Mitchell Kalpakgian

Dutton Kearney

Douglas Lane Patey

Peter Stanlis

Portrait of Jonathan Swift, 1735

Dutton Kearney

Aquinas College

In the last chapter of Gullivers Travels, Jonathan Swifts narrator tells readers that his principal Design was to inform, and not to amuse thee (see p. 328). Swifts contemporaries would have immediately recognized an allusion to Horaces Ars poetica:

[O]mne tulit punctum, qui miscuit utile dulci

lectorem delctando pariterque monendo.

[The poet who pleases everyone (literally, the man who carries off every vote) is the one who blends the useful with the sweet, simultaneously amusing and informing the reader.]To eliminate amusement from literature is to act contrarily to the entire English literary tradition, which adopted Horaces counsel. From Geoffrey Chaucers description of The Canterbury Tales as tales of best sentence and most solas to Saint Thomas Mores frontispiece to his Utopia (A Truly Golden Handbook, No Less Beneficial than Entertaining), we repeatedly see this practice, which is arguably perfected in the playwright William Shakespeare, whose poetry is so delightful that readers and audiences are often unaware of the depths to which they have been instructed. These three examples of Chaucer, More, and Shakespeare have something in common beyond Horace: each of these artists has an implicit trust in his readers ability to comprehend a work of art.

Jonathan Swift, too, trusts in his readers capacity for reason, but Lemuel Gulliver, his narrator, does not. Although his readers have been following four major voyages full of miniature men, giants, ludicrous scientists, and talking horses, they are not to be amused, but to be informed. Gullivers outlook upon literature marks the end of one era and the beginning of another, the final end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the modern world, one that had been fully energized by its recent victory over the ancient world. In this new world, literature is a philosophical delivery system, a thinly disguised treatise whose teachings are to be extracted and put into practice and where delight is removed for the sake of utilitarianism. Literature is no longer a distinct mode of knowledge, an imaginative cosmos within which readers learn practical wisdom through characters choices and the consequences of those choices. If Swift (1667-1745) is the very last of the Renaissance humanists, then Gulliver is his successor, the first of the moderns.

Gullivers understanding of literature reveals his sympathies in the most important intellectual debate during Swifts lifetime, the Quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns (often referred to by its shortened French title, the Querelle). In the seventeenth century, claims were made that modern accomplishments in philosophy, science, art, and literature had eclipsed those of the ancient Greeks and Romansthe very models that had been imitated during the Renaissance. In the case of the sciencesand in particular, Isaac Newtons Principia of 1689these claims were true. However, in the case of liberal arts such as literature and philosophy, there were fiercely contested debates about Tassos or Miltons superiority over Homer, or whether Descartes had eclipsed Aristotle. From our contemporary perspective, such an argument may seem almost frivolous, but there was a remarkably robust debate at the time. At the heart of the debate was the moderns conviction that scientific progress necessarily corresponded to moral progress.

One of the participants in this controversy was Sir William Temple, for whom the young Jonathan Swift worked as a secretary. In his famous essay Upon the Ancient and Modern Learning, Temple attacked the members of the Royal Society, rejecting the doctrine of progress and supporting the virtuosity and excellence of ancient learning. Swift wrote some occasional and satiric defenses of Temples position, indicating his own sympathy for the ancients and his contempt for those, such as his own fictional creation, Gulliver, who supported the modern notion of progress. It is, therefore, crucial to a true understanding of Gullivers Travels to understand the critical distance between the author of the work and his fictional protagonist. Indeed, it would be more accurate to describe Gulliver as Swifts antagonist, or as his object of scorn and ridicule.

Unable to gain a preferment from King William III, Swift went to Ireland, where he was ordained in the established (Anglican) church. He traveled regularly between Ireland and England, eventually working as an editor of the Examiner, a pro-Tory (Royalist) newspaper that supported Queen Anne. Swift had hoped that his support would lead to an appointment as dean of Saint Pauls Cathedral, the most important church in England. The queen refused, and he became dean of Saint Patricks Cathedral, the most important church in Ireland. At her death in 1714, Swifts political ambitions effectively came to an end. During this time, he arranged for Esther Johnson and her elderly companion Mrs. Dingley to take up residence in Dublin. He had met Esther Johnson at Sir William Temples when she was eight. Johnson is better known as Stella, to whom Swift wrote many letters, published posthumously as his Journal to Stella. While traveling to London and writing letters to Stella, Swift appears to have caught the infatuation of Esther Vanhomrigh (whom Swift nicknamed Vanessa), who followed him back to Dublin in 1714. Vanessa died in 1723, and Stella died in 1728. Swifts relationship with these two women has been the object of much speculation in scholarly biographies.

Swifts constitution did not allow him to write lengthy discourses, so he turned to satire, the literature of disappointment. Almost all of the literature of Great Britain at this time had an air of disappointment about it, a disappointment that was connected to Charles IIs failure to live up to expectations following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Having endured a civil war and the increasingly unpopular commonwealth that followed in its wake, England was ready for peace again. Recalling the emperor Augustus, who locked the Janus Gates for the first time in the history of Romethe gates were to be kept open when Rome was at warcontemporary writers labeled this time as an Augustan Age. Unfortunately, as soon as it became clear that Charles II was more interested in being entertained than in picking up Octavians mantle, hope was exchanged for cynicism and satire. It is telling that Alexander Popes greatest work, The Dunciad (1743), ends on a note of pessimism, as universal darkness buries all (4.656). Two years after the publication of Popes magnum opus, Jonathan Swift, the last of the Renaissance humanists, died.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions»

Look at similar books to Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Gulliver’s Travels: Ignatius Critical Editions and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.