whose ideas formed the foundation of this work.

Scholars love to praise the pure blues artists or the ones, like Robert Johnson, who died young and represent tragedy. It angers me how scholars associate the blues strictly with tragedy.

B. B. KING

Blues is not a dream. Blues is truth.

BROWNIE MCGHEE

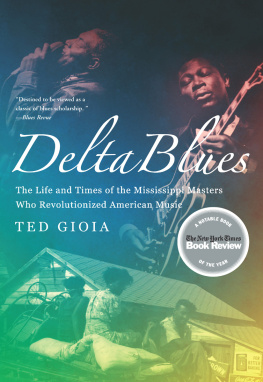

F OR ITS FIRST FIFTY YEARS, BLUES WAS PRIMARILY BLACK POPULAR music. Like rappers or country-and-western stars, the top blues singers were assumed to come from poor backgrounds and to understand the problems and aspirations of folks on the street or out in the country, but they were also expected to be professional entertainers with nice cars and fancy clothes, admired as symbols of success.

In the 1960s, a world of white and international listeners discovered blues, and for roughly the last forty years, the style has primarily been played for a white cult audience. This audience has generally considered blues singers to be purveyors of a wild, soulful folk art, the antithesis of glitzy pop entertainment. Even at the pinnacle of commercial success, an artist like B. B. King is considered by the mass media to be a roots musician, described in very different terms from either a Duke Ellington or a Van Morrison. It is common to hail blues artists not for their technical skill or broad musical knowledge, but rather for their authenticity. By this standard an unknown genius discovered in a Louisiana or Mississippi prison is by definition a deeper and more real bluesman than a million-selling star in a silk suit and a Cadillac.

Such standards framed my own introduction to blues, and though I now consider them pure romanticism, an outsiders perception that has virtually no bearing on the realities of the music, my tastes remain largely unchanged. I am not a mainstream pop fan. If a record sounds like hundreds of other records, that diminishes my appreciation of it. I want to hear unique, personal work, and my interest is even greater if that work provides a window into a world or culture that is unfamiliar to me. That is part of what attracted me to blues, and I continue to share much of the aesthetic that drives other contemporary blues fans. We love the music as a heartfelt, handmade alternative to the plastic products of the pop scene, and when we listen to older records it is as natural for us to prefer Charley Patton or Robert Johnson to the more popular urban blues singers of their day as to prefer Lester Young to Guy Lombardo, Tom Waits to Billy Joel, or Cesaria Evora to Christina Aguilera.

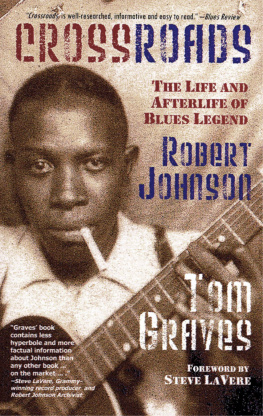

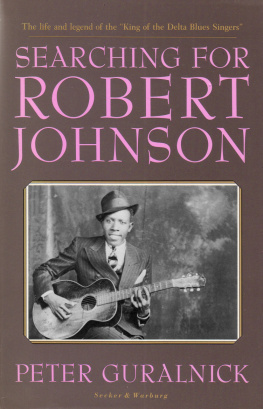

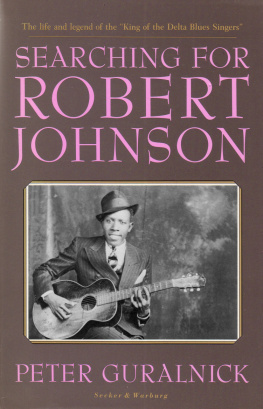

Because of this, writers like myself have tended to shy away from the fact that blues was once popular music. Its evolution as a style, and the career paths of most of its significant artists, were driven not by elite, cult tastes, but by the trends of mainstream black record buyers. Hard as it is for modern blues fans to accept, the artists we most admire often shared the mass tastes we despise, and dreamed not of enduring artistic reputations but of contemporary pop stardom. Nothing we know about Robert Johnson suggests that he aspired to be a Mozart or Keats, a tortured genius dying young but leaving a timeless legacy. Everything suggests that he hoped to make it on the commercial blues scene, to be the next Leroy Carr, Kokomo Arnold, or Big Bill Broonzy. Indeed, while white fans often imagine that if he had survived into the electric era he would have been tearing off screaming Delta slide licks la Elmore James, his black musical companions are more inclined to suggest that he would have been as slick and expert as T-Bone Walker, complete with a horn section and a zoot suit.

Instead, he died virtually unknown in a rural backwater, without making any appreciable dent on the blues world of his day. It was only after blues had largely disappeared from the black charts and had been revived as a nostalgic adjunct to the white folk and rock scenes that he became famed as the most influential and important bluesman of all time. On purely artistic grounds, his posthumous acclaim may be deserved. The early Mississippi mastersCharley Patton, Son House, Skip James, and a handful of othersare among the greatest musicians this country has produced, and Johnsons work can be seen as summing up their tradition. Still, that does not give his fans the right to rewrite history, and the historical evidence is clear: As far as the evolution of black music goes, Robert Johnson was an extremely minor figure, and very little that happened in the decades following his death would have been affected if he had never played a note.

So why do I still take Johnson as my central figure for a book on blues history? There are two reasons:

The first is that he is the only prewar blues artist whose records are still widely owned and heard today, and therefore he is the natural starting point for modern listeners who want to delve more deeply. Because he recorded so little, most blues fans own his complete works, so I can assume that readers will have the basic source material available. His unusually broad grasp of the popular styles of his day makes these recordings a particularly good door into the larger musical world around him, and the fact that he arrived relatively late on the scene means that most of his roots and influences are accessible to us.

The second is that the odd evolution of blues and its audience is perfectly exemplified by the paradox of Johnsons reputation: that his music excited so little interest among the black blues fans of his time, and yet is now widely hailed as the greatest and most important blues ever recorded. Since all blues history was written retrospectively, this paradox has rarely been stressed. Therefore it is difficult for modern readers to understand quite how differently the music was seen in the days when it was a mainstream black pop style rather than magnificent folk art.

Due to a combination of taste and accident, Robert Johnson has served from the beginning as a unique bridge between two very different worlds. For his original fans, he was a bridge out of the Delta, a young local player who had managed to assimilate all the latest styles from the radio and the jukeboxes, and to perform them as well as the big stars in St. Louis and Chicago. For the small group of urban white blues fans that eventually grew into a huge audience that remains largely urban and white, he was a bridge in the other direction, taking us from our world into the deep blues of the older Delta players. In both cases, Johnson has served as a screen on which each group of fans projected its own dream movie of the blues life. For his peers in Mississippi, he was a hip, smart adventurer who had traveled to northern cities and lived high, wide and free. For a modern audience of college students, rock musicians, and historians, he has been the dark king of a strange and haunting world, lost in the Mississippi mists and harried by demonsa legend more earthy, violent, and passionate than anything in our daily lives. Amidst all the mythologizing, it is not easy to stand back and treat Johnson as a normal human being, a talented artist who came along at a particular period in American music, and to try to understand his world and his contribution rather than getting lost in the clouds of romanticism.

I STARTED PLAYING BLUES GUITAR in my early teens, and I had been working the folk circuit for a dozen years before I first went to Mississippi. That was in 1991, and strangely enough I was there to play at the dedication of Robert Johnsons grave marker. Washtub Robbie Phillips, my regular bass player, had been invited by the organizer of the ceremony and had just won a thousand dollars on the lottery, providing us with gas money. I had a car, and our friend Kenny Holladay, a slide guitarist based in New Orleans, agreed to meet us in Clarksdale. We understood that there would be some real Mississippi bluesmen performing at the ceremony, but that maybe we would be allowed to play a tune. As things turned out, none of the other musicians showed up, so we were the band.