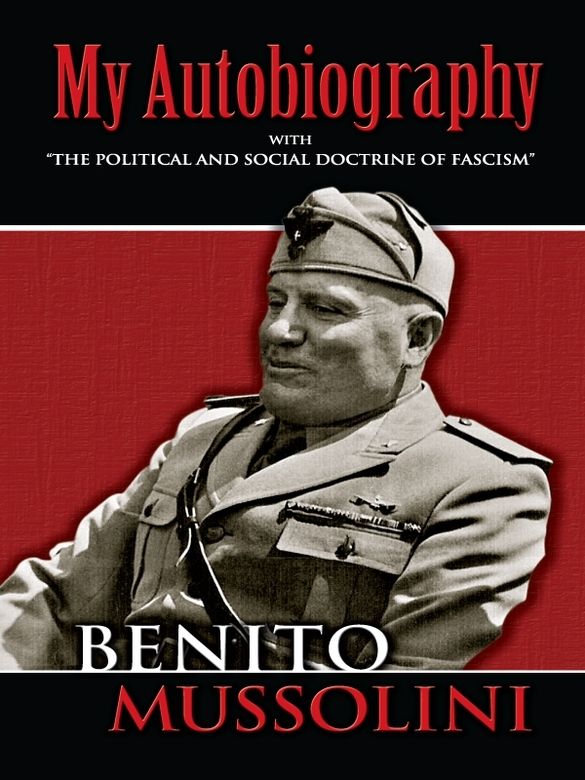

The Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism

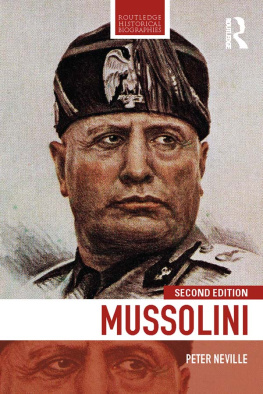

by Benito Mussolini

An Authorized Translation by Jane Soames

This is an authorized translation of an article contributed by the Duce in 1932 to the fourteenth volume of Enciclopedia Italiana. It is the only statement by Mussolini of the philosophic basis of Fascism.

WHEN, in the now distant March of 1919, I summoned a meeting at Milan through the columns of the Popolo dItalia of the surviving members of the Interventionist Party who had themselves been in action, and who had followed me since the creation of the Fascist Revolutionary Party (which took place in the January of 1915), I had no specific doctrinal attitude in my mind. I had a living experience of one doctrine onlythat of Socialism, from 19034 to the winter of 1914that is to say, about a decade: and from Socialism itself, even though I had taken part in the movement first as a member of the rank and file and then later as a leader, yet I had no experience of its doctrine in practice. My own doctrine, even in this period, had always been a doctrine of action. A unanimous, universally-accepted theory of Socialism did not exist after 1905, when the revisionist movement began in Germany under the leadership of Bernstein, while under pressure of the tendencies of the time, a Left Revolutionary movement also appeared, which though never getting further than talk in Italy, in Russian Socialistic circles laid the foundations of Bolshevism. Reformation, Revolution, Centralizationalready the echoes of these terms are spentwhile in the great stream of Fascism are to be found ideas which began with Sorel, Peguy, with Lagerdelle in the Mouvement Socialiste, and with the Italian trades-union movement which throughout the period 190414 was sounding a new note in Italian Socialist circles (already weakened by the betrayal of Giolitti) through Olivettis Pagine Libre, Oranos La Lupa, and Enrico Leones Divenire Sociale.

After the War, in 1919, Socialism was already dead as a doctrine: it existed only as a hatred. There remained to it only one possibility of action, especially in Italy, reprisals against those who had desired the War and who must now be made to expiate its results. The Popolo dItalia was then given the sub-title of The newspaper of ex-service men and producers, and the word producers was already the expression of a mental attitude. Fascism was not the nursling of a doctrine worked out beforehand with detailed elaboration; it was born of the need for action and it was itself from the beginning practical rather than theoretical; it was not merely another political party but, even in the first two years, in opposition to all political parties as such, and itself a living movement. The name which I then gave to the organization fixed its character. And yet, if one were to re-read, in the now dusty columns of that date, the report of the meeting in which the Fasci Italiana di combattimento were constituted, one would there find no ordered expression of doctrine, but a series of aphorisms, anticipations, and aspirations which, when refined by time from the original ore, were destined after some years to develop into an ordered series of doctrinal concepts, forming the Fascist political doctrinedifferent from all others either of the past or the present day.

If the bourgeoisie, I said then, think that they will find lightning-conductors in us, they are the more deceived; we must start work at once.... We want to accustom the working-class to real and effectual leadership, and also to convince them that it is no easy thing to direct an industry or a commercial enterprise successfully.... We shall combat every retrograde idea, technical or spiritual.... When the succession to the seat of government is open, we must not be unwilling to fight for it. We must make haste; when the present rgime breaks down, we must be ready at once to take its place. It is we who have the right to the succession, because it was we who forced the country into the War, and led her to victory. The present method of political representation cannot suffice, we must have a representation direct from the individuals concerned. It may be objected against this programme that it is a return to the conception of the corporation, but that is no matter.... Therefore, I desire that this assembly shall accept the revindication of national trades-unionism from the economic point of view....

Now is it not a singular thing that even on this first day in the Piazza San Sepolcro that word corporation arose, which later, in the course of the Revolution, came to express one of the creations of social legislation at the very foundation of the rgime?

The years which preceded the march to Rome were years of great difficulty, during which the necessity for action did not permit of research or any complete elaboration of doctrine. The battle had to be fought in the towns and villages. There was much discussion, butwhat was more important and more sacredmen died. They knew how to die. Doctrine, beautifully defined and carefully elucidated, with headlines and paragraphs, might be lacking; but there was to take its place something more decisiveFaith. Even so, anyone who can recall the events of the time through the aid of books, articles, votes of congresses and speeches of great and minor importanceanyone who knows how to research and weigh evidencewill find that the fundamentals of doctrine were cast during the years of conflict. It was precisely in those years that Fascist thought armed itself, was refined, and began the great task of organization. The problem of the relation between the individual citizen and the State; the allied problems of authority and liberty; political and social problems as well as those specifically nationala solution was being sought for all these while at the same time the struggle against Liberalism, Democracy, Socialism and the Masonic bodies was being carried on, contemporaneously with the punitive expedition. But, since there was inevitably some lack of system, the adversaries of Fascism have disingenuously denied that it had any capacity to produce a doctrine of its own, though that doctrine was growing and taking shape under their very eyes, even though tumultuously; first, as happens to all ideas in their beginnings, in the aspect of a violent and dogmatic negation, and then in the aspect of positive construction which has found its realization in the laws and institutions of the rgime as enacted successively in the years 1926, 1927, and 1928.

Fascism is now a completely individual thing, not only as a rgime but as a doctrine. And this means that to-day Fascism, exercising its critical sense upon itself and upon others, has formed its own distinct and peculiar point of view, to which it can refer and upon which, therefore, it can act in the face of all problems, practical or intellectual, which confront the world.

And above all, Fascism, the more it considers and observes the future and the development of humanity quite apart from political considerations of the moment, believes neither in the possibility nor the utility of perpetual peace. It thus repudiates the doctrine of Pacifismborn of a renunciation of the struggle and an act of cowardice in the face of sacrifice. War alone brings up to its highest tension all human energy and puts the stamp of nobility upon the peoples who have the courage to meet it. All other trials are substitutes, which never really put men into the position where they have to make the great decisionthe alternative of life or death. Thus a doctrine which is founded upon this harmful postulate of peace is hostile to Fascism. And thus hostile to the spirit of Fascism, though accepted for what use they can be in dealing with particular political situations, are all the international leagues and societies which, as history will show, can be scattered to the winds when once strong national feeling is aroused by any motivesentimental, ideal, or practical. This anti-Pacifist spirit is carried by Fascism even into the life of the individual; the proud motto of the Squadrista, Me ne frego (I do not fear), written on the bandage of the wound, is an act of philosophy not only stoic, the summary of a doctrine not only politicalit is the education to combat, the acceptance of the risks which combat implies, and a new way of life for Italy. Thus the Fascist accepts life and loves it, knowing nothing of and despising suicide: he rather conceives of life as duty and struggle and conquest, life which should be high and full, lived for oneself, but above all for othersthose who are at hand and those who are far distant, contemporaries, and those who will come after.