The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Betrayal is the only truth that sticks.

The squealer must die.

November 12, 1941

The sun rose at 6:39 a.m. that morning over a sea the color of dishwater. The first light of a cold fall day shone on the Coney Island pier, stilted above a scouring shore break. It shone on the rickety wood latticework upholding the Cyclone roller coaster and on the round immensity of the Wonder Wheel with its crisscrossed spokes. Seagulls barked. A few fishermen casting for bluefish may have left a trail of footprints on the beach, but Coney Island was otherwise a ghost-town version of its summer self. A stiffening onshore wind kicked up whitecaps and whistled among shuttered penny arcades and souvenir shops. In mid-November, gaiety was on off-season hiatus.

Two full years had passed since the Nazis blitzed Poland. Afterward the poet W. H. Auden sat in a Fifty-second Street dive bar, in Manhattan, and wrote these lines:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth

Anger and fear were in full supply in the fall of 1941. America was not yet mobilized for war, but the nation braced for the inevitable. Banner newspaper headlines reported torpedoed British destroyers sinking into the cold North Atlantic and Wehrmacht tanks rolling to the outskirts of Moscow. President Franklin Roosevelt had initiated the first peacetime draft in order to begin military training. The preparation for war reached even here, on this bleak barrier beach where New York City faced the Atlantic Ocean.

At 7:15 a.m. William Nicholson, chief clerk of the Coney Island draft board, entered his office in room 123 of the Half Moon Hotel, a sixteen-story buff-brick building fronting the boardwalk ten blocks west of the arcades and amusement rides. Military doctors had recently screened a batch of draftees for gonorrhea and nearsightedness. The recruits had pressed their inked thumbs to paper and affirmed their attraction to girls. Nicholson arrived shortly after dawn that Wednesday morning to see the men off to boot camp. They would muster at 8 a.m. or so beneath murals of Spanish ports in the hotels Galleon Grill, then leave for Grand Central Terminal.

Nicholsons window overlooked the gravel roof of the hotel kitchen annex. After settling down at his desk he noticed an unmoving figure lying on the gravel. He called the hotel operator and asked her to connect him to the eleventh-floor office of Alexander Lysberg, the night hotel manager. Something has happened, Nicholson told him.

What is it? Lysberg said.

I cant tell you over the phone, Nicholson said.

Lysberg rode an elevator downstairs. When he entered the draft-board office Nicholson gestured to the window. Sprawled like a rag doll on the kitchen roof lay the body of a hairy, thickset man. His rubbery lips were agape, revealing a lolling bovine tongue. His beefy left cheek was imprinted with roof deck gravel. The impact of the fall from his sixth-floor room, number 632, had split the crotch of his dark suit pants. His white button-down shirt lay open to the waist. His eyes stared unblinking into a clouded Brooklyn sky. Two knotted strips of white bed sheet fluttered at his side.

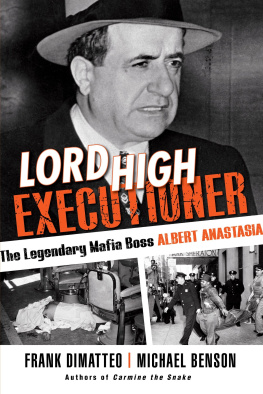

Even from a distance the two men recognized the body. Thirty-five-year-old Abe Reles, kinky-haired and jut-jawed, had served for a decade as the assassin-in-chief for an underworld death squad loosely known as Murder, Inc. When the principals of a coast-to-coast organized crime network identified an informant in their ranks, or a foot soldier who breached their loyalty code, they passed a murder contract down to Reles, who either took up his weapongun, garrote, ice pickor, more often, delegated the job to lieutenants. A veteran detective called them probably the worst ring of killers in American history. Their victims died horrible deaths, gangster deaths. They dumped bodies like garbage in shallow lime pits or left them doubled-up and decomposed in the trunks of cars abandoned on lonely streets.

Dead men could not testify: such was Reless lurid strategy. The tactic worked for a decade. Then, in February 1940, Reles abruptly turned against his lifelong friends and closest compatriots in crime. He abandoned his career as an underworld assassin to become an informantthe most talkative and damning in mob history. In a series of marathon meetings conducted over coffee and sandwiches in the district attorneys offices on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Municipal Building, he disclosed to prosecutors the vast and intricate workingsthe grudges and revenge, alliances and betrayalsof an elaborate criminal underground, a country-within-the-country, that law enforcement had previously only glimpsed in isolated pieces. Reles revealed another America hidden in shadow with its own banks and penal system, its own tax code and law enforcement.

The history of organized crime had been written over the decades in increments based on court appearances and police logs. Now, for the first time, heroes and villains, potentates and snitches, were revealed in a single dark opera told with flourish by a key player.

Speaking like a streetwise stand-up comic, Reles confessed to eleven murders. He resolved several dozen more, including deaths unknown to the police. He brought all the dirty work out into the light with the relish of a natural storyteller. He recalled with cinematic detail victims hatcheted, cudgeled, set on fire, trussed and dumped in peaceful upstate lakes, macerated by bullets, and, in at least one case, buried alive. His accounts were almost too gruesome to be real.

Reles made vivid for prosecutors the whole sweeping epic of life and death in the mob, mostly in Brooklyn, but as far afield as Miami and Los Angeles. After two decades of dodging and defying the law, he lifted the lid for the first time on an entire underworld, with all its thuggery and casual cruelty.

Reles was the keystone, the Jenga piece, in a government push to end once and for all the mobs long-reaching free hand in murder, racketeering, extortion, loan-sharking, drug smuggling, prostitution, and gambling. District attorneys waged their campaign to restore law and order, but also to advance themselves professionally. Whoever busted the mob would earn a path to higher office. The mobsters loss was the prosecutors gain.

In the months before he tumbled from that hotel window, Reles helped send four to the electric chair, including his two best friends. Now, in November 1941, the proceedings were poised to enter a weightier phase as prosecutors prepared to try the mob lords, men who would qualify for the Mount Rushmore of crime.

As the authorities battled to bring down the big bosses, the danger to Reles and other informants correspondingly intensified. It was known that the defendants or their allies still at large would try to arrange for Reles to die before he testified against them, before he could send them to the Sing Sing death house. Newspaper readers held their collective breath, waiting to see if layers of police protection could hold against the gathering forces of underworld revenge. Reles himself had told prosecutors that mob law decreed that the squealer must die.