The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright 1989 by Toby Byron/Multiprises

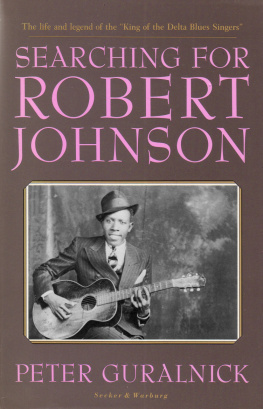

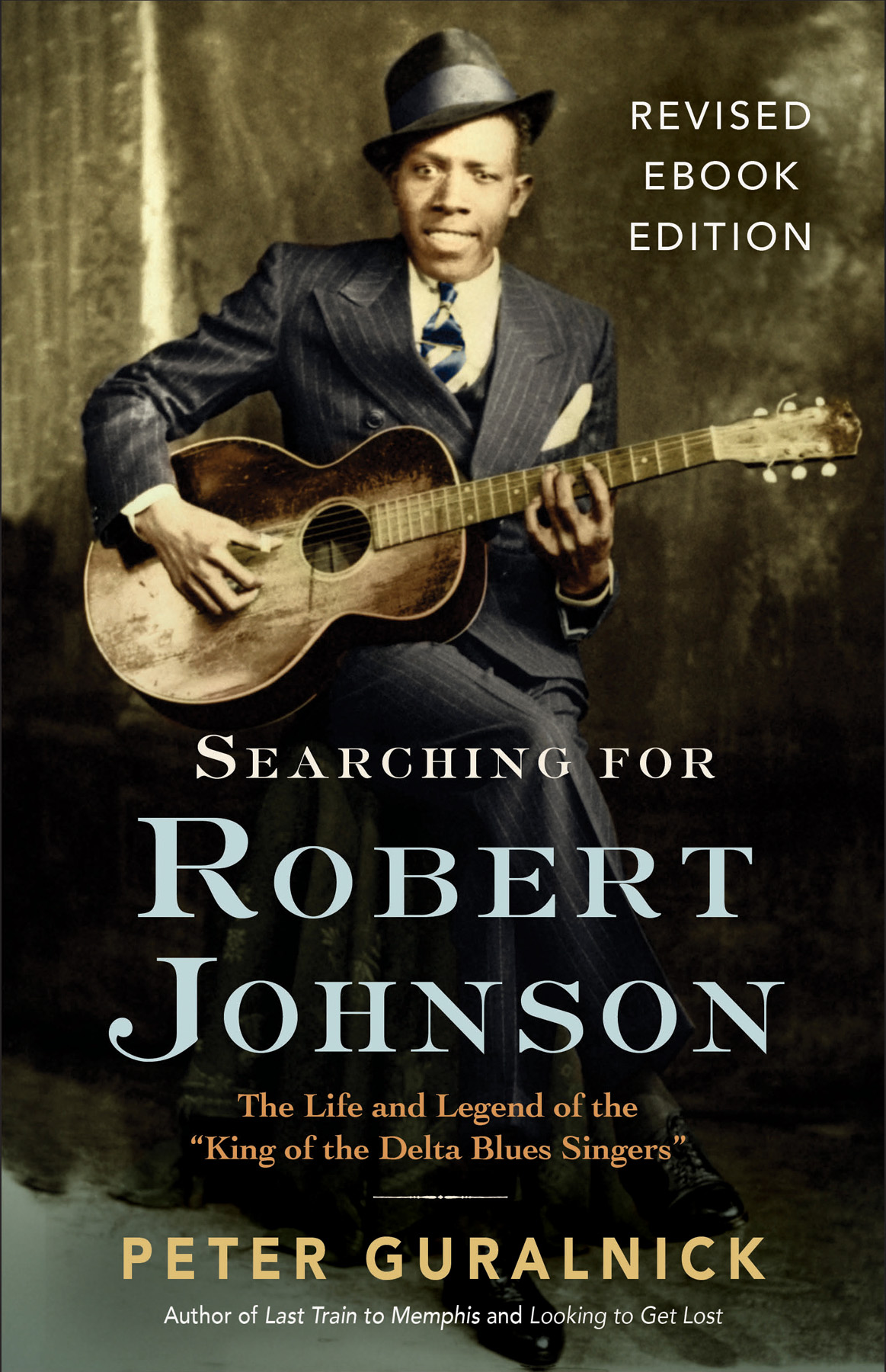

Text copyright 1982, 1989, 2020 by Peter Guralnick

Cover Design by Mario J. Pulice

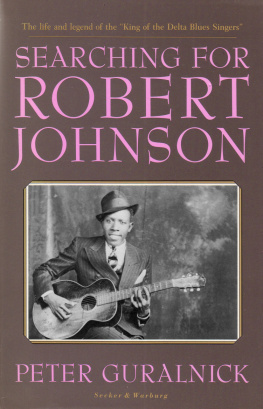

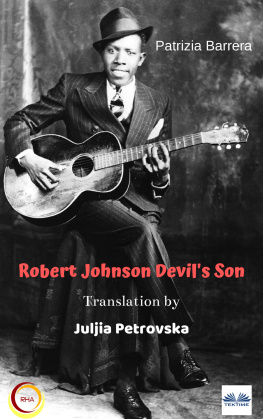

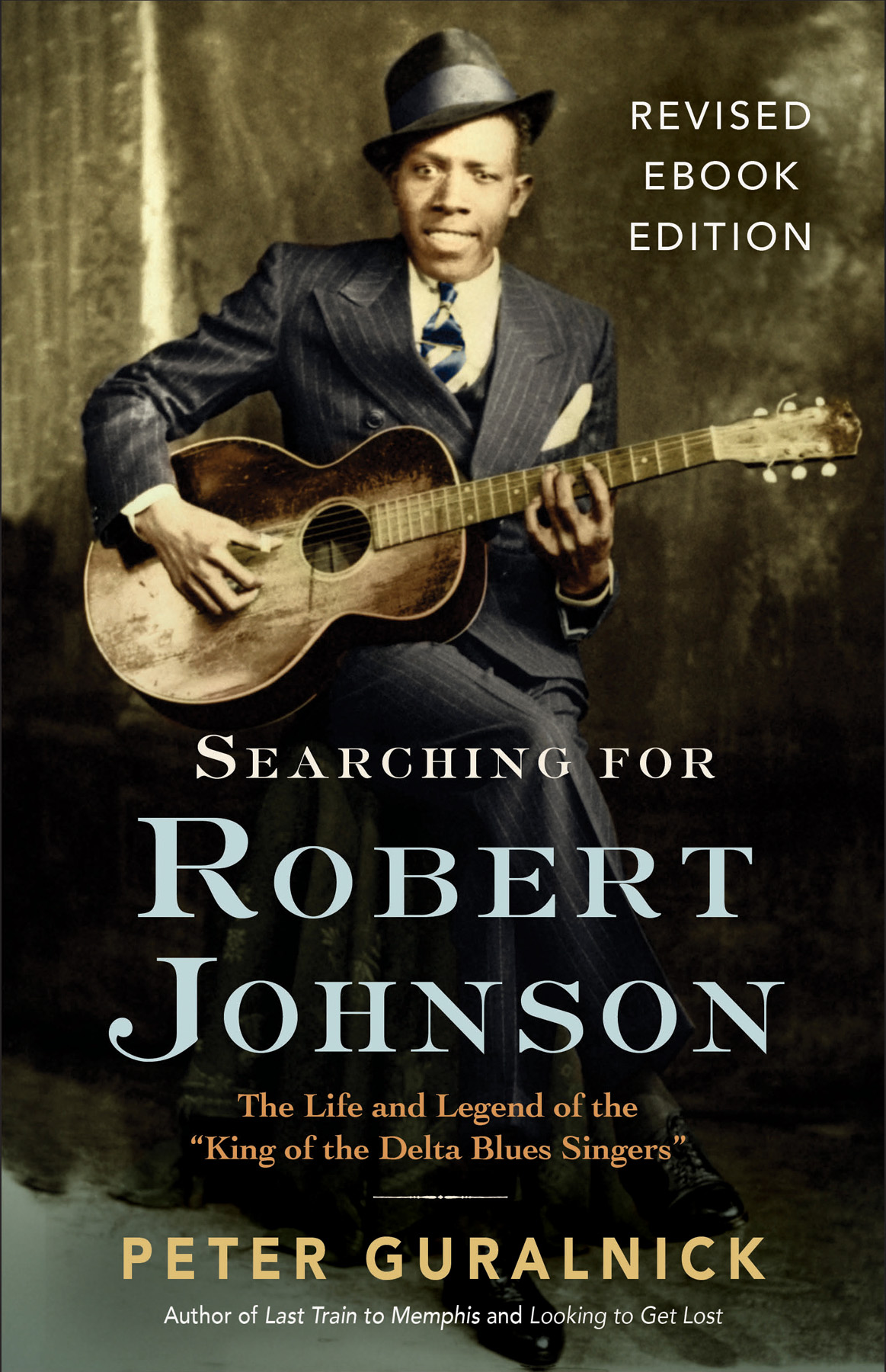

Cover and title page photograph: Robert Johnson, ca. 1936. Courtesy of Steve Lavere, 1989

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: August 2020

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The author and publisher wish to thank the Delta Haze Corporation for granting permission for the use of the photographs of Robert Johnson and his mother. The Robert Johnson song lyrics are reprinted by permission of King of Spades Music.

ISBN 978-0-316-30437-5

E3-20200828-JV-PC-REV

For Sam Charters, Mack McCormick, and Chris Strachwitz, who introduced me to the blues through their work and for my friend Bob Smith, who leapt at the invitation.

WHEN I WAS A FRESHMAN in college, in 196162, my most precious possessions were my blues records and a portable stereo phonograph which my mother had uncharacteristically purchased with green stamps. From time to time I read and reread Samuel Charters pioneering The Country Blues, published in 1959, for its poetic descriptions of a music that seemed as remote as Kurdistan and destined always to remain so. I had perhaps fifty albums of country bluesLightnin Hopkins, Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Furry Lewisit seemed as if there could scarcely be any more. Names that are as familiar as presidents today, touchstones for anyone familiar with the roots of contemporary music, were the exclusive province of collectors then. My friends and I studied the little that was available, attempted to piece together virtually indecipherable lyrics, pored over each precious photograph, constructed a world of experience and feeling from elliptical clues. Of all the figures who beckoned to us from a remote, mysterious, and foreign pastcertainly it was a past that was not our ownRobert Johnson stood out, tantalized, really, in a way that no other myth or archetype has ever done. Lightnin Hopkins, the first real blues singer I had ever seen live, was, in Charters words, the last of the great blues singers, but the ethos of Robert Johnson was nowhere near so prosaic. Almost nothing, Charters wrote in a chapter that consisted for the most part of song quotes, lyrical tormented quotes, is known about his life. He is only a name on a few recordings. The finest of Robert Johnsons blues have a brooding sense of torment and despair. His singing becomes so disturbed it is almost impossible to understand the words. The voice and the guitar rush in an incessant rhythm. As he sings he seems to cry out in a high falsetto voice.

What could be more appropriate to our sense of romantic mystery than an emotionally disturbed poet scarcely able to contain his brooding sense of torment and despair? Just as we imagined that Tommy McClennan was mad from the ferocity of his growl, that Blind Willie McTell was the unlikely reincarnation of a latter-day Flying Dutchman with his uncanny ability to turn up in the recording studio at least once in every decade, so Robert Johnson became the personification of the existential blues singer, unencumbered by corporeality or history, a fiercely incandescent spirit who had escaped the bonds of tradition by the sheer thrust of genius. Incredibly, all of this apostrophizing was based solely on Charters chapter and one recorded selection, Preachin Blues, on which Johnson sounded somewhat thin, constricted, and out of control.

That is why I remember so vividly walking into Sam Goodys on 49th Street in New York, riffling through the blues section with a practiced eye, and discovering to my utter amazement (for there had been no announcement that I knew about; there was no place where you could conceivably read about such things) not one but two altogether unanticipated treasures: Big Joe Williams Piney Woods Blues on the Delmar label, and Robert Johnson: King of the Delta Blues Singers. I held the records in literally trembling fingers, pored over the notes in the store, studied the romantic cover painting of an isolated, featureless Robert Johnson hunched over his guitar, paid the $2.89 or so that a record cost then, and took the subway back to Columbia without making any of my other intended stops. I probably listened to each record half a dozen times that day.

Sometimes I can evoke the breathless rush of feeling that I experienced the first time that I ever really heard Robert Johnsons music. Sometimes a note will suggest just a hint of the realms of emotion that opened up to me in that moment, the sense of utter wonder, the shattering revelation. I dont know if its possible to re-create this kind of feeling todaynot because music of similar excitement doesnt exist, but because the discovery can no longer take place in such a void. Or perhaps there is someone right now who will come to Robert Johnson, or a contemporary pop star, or a new voice in jazz, or some music as yet wild and unimagined, with the same sense of innocent expectation that caused my friends and me to hold our breath, all unknowing, when we first played Robert Johnsons songs on the record player. Let me just quote a passage from Rudi Blesh on which an older generation of blues enthusiastsMack McCormick, Paul Oliver, probably Sam Charterswas nurtured and which expresses, I think, that same sense of pure romantic surrender. It describes Johnsons masterful Hell Hound on My Trail in words that come close to mocking their meaning and yet evoke that same sense of awe I am trying to suggest.

The voice sings and thenon fateful descending notesechoes its own phrases or imitates the wind, mournfully and far away, in huh-uh-uh-ummm, subsiding like a moan on the same ominous, downward cadence. The high, sighing guitar notes vanish suddenly into silence as if swept away by cold autumn wind. Plangent, iron chords intermittently walk, like heavy footsteps, on the same descending minor series. The imagesthe wanderers voice and its echoes, the mocking wind running through the guitar strings, and the implacable, slow, pursuing footstepsare full of evil, surcharged with the terror of one alone among the moving, unseen shapes of the night. Wildly and terribly, the notes paint a dark wasteland, starless, ululant with bitter wind, swept by the chill rain. Over a hilltop trudges a lonely, ragged, bedeviled figure, bent to the wind, with his