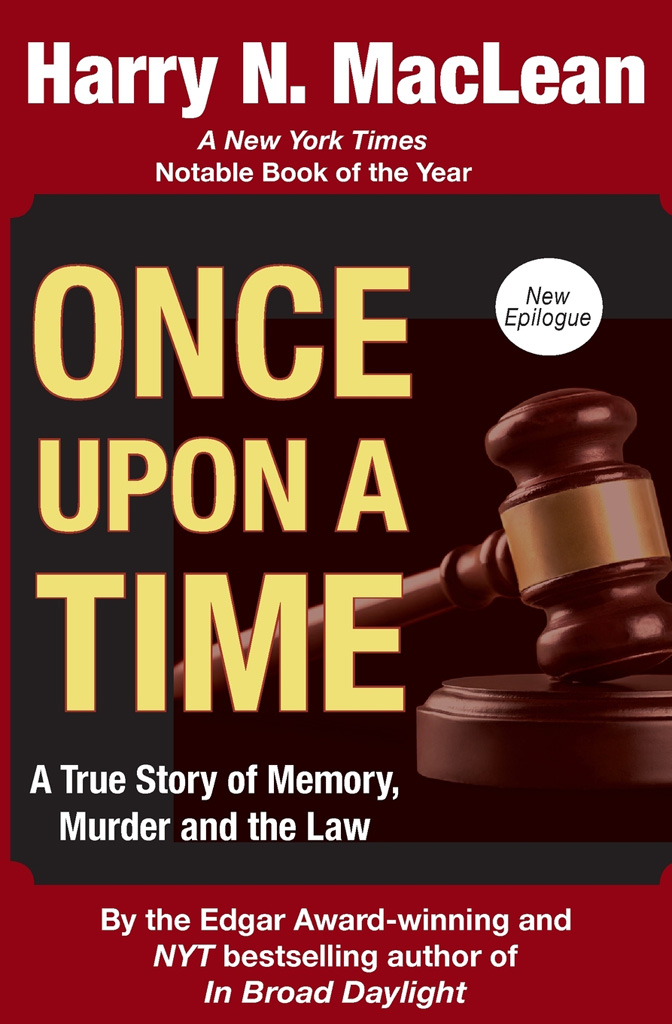

Harry N. MacLean

Copyright 1993 Harry N. MacLean

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ISBN: 978-1-0878-8676-3

ISBN: 978-1-7371-3941-6 (e-book)

For Mike and Pat MacLean,

Keepers of a Safe Harbor.

ALSO BY HARRY N. MACLEAN

In Broad Daylight

The Story Behind In Broad Daylight

The Past is Never Dead

The Joy of Killing

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN ONE SENSE THIS BOOK IS ABOUT THE MURDER OF A LITTLE GIRL IN Foster City, California, in 1969, and the trial of her alleged murderer in Redwood City in 1990. In a much larger sense this book is about the nature of human memory, an elusive and still little understood function of the mind. The effect of trauma on the memory process, particularly in a child, and the ability of the mind to isolate the trauma are key themes because the murder charge is based on a memory supposedly repressed for twenty years. The tendency of the personality to repeat and reenact childhood traumas is a theme woven inextricably into the search for the truth in the trial of the alleged murderer.

In coming to understand the various processes and dynamics of the mind, I spoke with many psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other professionals in the mental health field, to whom I am greatly indebted. I would particularly like to mention Dr. Stephen White, an author and clinical psychologist in Boulder, Colorado, whose contribution to this book, both as a friend and a professional, is immeasurable. His ability to translate psychiatric concepts and jargon into understandable terms and bring them to bear on the facts of this story was invaluable, as was his support during the long journey of researching and writing this book. I am also grateful to Dr. Michael Weissberg, an author, psychiatrist, and member of the faculty of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, for his suggestions and wise counsel.

I would also like to thank Cinde Chorness, a San Mateo reporter, who shared her insights and knowledge unstintingly and who contributed to the development of the manuscript in countless ways. Without her unrelenting encouragement and support, I could easily have wandered off to a less difficult and challenging story. Her name might well belong on the jacket of this book.

HarperCollins was kind enough to hire Alice Price, a Denver freelance writer and editor, to edit the manuscript. Alice did a masterful job of straightening out some serious kinks, relocating stray scenes, fixing bad grammar, and persuading me to cut several beloved, but fanciful, paragraphs.

I would also like to thank Neil Chetik for his valuable research assistance; Suzanne Snider for her secretarial and administrative support; Diane Gonzolas for her editorial suggestions; and Tom Austin and Jean Obert for once again allowing me to live and write in their beautiful house on Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii.

I hesitate to list the contributions of many of the individuals whose stories are told herein, but obviously many of them gave generously of their time and energy, for which I am extremely grateful.

Finally, thanks to my mother and father and a blessing on the spirits of Jules Roth, a friend and healer, and Sharon Galleher, my sister and guide.

An asterisk (*) indicates the use of a pseudonym.

Part One

CHAPTER 1

September 1989

Mary Jane Larkin stood at the front of the classroom and looked out at the sea of small faces staring up at her. Her hands rested lightly on her wooden desk, the same one she had used for the past twenty-five years in teaching fourth and fifth grades at Foster City Elementary School. Next to her hands lay her open grade book, with the students' names neatly printed in ink in alphabetical order, and pencils, bottles of glue and stacks of paper.

Things had changed over the years at the schoola lot more Asian faces filled her classroom nowbut some things remained the same, like the row of black iron coat hooks on the back wall and the small metal desks with the wooden lift-up tops which had been in her classroom when she started almost a quarter of a century earlier. Her students today were certainly more sophisticated, with cable television and home computers, but they were still kids, innocent and unwary. You couldn't tell them often enough about strange men in unfamiliar cars with open doors and dolls on the front seat and what might happen if they got too close. Fourth- and fifth-graders had brief attention spans and short memories, and they still believed that the world was a safe place. There was one way, a way she had used at the beginning of every class since 1970, to convince them otherwise. What had happened in the fall of 1969 had ripped the veil of innocence from everyone's eyes. Although reliving that time brought back many of the horrible feelings, it was the best way she knew to make sure it didn't happen again. Mrs. Larkin closed her attendance book and pulled herself together to tell them the story.

"Many years ago I had a girl in my class who disappeared," she began, thinking back on the time when Foster City was a small, isolated community. Only one neighborhood had existed then, and it was populated by young families with lots of children and mothers who stayed at home and kept house and greeted their kids after school with a snack. Life was simpler and safer; kids either walked or rode their bikes to school, and in the afternoons they played at each others houses or in the vacant lots until dinner time. Mary Jane Larkin had two children herself, and while she had reminded them often about strangers, she worried more about them getting sick or falling off the bars on the playground. It wasn't like that anymore, of course; in the past eight or nine years it seemed that missing children on the peninsula had become almost commonplace.

"Her name was Susan Nason," she continued, "and they found her two months later, kidnapped and murdered up by the reservoir." Susan had been so frail, so small, there just didn't seem to be much to her. But with her blue eyes and reddish hair cut in bangs and pulled back from her ears, she was a bubbly and lively child. Mary Jane had never forgotten Susan, not in all these years. Back then there was no grief counseling for students or teachers after a tragedy and everybody just dealt with it in their own way. "School must go on," had always been her attitude, and she had come to class smiling and cheerful.

"Now I don't want to scare you ..." she insisted to her students. "This is a safe community and you all come from nice homes and loving parents." The tiny community had changed after Susan disappeared. The children no longer walked to school with friends; parents either walked or drove them in the morning, and at 3:00 P.M. the adults would be bunched up outside the door waiting to pick them up.

But her fourth-graders hadn't really reacted to the tragedy, at least not in an obvious way, even after Susans body was found. Mary Jane didn't mention Susan to her students and they didn't ask about her. Children at that age didn't quite grasp the meaning of death. They may have understood that Susan wouldn't be at school that day, or the next, but not that she would never be anywhere again.