DRACULA

BRAM STOKER

DRACULA

With an Introduction

and Contemporary Criticism

Edited by ELEANOR BOURG NICHOLSON

Ignatius Critical Editions Editor

JOSEPH PEARCE

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover art:

Young Woman on Her Deathbed

Gabriel Cornelius von Max, 1876

Neue Galerie, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Kassel, Germany

Photo Credit: bpk, Berlin / Art Resource, N.Y.

Cover design by John Herreid

2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-494-1

Library of Congress Control Number 2011941428

Printed in India

Tradition is the extension of Democracy through time; it is the proxy of the dead and the enfranchisement of the unborn.

Tradition may be defined as the extension of the franchise. Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good mans opinion, even if he is our father. I, at any rate, cannot separate the two ideas of democracy and tradition .

G.K. Chesterton

Ignatius Critical EditionsTradition-Oriented Criticism for a new generation

CONTENTS

Introduction

Eleanor Bourg Nicholson

Draculas Guest

Bram Stoker

Religion and Superstition in Bram Stokers Dracula

Amanda Guilinger

The Cinematic Dracula: From Nosferatu to Bram Stokers Dracula

Jack Trotter

Professor, Psychical Research Agent, Detective: Van Helsings Role in Dracula

J.K. Van Dover

INTRODUCTION

Eleanor Bourg Nicholson

[T]o fail here, is not mere life or death. It is that we become as him.... To us for ever are the gates of heaven shut; for who shall open them to us again? We go on for all time abhorred by all;... an arrow in the side of Him who died for man.Rubbish, Watson, rubbish! What have we to do with walking corpses who can only be held in their grave by stakes driven through their hearts? Its pure lunacy.

Bram Stokers Dracula , that very weirdest of weird tales, is a living conundrum.

From its inception, Dracula received mixed reviews. The Athenaeum denounced it as highly sensational, but... wanting in the constructive art as well as in the higher literary sense, the Spectator called it decidedly mawkish even as it praised the book as a clever but cadaverous romance, and the Detroit Free Press declared it almost inconceivable that Bram Stoker wrote it. What is this strange novel? How has it endured? To answer these intriguing questions and to prepare those innocent and unsuspecting readers who are venturing into its clutches for the first time, the man behind the novel must first be introduced.

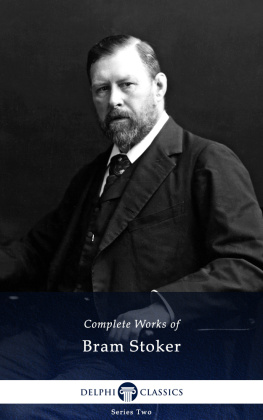

Abraham Bram Stoker, named after his father, was born at Clontarf, a seaside suburb near Dublin, Ireland, on November 8, 1847. He was the third of seven children of civil servant Abraham Stoker (1799-1876) and his young wife, Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley Stoker (1818-1901). Bram was sickly as a boy and was confined to his bed for a considerable amount of his childhood. His affectionate parents were attentive to their often lonely son; his mind and his imagination were richly nurtured through reading and daydreaming and, in a special way, through the dark and eerie Irish tales told him by his mothertales that established his lifelong fascination with fantasy and folklore.

The Stoker sons, owing to the ambitious determination of their mother, received university educations, establishing them as members of the Irish Protestant bourgeoisie. After attending the University of Dublin, Bram went on to read history, literature, mathematics, and physics at Trinity College. He was a successful student, graduating with honors. His early interests were not fully neglected: while at Trinity, he wrote a paper for the University Philosophical Society (for which he was elected president) entitled Sensationalism in Fiction and Society. Although he followed his fathers example in working as a civil servant, even going to the point of penning The Duties of Clerks later described as dry as dust by its authorhe still yearned for something beyond his chosen profession. In 1871 he began writing theater reviews for the Dublin Evening Mail . He even produced some fiction, including Under the Sunset (a collection of fairy tales for children, 1881), and The Primrose Path (1875), a short novel published in installments in an Irish weekly magazine.

In 1876 his life was completely changed through a meeting with the celebrated actor Henry Irving (1838-1905), who is often seen as a major inspiration for the character of Count Dracula. Two years after that momentous meeting, Stoker gave up the civil service, married the beautiful actress Miss Florence Balcombe (1858-1937)whose previous suitors included Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)and moved to London to serve as business manager of Irvings Lyceum Theatre in London. The following year, in 1879, Florence gave birth to a son: Irving Noel Stoker (1879-1961). Stokers relationship with the actor, which persisted and intensified until Irvings death in 1905, would prove one of the most defining of his life. As Sir Hall Caine remarked in Stokers obituary, I say without any hesitation that never have I seen, never do I expect to see, such absorption of one mans life in the life of another.

Indeed, for over two decades, Stokers life was entirely absorbed in that of Irving, with punctuating moments of individuality. In 1881 Stoker was awarded a medal for heroism after attempting to rescue a suicidal jumper who had leaped into the Thames River. He arranged European and North American tours for the Lyceum Theatre Company, and in 1883, during a tour in America, Stoker met both Walt Whitman (1819-1892) and Mark Twain (1835-1910). This expanded his familiarity with major writers of the day across the Atlantic; he already was personally acquainted with Oscar Wilde, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), and possibly Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873).

His writings at this time primarily concerned the Lyceum. His A Glimpse of America (1886) chronicled the companys touring experience, and a later collection of short stories was an obvious product of the same inspiration: Snowbound: The Record of a Theatrical Touring Party (1908). Stokers fiction attempts continued, though slowly. He published three novels in the early half of the 1890s: The Snakes Pass (1890), The Watters Mou&rsquo ; (1895), and The Shoulder of Shasta (1895). Meanwhile, he was in the midst of vast and disparate research projects for Dracula , which spanned from March 1890 (when his research commenced) until the novels publication in 1897. It was followed by Miss Betty (1898), The Mystery of the Sea (1902), The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), The Man (also known as The Gates of Life ; 1905), Lady Athlyne (1908), The Lady of the Shroud (1909), and The Lair of the White Worm (also known as The Garden of Evil ; 1911).

Soon after Irvings death in 1905, Stoker suffered a stroke. His career passed into a decline, with the exception of the publication of his Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (his greatest commercial success during his lifetime). Stoker died in 1912. Two years later, Florence Stoker published Draculas Guest, and Other Weird Stories (1914), a posthumous collection of her husbands previously unpublished stories, all of which continued in the horror and fantasy vein, though without even a fraction of the brilliance of his magnum opus. Dracula and its creator would remain largely ignored by critics until the publication of Phyllis A. Roths biographical work Bram Stoker (1982). The following year, Oxford University Press published an edition of Dracula in the Oxford Worlds Classics series. Ten years later Stokers biography appeared in Missing Persons , a special supplement to the Dictionary of National Biography .

Next page