ALSO BY RICHARD KLUGER

History

Simple Justice:

A History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black Americas Struggle for Equality

The Paper:

The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune

Ashes to Ashes:

Americas Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris

Seizing Destiny:

The Relentless Expansion of American Territory

Novels

When the Bough Breaks

National Anthem

Members of the Tribe

Star Witness

Un-American Activities

The Sheriff of Nottingham

Novels with Phyllis Kluger

Good Goods

Royal Poinciana

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Richard Kluger

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kluger, Richard.

The bitter waters of Medicine Creek : a tragic clash between white and native America / Richard Kluger.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59534-8

1. Nisqually IndiansHistory19th century. 2. Nisqually IndiansGovernment relations. 3. Leschi, Nisqually chief, d. 1858. 4. Leschi, Nisqually chief, d. 1858Trials, litigation, etc. 5. Stevens, Isaac Ingalls, 18181862. 6. Puget Sound (Wash.)History19th century. I. Title.

F 99. N 74K55 2011

979.7004979435dc22 2010034249

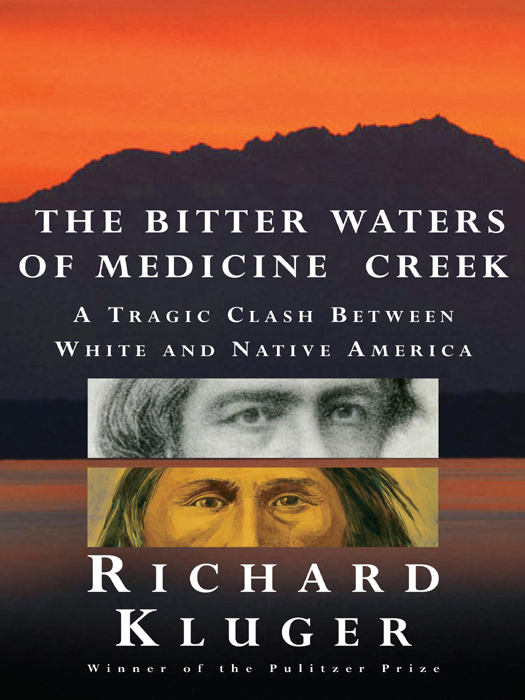

Jacket images: (background) Puget Sound and Olympic Mountains, Washington, U.S. UpperCut Images / Alamy; (insets, top to bottom) Brigadier General I. Ingalls Stevens by Joseph E. Baker, J. H. Buffords Lith., Boston, MA, 1861 (detail), Washington State Historical Society; Chief Leschi, Nisqually by Raphael Coombs, 1894 (detail), Washington State Historical Society Jacket design by Chip Kidd

Maps by Darin Jensen

v3.1

For Adrianne and Mike

warm, wise, witty,

and ever venturesome

LISTEN

Once people could see beyond space

And watch the eagle fly toward the sun.

Power is coming back to you.

Youve been looking down,

Now its time to look up.

The spirit warms the blood

And electrifies the heart.

Like spring coming out of winter;

Like a boy learning to ride,

Or a young hawk wavering

Across the sky.

Songs will be heard by those who listen.

People are chanting;

Something bigger is coming,

Of dreams promised long ago.

A new song is heard.

People will find unity,

For the Lord nourishes all.

He speaks to all people.

Jack Iyall

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A Fresh Reckoning

A FEW YEARS BACK , I was casting about for an appealing subject on which to base a historical novel, a genre in which I had published three earlier works. In both my fictional writing and my books on American social history, I had dwelled frequently on the law and its majesty along with its debasement by malpractice and misapplication. And so it occurred to me that a stirring narrative could be crafted dealing with the adventures of a fictional circuit-riding judge during the frontier days of the Old West, when life brimmed with peril and where the line between virtue and villainy at times grew indistinguishable.

Hoping to blend literary license with historical authenticity, I needed to discover at the outset whether legal documents have survived from that earlier timein particular from the territorial era before states were carved from vast expanses of wilderness, where the law was largely an abstract premise, heeded fitfully and enforced haphazardly if at all. Research on an earlier book had taught me that Washington, before it was granted statehood in 1889, had been a U.S. territory for thirty-six yearslong enough to have generated a considerable record of rough-and-ready jurisprudence, assuming the authorities had taken the trouble to preserve it. I phoned the state law library at the Temple of Justice, as Washingtonians, with admirable reverence, have named their Supreme Court building in Olympia, the state capital, and spoke with a pleasant and cooperative librarian.

Oh, yes, she said, we have all the opinions of the court from the territorial periodand theyre all available online. And she gave me the Web link.

I thanked her with anticipatory glee.

You might, my librarian friend added a bit tentatively, want to have a look at case number three in the first volume of the territorial reports.

Because ? I asked.

It was the first capital case in the history of Washington Territory to be appealed to the Supreme Courtthat was the direct predecessor of our present State Supreme Court. The year, she said, was 1857.

I see, I said, not quite catching her drift. And was there something special about the case that I ought to ?

It dealt with a notorious murder conviction, said the librarian. And the decision was reviewed two years ago.

You meanthat would be, whatone hundred forty-seven years later?

Yes, she said and explained that a special tribunal had assembled, presided over by the current chief justice of the Supreme Court of the state of Washington, to reconsider the matter.

Recalling the laws hoary precept that justice delayed is justice denied, I ventured, Wasnt that a little late in the game?

She gave a pleasant laugh and urged me to check into the circumstances. And so I have.

What follows is not a historical novel but rather the story surrounding that case, Washington Territory v. Leschi, an Indian, an all but forgotten episode from our nations past, which occurred in a then remote but breathtakingly beautiful setting in the farthest northwest corner of the country. The very obscurity of these circumstances, I feel, invites cool reflection on the issue at its core instead of aversion from it as a too familiar and depressing eyesore on our shared cultural landscape. Call it a fresh reckoning.

I logged on to the site and read the courts 1857 ruling. Its first few sentences betrayed a transparently racist tone suggesting that something less than a disinterested quality of justice was about to be rendered. Events over the three years preceding the courts decision, my subsequent investigation led me to conclude, were shaped by a similarly phobic disposition among Washington Territorys citizenry at large. Why this should have been so is a question, I believe, worthy of consideration even at this seemingly late date. For we are still a young nation, and despite all our feats, our united prospects are likely to turn on our ability to learn from how we have erred as well as succeeded.

White Americans cannot deny their long history of abusive transactions with people of color. These offenses, it should be noted out of fairness, can be explained in part by the fact that no other sizable national state has ever been formed from the confluence of so many diverse ethnic streams. All our heterogeneous ferment no doubt made contentiousness inevitable. In retrospect, it is hardly surprising that whites would assert privileges of entitlement flowing from their fortunate economic status and social rank (also known as the accident of birth) and assign nonwhite minorities the status of a permanent servile class. And in accord with the precepts of Social Darwinism, this uncivil subjugation was facilely intellectualized as neither commendable nor reprehensible; it was merely human nature in the raw. Everywhere and always, the strong have dominated the weak, as with every species in the jungle and individuals within every social subset. No one said what emerged from the melting pot had to look, smell, or taste very good.