The story of the Fall Creek Massacre could not have been written without the assistance of many individuals and institutions. I owe special thanks to the following: Professors J. Douglas Nelson and Carl Caldwell of Anderson University; Janet Brewer, Jill Branscum and the staff of the Nicholson Library at Anderson University; Indiana Historical Society Press editors Paula Corpuz, Kathleen Breen, and Ray Boomhower, and the staff of the Indiana Historical Society library, for their assistance in navigating through the Societys rich collection; Andy Hite, the site manager of John Johnstons estate at the Piqua Historical Site in Piqua, Ohio, who generously shared his time and insight into Johnstons career; the staff of the Ohio Historical Society at Columbus; Beth Oljace and the staff of the Indiana Room at the Anderson Public Library; Drew Wilson, whose paper in my Historical Inquiry class first drew my attention to the Fall Creek Massacre; Marcia Martin Murphy, whose comments reshaped and improved many aspects of the finished work; the staff of the Indiana State Archives in Indianapolis; the staff of the Indiana State Library; and the faculty of Anderson University, who provided financial support in a faculty development grant, a Falls Fund Distinguished Scholar grant, as well as a sabbatical leave of absence to complete the writing of the manuscript.

Introduction

My conclusions have cost me some labour from the want of coincidence between accounts of the same occurrences by different eye-witnesses, arising sometimes from imperfect memory, sometimes from undue partiality for one side or the other.[]

Thucydides

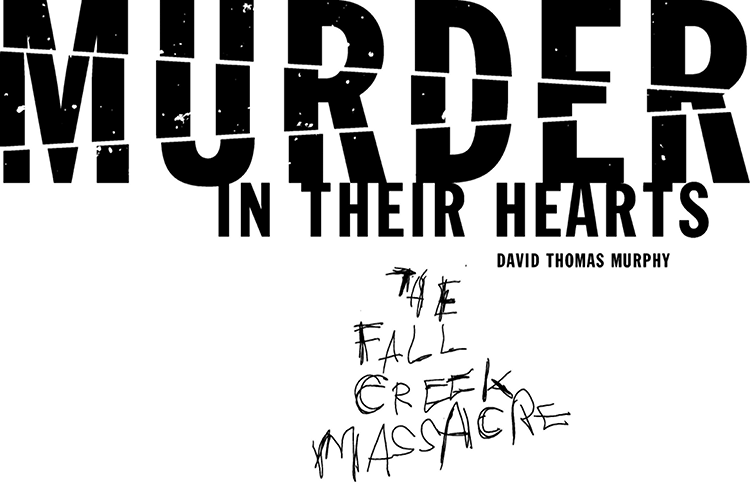

In the first six months of 1825, three white men were sentenced to death and hanged in Madison County, Indiana. During the previous spring, the trio had incited a gang of angry settlers to the premeditated murder of nine Indians camped along a tributary of Fall Creek where it flows through the county. At the time, the killings and the executions that followed sparked a national sensation. The slaughter in the soggy Indiana creek bottoms created a short-lived but serious national security crisis, and the affair retains a significance that transcends the local.

General histories of the pioneer era, when they note the Fall Creek Massacre at all, usually do so only in passing, although some appreciation of the massacres legacy lives on in central Indiana. These incidents once inspired a novel by Jessamyn West, an Indiana Quaker. The living history museum at Conner Prairie, near Indianapolis, sometimes stages trial reenactments for the benefit of students and local history buffs. Motorists passing through rural Madison County near the village of Markleville can still find a weathered bronze historical marker on the north shoulder of Indiana State Road 38, a long mile of cornfields, creeks, and woods southeast of the massacre site.

But the events at Fall Creek merit a larger place than they are typically accorded in the national memory of the era as well.[] Quite apart from any deeper historical significance, the dramatic story of that bloody spring remains gripping in and of itself. The carnage perpetrated by the white settlers, recounted in lurid detail in the contemporary press, retains a shocking impact into the present day. And, while violence between settlers and Native Americans was not unusual in the Old Northwest Territory during the early nineteenth century, this particular incident provoked a fateful and most unusual reaction. White men responsible for the outrage were singled out and hunted down, brought to trial, convicted by a jury of their neighbors, and, for the first time under American law, sentenced to death and executed for the murder of Native Americans.

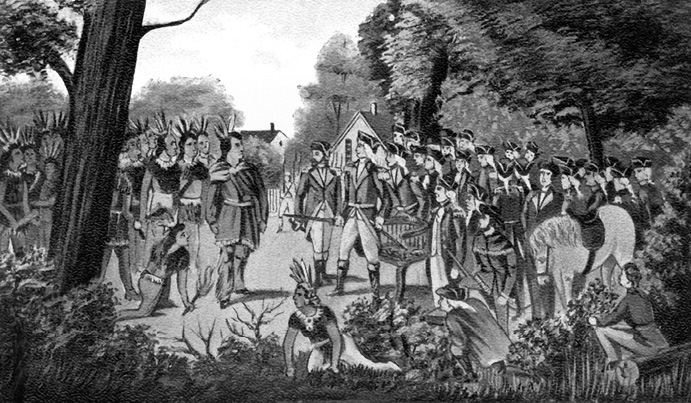

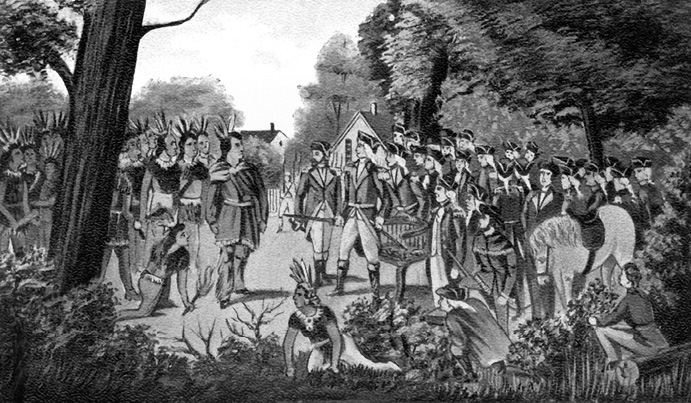

Between 1803 and 1809 Indiana territorial governor William Henry Harrison negotiated a series of land-cession treaties that opened the territory to settlement, causing unrest among the Native Americans. In 1810 Tecumseh warned Harrison against further land cessions, noting you have taken our lands from us and I do not see how we can remain at peace with you if you continue to do so. (Indiana Historical Society)

Those murders, and the subsequent executions, are also edifying for the student of history, and of American history in particular. There may be few historically verifiable incidents that remain more closely veiled in the fog with which time and frail human memory surround our past. Madison County lost its first courthouse (it is now on its third) to fire in 1880. Documents relevant to the accurate imposition of land taxes miraculously survived, but the blaze appears to have destroyed most of the early court records, including the original transcripts of the Fall Creek trials.

Information on the murders and their aftermath must be culled from a few surviving, mostly incidental sourcesfragmentary redactions of the legal proceedings, one published confession, a bare handful of dubious newspaper articles, scanty official correspondence, and the faulty memoirs set down decades later by participants in and witnesses to the proceedings. These have left a maddeningly blurred and ambiguous record. What historian Carl Waldman noted of Native American history in generalhearsay and legend play a part in what has been passed down. Contradictions abound.finds in this case a vivid specific instance.[]

What, exactly, happened at Fall Creek? That depends upon whom you ask. Beyond the elementally irreducible fact of violent death, virtually every meaningful aspect of the answer is subject to dispute. Did nine, or did ten, Indians inhabit the camp that was attacked? Were they mixed-race, Shawnee, Miami, Seneca, Delaware, Wyandotte, or even, in the case of one victim, white? Were five, six, or seven white men in the group that raided the camp and killed its inhabitants? Which of the murderers killed which of the victims? What did the accused murderers say, and what did local inhabitants and state officials do in response to the killings?