also by beverly lowry

fiction

Come Back, Lolly Ray

Emma Blue

Daddys Girl

The Perfect Sonya

Breaking Gentle

The Track of Real Desires

nonfiction

Crossed Over: A Murder, a Memoir

Her Dream of Dreams:

The Rise and Triumph of Madam C. J. Walker

Harriet Tubman: Imagining a Life

Who Killed These Girls?

The Unsolved Murders That Rocked a Texas Town

this is a borzoi book

published by alfred a. knopf

Copyright 2022 by Beverly Lowry

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

The photographs on appear courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lowry, Beverly, author.

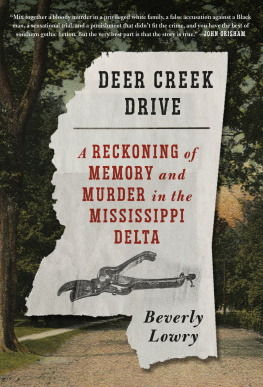

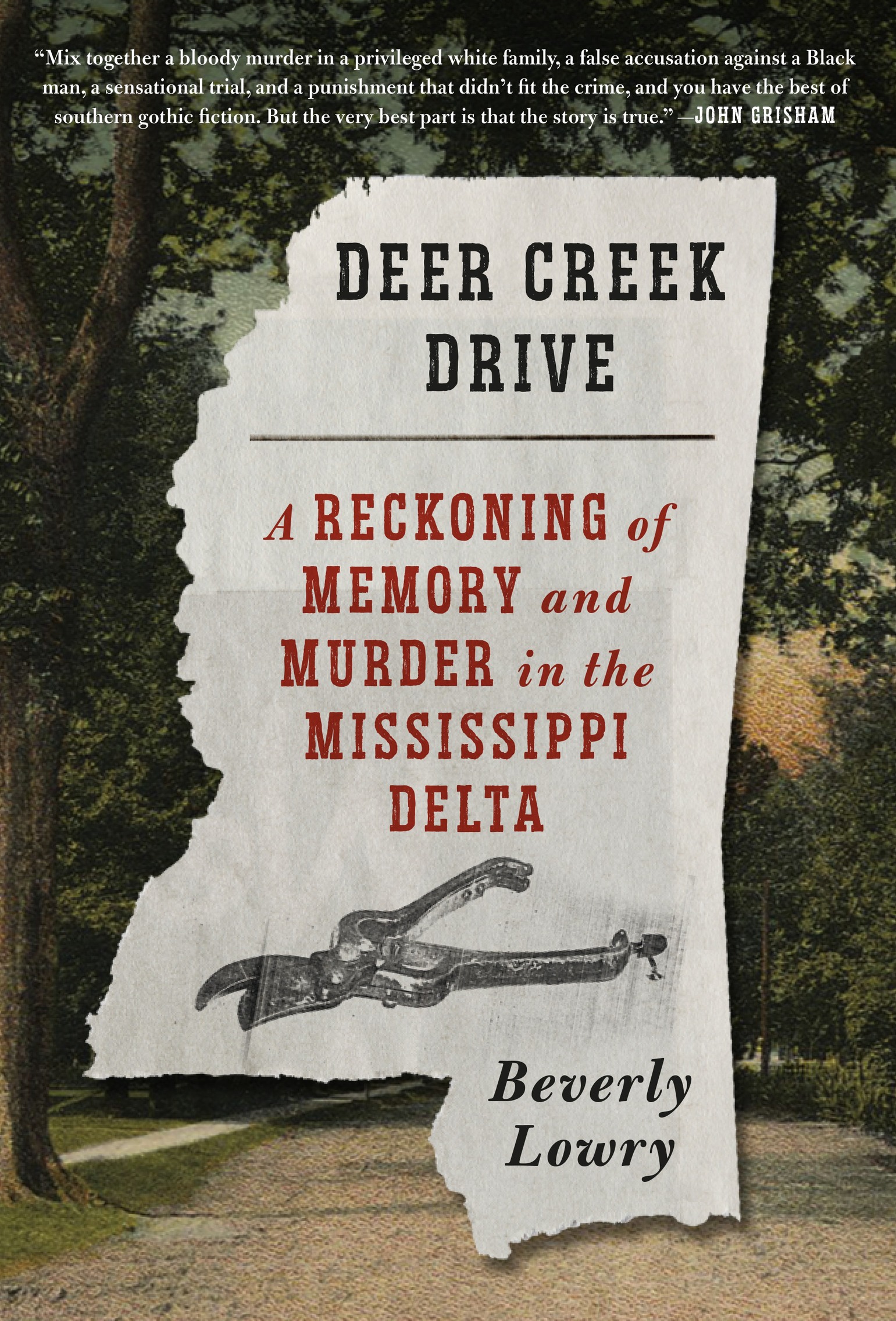

Title: Deer Creek Drive : a reckoning of memory and murder in the Mississippi Delta / Beverly Lowry.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021053204 | ISBN 9780525657231 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525657248 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Thompson, Idella, 18791948. | Dickins, Ruth Thompson, 19061996. | MurderMississippiLelandCase studies. | Leland (Miss.)Social conditions20th century. | Leland (Miss.)Race relations.

Classification: LCC HV6534.L45 L69 2022 | DDC 364.152/30976242dc23/eng/20211227

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053204

Ebook ISBN9780525657248

Cover images: (pruning shears) Tragedy-of-the-Month, 1949, Triangle Publications, Inc.; (background) Special Collections, University of Mississippi Libraries

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

ep_prh_6.0_140605063_c0_r0

For Greenville friends, past and present.

In Memory: Julia Reed

Rabbit Jenkins

Leila Wynn

Charlotte Buchanan

My parents.Their dreams.

Contents

Deer Creek Drive is, fundamentally, a story about the attitudes, behavior, and language of Mississippi in the 1950s. This was the decade of Brown v. Board of Education, of Emmett Till, and of the beginning of the end for Jim Crow. While this material is often difficult, my aim was always to illuminate and reckon with the reality of living and growing up in that section of the state we called the Delta during this time. As such, the book uses a number of primary sourcesdocuments, court testimony, newspaper articlesas well as a reliance on memory, much of which reflects the demeaning and problematic language that was used so freely and unsparingly at the time. It is both my story and the story of an unreconstructed South and how both of us were destined to change.

Beverly Lowry

I

The Crime

Known as States Exhibit No. 1, this is the architectural rendering of Idella Thompsons home in 1948, which was presented to the jury on the first day of the trial by the district attorney, Stanny Sanders. It is the only exhibit included in the digitized transcript of the trial and as such provides a kind of map to the crime and its aftermath, showing how big the rooms were and where they were located, how close the bathroom was to the back porch, how far the front door was from the crime scene, and other crucial details. It was reprinted in newspapers and in the tabloid magazine Tragedy-of-the-Month and is the kind of site-setting evidence lawyers like to come up with before anything else.

Looking Back

Youd think by now people would have forgotten or perhaps decided simply to let go of the memory of what happened in the Mississippi Delta town of Leland in the early afternoon of November 17, 1948. But nobody has. Even people too young to remember know about it. Theyve seen clippings pasted in old scrapbooks or heard the story (which did not, by the way, end that year or the next but went on and on, one of those stories that because people love to tell it keeps starting over). Although some local residents still refuse to engage, even briefly, in a discussion of the matter, there are those who wouldif you went to Lelandgladly point out the house where it happenedstill standing, freshly painted perfectly white, lawn exquisitely maintained. They might even be willing to tell you exactly where in the house the sixty-eight-year-old society matron was attacked, first in the enclosed back porch, and then dragged on a small rug into her own bathroom, where she, or, more than likely, her body, ended up: facedown, her daughter said, in her own blood soup, the crown of her head against the tub, beside which sat an ordinary three-legged wooden stool. And between the stool and her head, the gleaming nightmare weapon washed and wiped clean of prints and gore.

That it happened was shocking enough on its own. But there? In that neighborhood?

Until that year, both of these women, the society-matron mother and the socialite daughter, had lived pretty much their whole lives on this street, whichit is important to notewas and still is the most desirable in town, the street about which locals say, If you want to get to heaven, you have to live on Deer Creek Drive.

Or, as some would say, simply the Drive.

If by happenstance you did find yourself in Leland standing before the murder house, you might then want to check out the house where the dead womans daughter lived with her cotton broker husband and two young daughters: a mere three houses away down the Drive, north toward Stoneville. You could walk there in minutes, noting as you went, thanks in great measure to the Leland Garden Club, the beauty of the surroundings: the meandering creek to your left and on its high, sloping banks the oak and sycamore trees, the occasional surviving sweet gum, the crepe myrtle and pecan, the azalea and rosebushes, the park benches, the well-fed families of proprietary ducks.

That the two womens homes were situated on what some Leland families consider the wrong side of the creek should also be noted. It is, of course, a measure of small-town snobbery that there exists, to some, a bad side of the best street in town, but the distinction is also significant in terms of current property values. Houses on South Deer Creek Drive, according to a longtime realtor and lifelong resident, command a higher price. Asked why this was, she answered with a sigh, as if the reason should have been obvious. Because, she said, Black people live on the south side.

Close to? Or on?

These days? Both.

It was 2018. Id returned to the Delta to participate in the annual Hot Tamale Festival, which took place in downtown Greenville. The realtor was driving me around Leland, pointing out places of historical interest, including a museum devoted to Kermit the Frog and his creator, the puppeteer Jim Henson, surely Lelands best-known resident, more famous even than the bluesmen James Son Thomas and Johnny Winter. Shed promised to get me into the murder house, which shed personally sold five times since the killing, but when we drove there and she went inside to ask, the current residents told her no way.