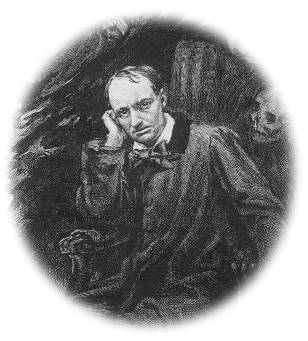

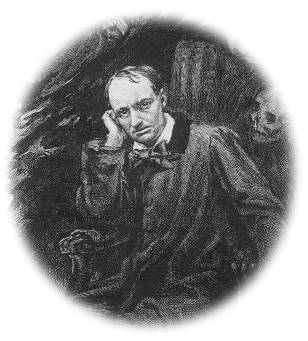

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse the entire series

Charles Baudelaire

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Charles Baudelaire - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 953 1

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

NOTE

When reading poetry on an eReader, it is advisable to use a small font size and landscape mode, which will allow the lines of poetry to display correctly.

The Poetry of Charles Baudelaire

Baudelaire was born in Paris on 9 April 1821.

Place Louis XVI, Paris, now Place de la Concorde by Giuseppe Canella, c. 1829

Rue Hautefeuille in c. 1869 Baudelaire was born in a house that no longer stands on this street.

The plaque commemorating the poets birth site

Brief Introduction: Charles Baudelaire by Henry James

From French Poets and Novelists, 1878

A S A BRIEF discussion was lately carried on touching the merits of the writer whose name we have prefixed to these lines, it may not be amiss to introduce him to some of those readers who must have observed the contest with little more than a vague sense of the strangeness of its subject. Charles Baudelaire is not a novelty in literature; his principal work dates from 1857, and his career terminated a few years later. But his admirers have made a classic of him and elevated him to the rank of one of those subjects which are always in order. Even if we differ with them on this point, such attention as Baudelaire demands will not lead us very much astray. He is not, in quantity (whatever he may have been in quality), a formidable writer; having died young, he was not prolific, and the most noticeable of his original productions are contained in two small volumes.

His celebrity began with the publication of Les Fleurs du Mal, a collection of verses of which some had already appeared in periodicals. The Revue des Deux Mondes had taken the responsibility of introducing a few of them to the world or rather, though it held them at the baptismal font of public opinion, it had declined to stand godfather. An accompanying note in the Revue disclaimed all editorial approval of their morality. This of course procured them a good many readers; and when, on its appearance, the volume we have mentioned was overhauled by the police a still greater number of persons desired to possess it. Yet in spite of the service rendered him by the censorship, Baudelaire has never become in any degree popular; the lapse of twenty years has seen but five editions of Les Fleurs du Mal. The foremost feeling of the reader of the present day will be one of surprise, and even amusement, at Baudelaires audacities having provoked this degree of scandal. The world has travelled fast since then, and the French censorship must have been, in the year 1857, in a very prudish mood. There is little in Les Fleurs du Mal to make the reader of either French or English prose and verse of the present day even open his eyes. We have passed through the fiery furnace and profited by experience. We are happier than Racines heroine, who had not

Su se faire un front qui ne rougit jamais.

Baudelaires verses do not strike us as being dictated by a spirit of bravado though we have heard that, in talk, it was his habit, to an even tiresome degree, to cultivate the quietly outrageous to pile up monstrosities and blasphemies without winking and with the air of uttering proper commonplaces.

Les Fleurs du Mal is evidently a sincere book so far as anything for a man of Baudelaires temper and culture could be sincere. Sincerity seems to us to belong to a range of qualities with which Baudelaire and his friends were but scantily concerned. His great quality was an inordinate cultivation of the sense of the picturesque, and his care was for how things looked, and whether some kind of imaginative amusement was not to be got out of them, much more than for what they meant and whither they led and what was their use in human life at large. The later editions of Les Fleurs du Mal (with some of the interdicted pieces still omitted and others, we believe, restored) contain a long preface by Thophile Gautier, which throws a curious side-light upon what the Spiritualist newspapers would call Baudelaires mentality. Of course Baudelaire is not to be held accountable for what Gautier says of him, but we cannot help judging a man in some degree by the company he keeps. To admire Gautier is certainly excellent taste, but to be admired by Gautier we cannot but regard as rather compromising. He gives a magnificently picturesque account of the author of Les Fleurs du Mal, in which, indeed, the question of pure exactitude is evidently so very subordinate that it seems grossly ill-natured for us to appeal to such a standard. While we are reading him, however, we find ourselves wishing that Baudelaires analogy with the author himself were either greater or less. Gautier was perfectly sincere, because he dealt only with the picturesque and pretended to care only for appearances. But Baudelaire (who, to our mind, was an altogether inferior genius to Gautier) applied the same process of interpretation to things as regards which it was altogether inadequate; so that one is constantly tempted to suppose he cares more for his process for making grotesquely-pictorial verse than for the things themselves. On the whole, as we have said, this inference would be unfair. Baudelaire had a certain groping sense of the moral complexities of life, and if the best that he succeeds in doing is to drag them down into the very turbid element in which he himself plashes and flounders, and there present them to us much besmirched and bespattered, this was not a want of goodwill in him, but rather a dulness and permanent immaturity of vision. For American readers, furthermore, Baudelaire is compromised by his having made himself the apostle of our own Edgar Poe. He translated, very carefully and exactly, all of Poes prose writings, and, we believe, some of his very valueless verses. With all due respect to the very original genius of the author of the Tales of Mystery, it seems to us that to take him with more than a certain degree of seriousness is to lack seriousness ones self. An enthusiasm for Poe is the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection. Baudelaire thought him a profound philosopher, the neglect of whose golden utterances stamped his native land with infamy. Nevertheless, Poe was vastly the greater charlatan of the two, as well as the greater genius.

Next page