Contents

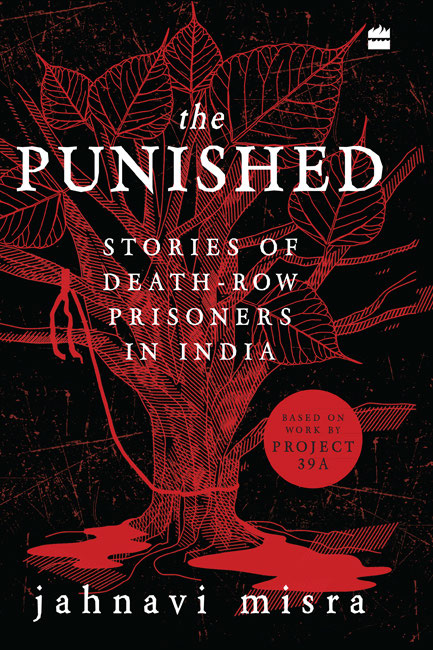

THE Death Penalty Researh Project at National Law University, Delhi interviewed nearly 400 prisoners sentenced to death and their families between 2013-16. Nothing could have prepared me for the experience of interviewing death-row prisoners and sitting in those dark, oppressive prisons across different parts of India. I realised that my decade-long legal education had not prepared me for the sheer force of the human experience that I was witnessing. No amount of intellectual sophistication could have equipped me to deal with the raw emotion of hundreds of prisoners constantly swinging between the hope for life and the fear of death. It is hard to explain those settings the sense of expectation, the stark hopelessness and the cruel reality of incessantly anticipating ones own death. The researcher is a curious being in the midst of all this. Giving effect to the permissions from higher ups, prisoners sentenced to death were told to talk to us by prison officials and didnt really have the choice to refuse. As researchers, we were strangers suddenly prying into the darkest aspects of their lives, asking them to immediately trust us with their innermost feelings of anger, frustration, shame, fear, hope and everything else in between. Against the ticking clock set by prison officials, we were invariably in a tearing hurry to open up their lives, making them relive some of their most traumatic episodes, only to suddenly disappear after having documented what we wanted.

Across different prisons, death-row prisoners almost always saw us as people who had come from Delhi with the power and the resources to alter their fates. The guilt of knowing their interest in talking to us and our inability to help even in the smallest measure was often overwhelming. In those moments of expectation, to repeatedly tell them that we could not offer any kind of legal assistance and to choose research ethics over addressing their suffering was a demanding moral burden. All that we had to offer in return was taking their stories and suffering to the outside world. We were repeatedly asked if our research would help them, only for us to convey our embarrassment and helplessness by saying that we couldnt be sure. In many ways they understood that their stories would speak to a future time, and that they themselves might be in no position to benefit from it.

Even in courtrooms, they are often defined by their crimes alone and very little else. Despite the law requiring that a much broader canvas about their lives be considered during sentencing, their stories barely ever enter the courtroom. Hamstrung by their poverty and inability to afford effective legal representation, their stories are neither presented nor demanded in any real sense. The silence about their lives is only louder in the public conversation on the death penalty. Given the crimes in question, the shrillness of public discourse reduces the death-row prisoner to one event in their lives. It is almost as though we are afraid to find out anything more making it a ritualistic necessity that we first dehumanise a person before executing them. These stories are an attempt to shatter that moral simplicity and comfort, and present death-row prisoners as individuals with complicated inner lives.

An equally important part of the project was to interview the families of death-row prisoners. In awarding and executing death sentences, the public imagination has very little space to consider the pain being inflicted on the family members of the prisoner. Given the tremendous public pressure in these cases, the families of death-row prisoners end up leading an immensely vulnerable and alienated life. Poverty, social boycott, ridicule and threats of violence are all tragic realities of their lives. They are people everyone forgets. I assume we tuck them away in some corner of our mind as the unfortunate but, perhaps, necessary cost for the retributive justice that we seek.

Our work after the Death Penalty India Report has involved providing pro bono representation to prisoners sentenced to death. As part of that representation, we carry out what are called mitigation investigations to reconstruct the lives of prisoners in order to present it in court as sentencing information for judges to consider. Compared to the limitations of the single-conversation format of the Death Penalty Research Project, mitigaton investigations have a much longer and deeper arc with many more conversations with the prisoner, their family members, friends, colleagues, partners and acquaintances. Building trust and confidence for people to talk about their lives without the fear of being judged or abandoned is a time consuming process. But at the end of that process, what often emerge are narratives of people whose lives go farther than single incidents in their lives.

While the Death Penalty India Report published in May 2016 was an academic endeavour based on these interviews, this collection of stories is an effort to bring the complex realities of their stories to a much larger audience. I have no illusions about these stories convincing people to oppose the death penalty. That is a longer and more arduous task. These stories are meant to put forward a human understanding of those we condemn to a life of misery, suffering and pain.

All of us at Project 39A and National Law University, Delhi cannot thank Jahnavi enough for transforming our research into the profoundly moving stories you will read in this book. It was inspiring to see the stories break out from the confines of academic writing. None of this research would have been possible without the massive contributions of the student researchers at National Law University, Delhi. Meeting prisoners and their families while listening to stories challenged and moved them profoundly and has deeply influenced their thinking about the role of law in our society.

Since we conducted these interviews, we have lost some of the prisoners to illnesses in prison, death by suicide and the ultimate aim of the death penalty death by hanging. Some of them have been acquitted and released and some had their death sentences commuted to life in prison, but many continue to live under the shadow of the death penalty. The stories in this volume are written with the hope to make readers understand the people we want to kill. It is as much about the lives of prisoners and their families as it is about holding a mirror to society. Ultimately, it is an appeal to the humanity in all of us to know a little more about the people whose lives we want to take.

Anup Surendranath

November, 2020

Delhi

WE all sat down on the floor of their hut. The mother wiped her tears and said that she could not bear to hear her husbands ramblings, and left on an errand. The father was free to say what he wanted. Tell us what happened that night, we asked.

The policemen barged into our home and said, Come with us right now! My elder son insisted that we did not know where Rajni was, but they shoved and kicked us till we got into the van. The nasha that was supposed to get me through the night left my body so quickly that it felt like the twenty rupees and two hours I had spent drinking that evening had only been a dream. When we got to the police station, we saw that my daughters husbands had been picked up from their homes too. I will not lie, seeing them there was a bit of a relief. But then the beatings started. Tell us where he is!, the policemen yelled as they lashed us with lathis. Even my wife received a couple of slaps. It is wrong to beat us like this. We have not done anything wrong, the stupid woman kept repeating.

Next page