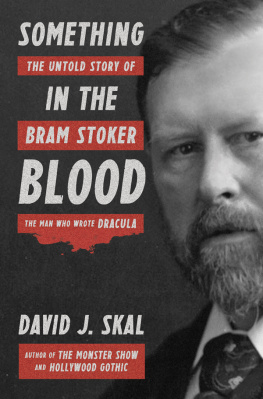

OTHER BOOKS BY DAVID J. SKAL

NONFICTION

Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen

The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror

Screams of Reason: Mad Science and Modern Culture

Dark Carnival: The Secret World of Tod Browning

(with Elias Savada)

V is For Vampire: The A to Z Guide to Everything Undead

Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween

Claude Rains: An Actors Voice

(with Jessica Rains)

Romancing the Vampire

FICTION

Scavengers

Antibodies

When We Were Good

EDITOR

Dracula: A Norton Critical Edition

(with Nina Auerbach)

Dracula: The Ultimate, Illustrated Edition of the World-Famous Vampire Play

Copyright 2016 by David J. Skal

All rights reserved

First Edition

A shorter version of chapter 1 originally appeared in Bram Stoker: Centenary Essays , published by Four Courts Press, Dublin. Copyright 2014 by David J. Skal. All rights reserved. A short section of chapter 4 first appeared in The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature , published by Swan River Press, Dublin (Autumn 2015). Copyright 2015 by David J. Skal. All rights reserved. Selected passages in chapter 6 expand on material first published in Screams of Reason: Mad Science and Modern Culture , published by W. W. Norton & Company, New York and London. Copyright 1997 by David J. Skal. All rights reserved. Brief sections of chapter 11 are excerpted from the authors essay Dracula: Seen and Unseen, originally published in Dracula in Visual Media , published by McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, and London. Copyright 2010 by David J. Skal. All rights reserved.

Drawing of Frank Langella as Dracula The Al Hirschfeld Foundation.

www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org. Al Hirschfeld is also represented by the Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd., New York.

A full search of copyright registration records has been conducted for all illustrations used in this book. Any omission of credit is inadvertent, and the author and publisher will make any necessary acknowledgment in future editions. Unless otherwise indicated, all images are from reproductions and originals in the collection of the author.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Faceout Studio

Production manager: Julia Druskin

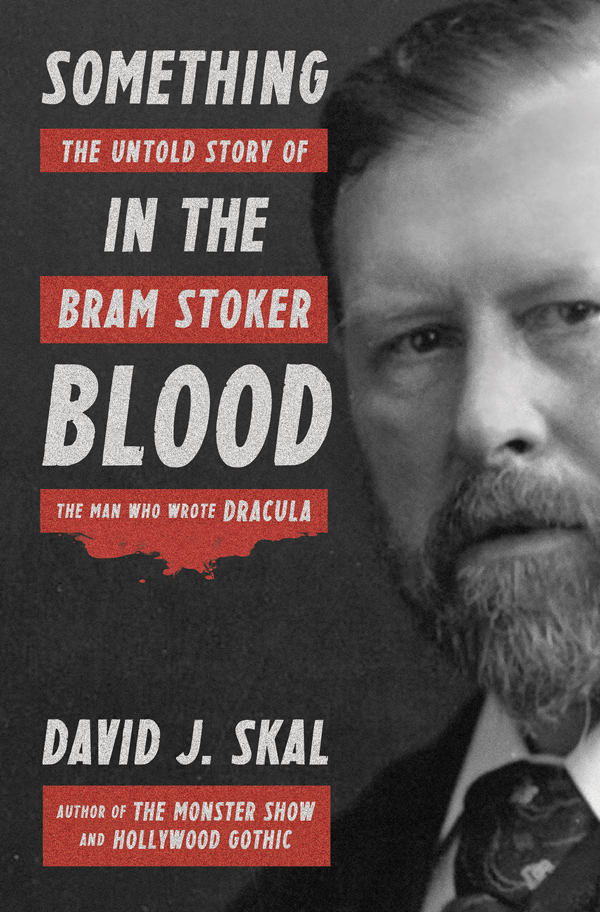

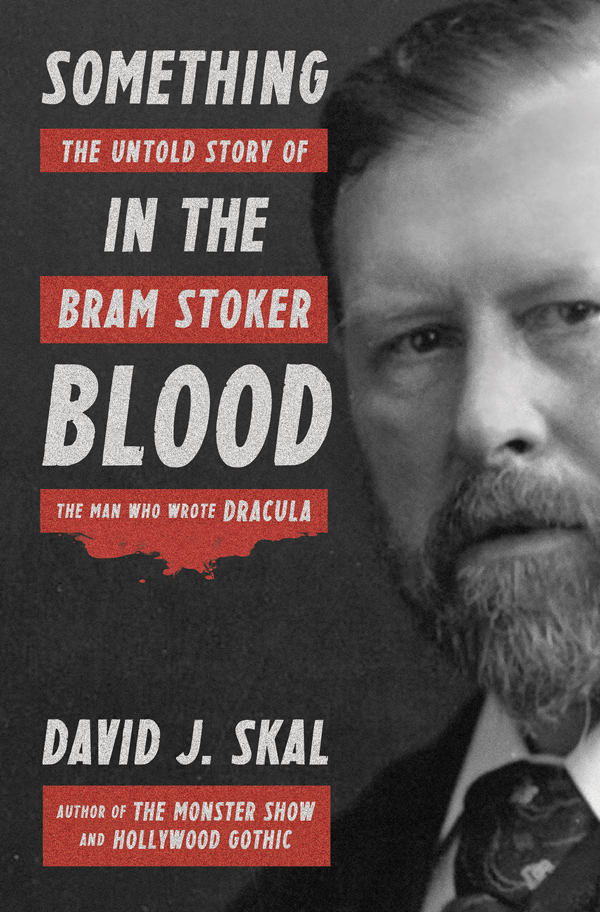

Jacket design by Rodrigo Corral

Jacket photograph by Kerrick James / Corbis

ISBN 978-1-63149-010-1

ISBN 978-1-63149-011-8 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

for

PETER GLZ

CONTENTS

Lets root out Brimstoker and give him the thrall of our lives.

JAMES JOYCE, Finnegans Wake

The only known photograph of Bram Stoker writing.

WHAT MANNER OF MAN IS THIS?

Bram Stoker, Dracula

There are no photographs of Bram Stoker smiling.

The real Bram Stokerat least the human being verifiably documented, dozens of times, by a succession of curious cameras over a period of six decades, from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentiethis serious, studious, at times stuffy, and very often startled-looking. He doesnt enjoy being scrutinized. The image is completely at odds with a lifetime of people describing a warm and genial man brimming with Irish good humor. In his working notes for Dracula , he imagines that his vampire king also has an image problem, namely that photography has the power to penetrate his flesh, starkly revealing his skeletal core. Painters cant see the skeleton, or capture Draculas likeness at all. The finished canvas always looks like someone else.

Stokers earliest photographic portrait, and the only one that survives his childhood, shows an uncomfortable-looking boy of eight in a suit of breeching clothes staring directly at the camera, as if wondering what is expected of him. It is a characteristically haunted expression, one that would be repeated many times in his life, whenever a camera closed in. Haunted is a particularly good word for a youngster whose memories prior to the age of eight revolved around disease and hovering death, and whose legacy would center on a fantastic revenant impervious to both.

A previous biographer complained that Stoker dispersed memories as selfishly as an old crone ladling soup. And its true. He left behind no real accounting of his life, almost no candid or personal writings. As a result, much of what has been written about Stoker has focused on the amply documented minutiae of his long employment as business manager for the great Victorian actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, which only deflects attention from the question that has always interested readers most: What, exactly, was going on inside the head of the man who wrote Dracula ?

Stokers prodigious capacity for work (for instance, writing as many as fifty letters a day for Irvings signature) and the extra reserves of energy that fueled the furious production of potboiler novels in his supposed spare time have mostly been treated with awestruck admiration. The modern concept of workaholism was unnamed and unacknowledged in Stokers time, but he was the very Victorian model of overcompensation and insecurity. The Protestant work ethic has always had a problematic dark side, and it was a realm Stoker inhabited with a frightening force.

Stoker chronicles have also suffered from a dismaying echo-chamber effect, as certain assumptions and factoids have been repeated so frequently they are accepted as gospel. For instance, to what degree did Stoker take inspiration from the legend of the Wallachian warlord Vlad the Impaler, aside from borrowing his historical sobriquet Dracula? The answer is really not mucheven if the idea has given birth to self-sustaining cottage industries of commentary, criticism, and filmmaking. And what about the widely accepted notion that Irving himself was the direct model for Dracula? Here, the truth is more nuanced. Certainly, Irvings celebrated impersonation of Mephistopheles in Faust bears a family resemblance to the master vampire, or at least to the sardonic, charming Draculas that evolved in the twentieth century, owing very little to Bram Stokers character. Dracula indeed has theatrical origins, but the Counts essential roots are better traced to the demon kings of the Christmas pantomimes that first ignited Stokers imagination as a boy. His rapturous and only recently rediscovered writings on these traditional theatrical wonder tales are revelations, and you can read them in this book for the first time since he put them to paper. Just as Dracula would become a frightening fairy tale for adults, Irvings Faust , with more than a little help from Stoker, found success as a kind of grown-up pantomime from hell.

Next page