Possess the Air

Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolinis Rome

Taras Grescoe

biblioasis

windsor, ontario

Copyright Taras Grescoe, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license visit

www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

first edition

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Possess the air : love, heroism, and the battle for the soul of Mussolinis Rome / Taras Grescoe.

Names: Grescoe, Taras, author.

Description: Series statement: Untold lives

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190119039 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190119276 | ISBN 9781771963237 (softcover) | ISBN 9781771963244 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Bagnani, Gilbert, 1900-1985. | LCSH : Bagnani, Stewart, 19031996. | LCSH : De Bosis, Lauro, 19011931. | LCSH : Political activistsItalyBiography. | LCSH : Anti-fascist movementsItalyHistory20th century. |

LCSH : ItalyHistory19141945.

Classification: LCC DG 556.A1 G74 2019 | DDC 945.091dc23

Edited by Janice Zawerbny

Copy-edited and indexed by Allana Amlin

Cover designed by Michel Vrana

Interior designed by Ingrid Paulson

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country, and the financial support of the Government of Canada. Biblioasis also acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council ( OAC ), an agency of the Government of Ontario, which last year funded 1,709 individual artists and 1,078 organizations in 204 communities across Ontario, for a total of $52.1 million, and the contribution of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates. This is one of the 200 exceptional projects funded through the Canada Council for the Arts New Chapter program. With this $35M investment, the Council supports the creation and sharing of the arts in communities across Canada.

For Victor,

who, from the get-go,

has known that

life is so great.

Minos may possess everything, but he does not possess the air.

Ovid, Daedalus and Icarus

The events described in Possess the Air begin in Italy one hundred years ago, when war, corruption, and economic uncertainty had shaken a peoples confidence in the fundamental institutions of democracy.

At a crucial time, Benito Mussolini rose to power by promising to make Italy great again. Before declaring himself dictator, though, Mussolini was democratically elected to the Italian parliament. His success was enabled by elitesboth Conservatives and Liberalswho chose to remain silent, or to maintain their power by cutting deals with a man they knew advocated division, winked at brutality, and exalted war. Mussolini became Il Duce because too many Italians undervalued the free institutions underlying the modern democratic stateinstitutions that previous generations had battled to establish and defend, often at the cost of their lives. The willingness to trade liberty for a spurious promise of security, prosperity, and glory allowed an opportunistic autocrat to implement the tenets of Fascism, an ideology that would visit unspeakable terror and bloodshed on Europe and the world.

Not everybody accepted Mussolinis vision of the future. Many Italians were willing to sacrifice their careers, their freedom, and even their lives to oppose the hate, violence, and warmongering they saw taking over the public life of the country they loved.

This is the story of how, in a period of rising authoritarianism, some patriots found a way to fight for the liberty that many of their fellow citizens had come to take for granted, or even spurn.

Which is what makes thisas the memory of the consequences of succumbing to the empty promises of a strongman appears to be fadinga story for our time.

Contents

Prologue

The View from the Janiculum

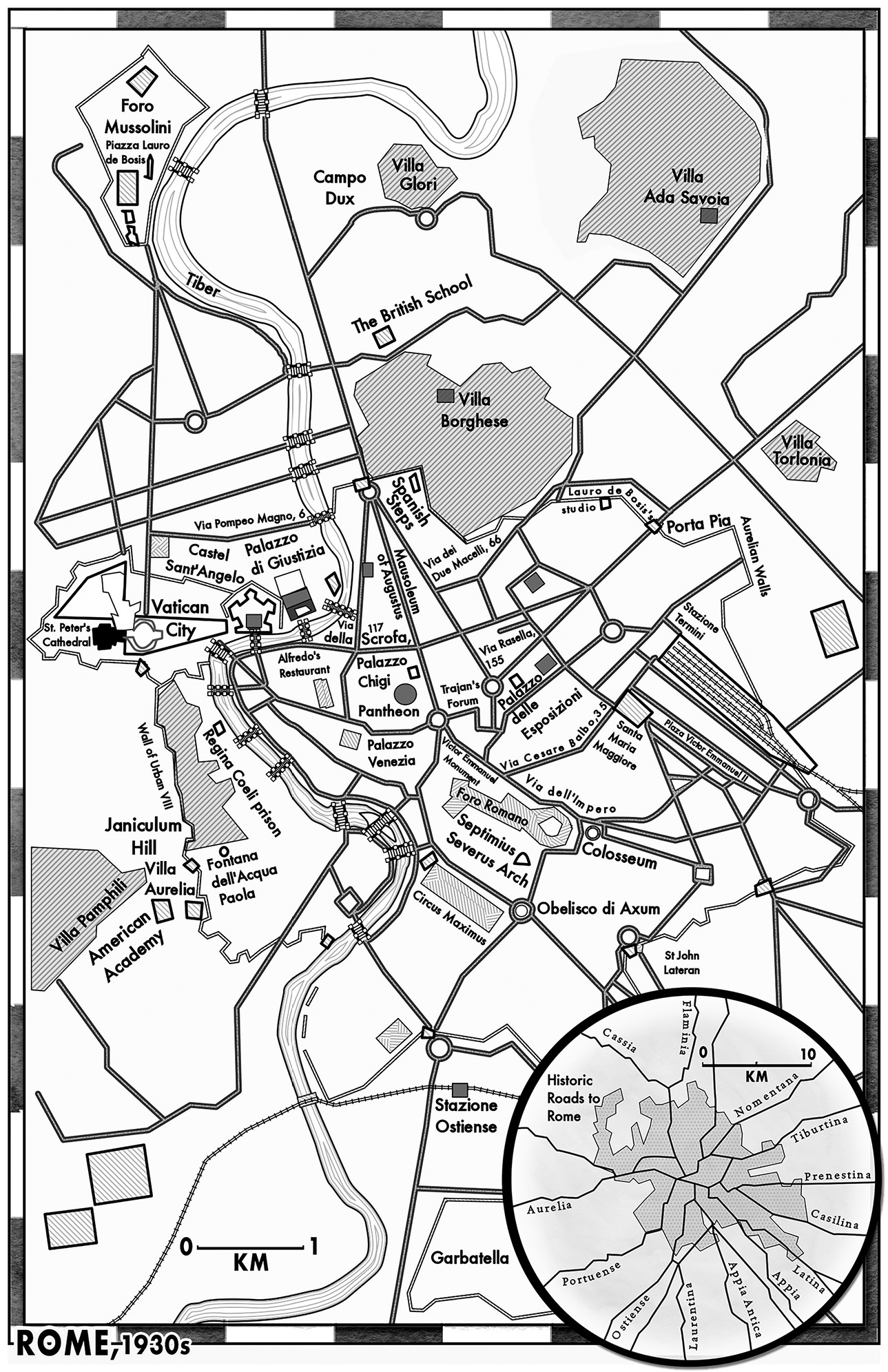

A lucky walker in Rome, weary of dodging gelato-eaters and rushing motorini, may be lured out of the teeming streets of Trastevere by the prospect of the upward-sloping paving stones of the sycamore-shaded Via Garibaldi. To the right, a side street dead-ends in flights of well-worn stone steps, bordered on one side by fortifications built by a third-century emperor to repel barbarous Germanic tribes.

The staircase ascends, alongside crumbling bricks overgrown with wildflowers and canary-grass, to a piazza dominated by a striking monument in luminous travertine limestone. The Fontana dellAcqua Paola is a confection of the high Baroque, built around five nichesdivided by columns of red granite and topped by high-perched griffins, lines of stone-cut Latin, and a gossamer iron crossout of which water gushes into a cerulean basin, as shallow as it is enticing. The pet project of a seventeenth-century Pope, it is fed by the same ancient aqueduct that once filled Trasteveres naumachia, the artificial lake where the Emperor Trajan staged mock naval battles using galleys rowed by real slaves. Taxi drivers know it simply as the fontanone, the big fountain.

The Fontana dellAcqua Paola, however, is merely the backdrop to a far more impressive spectacle. Crossing the paving stones of the semi-circular piazza, the fortunate stroller approaches a curved stone balustrade, which projects like a proscenium over the most sumptuous of playhouses. Just beyond the high canopies of thin-trunked umbrella pines, the first metropolis of the world unscrolls to the limits of peripheral vision.

Ecco: Roma.

In the foreground, quadrilaterals of weathered stucco in hues of ochre and pink form a Cubist jumble, jostling around the bend in the Tiber that snags Trastevere, the most ancient and authentic of Romes rioni, or central neighbourhoods, like a bishops crozier. Across the river, the hemispheric roof of the two-millennia-old Pantheon, the largest dome in the world until well into in the twentieth century, protrudes from Rococo cupolas, a concrete barnacle cemented fast to the medieval and Renaissance city. And, white as sun-bleached baleen, the Brescian marble of the Vittoriano, that pretentious monument to the earthiest of Italys kings, rises against the Impressionist smear of blue on the eastern horizon, the foreboding Sabine and Alban Hills.