Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

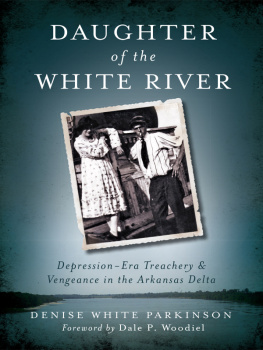

Copyright 2013 by Denise White Parkinson

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.013.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Parkinson, Denise White.

Daughter of the White River : Depression-era treachery and vengeance in the Arkansas Delta / Denise White Parkinson ; foreword by Dale Woodiel.

pages cm

Summary: A true crime narrative about the life and misdeeds of Helen Spence in Arkansas during the Depression--Provided by publisher.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-913-6 (paperback)

1. Spence, Helen, 1912?-1934. 2. Women outlaws--Arkansas--Biography. 3. Outlaws--Arkansas--Biography. 4. Female offenders--Arkansas--Biography. 5. Betrayal--Arkansas--Case studies. 6. Revenge--Arkansas--Case studies. 7. Women prisoners--Arkansas--Biography. 8. Escapes--Arkansas--History--20th century. 9. White River Region (Ark. and Mo.)--Biography. I. Title.

HV6248.S6147P27 2013

364.1092--dc23

[B]

2013030786

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my children: Jasper Williams, Grace Norton and Cason Parkinson.

Love is real, not fade away.

the tragedy began

With Homer that was a blind man,

And Helen has all living hearts betrayed.

W.B. Yeats

Contents

Foreword

Although black-and-white box cameras were common in the 1930s even in relatively isolated river communities like Crocketts Bluff, it would have hardly occurred to someone to make a picture of the five or six houseboats moored (or tied up) along the mile or so bank of the White River between the bluffs themselves and the next bend to the north just past what I recall as a favorite sandbar for swimming in the late 1940s.

The Woodiel house rested on a modest rise above the bluff overlooking the river, but many of my parents friends lived literally on the river in houseboats, which generally floated on great logs. Among my earliest childhood memories is a visit to the houseboat of Mr. and Mrs. George Gosnell, during which time Mr. Gosnell, to my great delight, allowed me to choose an apple from a large barrel-like container. Years later, the Gosnells moved to a house on land a few hundred yards northward up the riverbank across from the Marrs family.

There was another occasion, when I accompanied my father on a winter afternoon visit, during which he and Mr. Gosnell smoked corncob pipes filled with raw tobacco roughly ground from complete tobacco leaves that I believe he ordered by mail from Kentucky. Although the fumes from their pipes brought tears to my youthful eyes, the stories they exchanged made it worth the discomfort.

It might well have been on such a visit that I first heard the taleat the time still fresh in the minds of river folksof a woman who went right into the DeWitt Court House and shot a man dead before she was sent to prison and later killed trying to escape.

The details as well as the sentiments of this story were renewed afresh when I received a request from Denise Parkinson to use a watercolor image of a houseboat from the Crocketts Bluff website, which Ive nurtured for the past few years, devoted to the preservation of the culture of this place along the river where I was born. Our correspondence revealed her plans for Daughter of the White River, the focus of which is Helen Spence, the woman of the tale from my childhood.

Stories emerge from generation to generation the way wildflowers burst forth season after season without any special consideration from those who are stunned by their seasonal emergence. So it is with the stories that continue to emerge from the culture that thrived along the lower White River in Arkansas during the 1920s and 30s, when the area was alive with communities of families. The river was their fundamental life source, a world whereby through hunting, fishing and mussel shelling they sought and secured their livelihoods from year to year, generation to generation.

As Parkinson reveals in this sensitive and enlightening recollection of one of its major legends, it was an isolated and independent world with its own sense of community and its own concepts of love, responsibility and justiceessentials of all enduring cultures.

Ancient verities worthy of our consideration in any season.

DALE P. WOODIEL, 2013

West Hartford, Connecticut

Preface

I first wrote about my childhood memories of the White River more than a decade ago for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette newspaper. The short piece provided filler for a weekend section in the promotions department where I was employed as an editor.

I had traveled to the upper reaches of the White River, to the tiny town of Possum Grape, by way of even tinier Grande Glaise (or the other way around) for a separate feature story. Some nice folks showed me staggering piles of mussel shells left over from early twentieth-century button factories. They also brought out a collection of nineteenth-century French coins excavated from the riverbanks. Grande Glaise is named for its fine clay, dug and exported by long-ago French explorers.

I wish I had a copy of what I wrote then. The pages got lost along the way. My journalistic efforts and travels compose a disappearing study of vanishing customs, artifacts, people and places. This sympathy began when I witnessed firsthand the loss of our family home (actually an ancient houseboat situated on land) and property on the banks of the White River, a river I initially thought was named after our family (the Whites) due to the logic of childhood.

Our summer place near Clarendon was where I saw, up close, my first cicada and alligator gar. Food tasted better there; sleep was deeper. I heard my first ghost story there, sitting around the campfire listening to my father and grandfather describe mysterious lights on the river that followed them one night when they were running trotlines. Our summers on the White came to an end in the late 1960s when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers suddenly and arbitrarily manipulated the rivers water level.

On the subject of the Army Corps of Engineers that built the Dam that caused the change in water levels of the White River and subtracted the home and summers of living outdoors, fishing every day and generally enjoying everything, my father could rage and sometimes did. But the damage was done. The old homeplace was underwater. And no amount of car trips to randomly identical Official Arkansas State Park campsites, with their concrete picnic tables on slabs and tents like refugee camps beside murky lakes trapped behind cement wallsnone of the manufactured Great Outdoors could atone for the loss, a loss that over time went unspoken. (Clarendon, I knew thee not.)

This catalogue of loss multiplied throughout families like ours who had, for generations, kept houseboats, hunted and fished, never bowing to overseer or landlord. The numbers of people forced off the White River swelled, marking the disintegration of community across an entire region. Sons, daughters, siblings and cousins dispersed, moving away from one another and the river, away from land and family at an equal pace of subtraction.

Next page