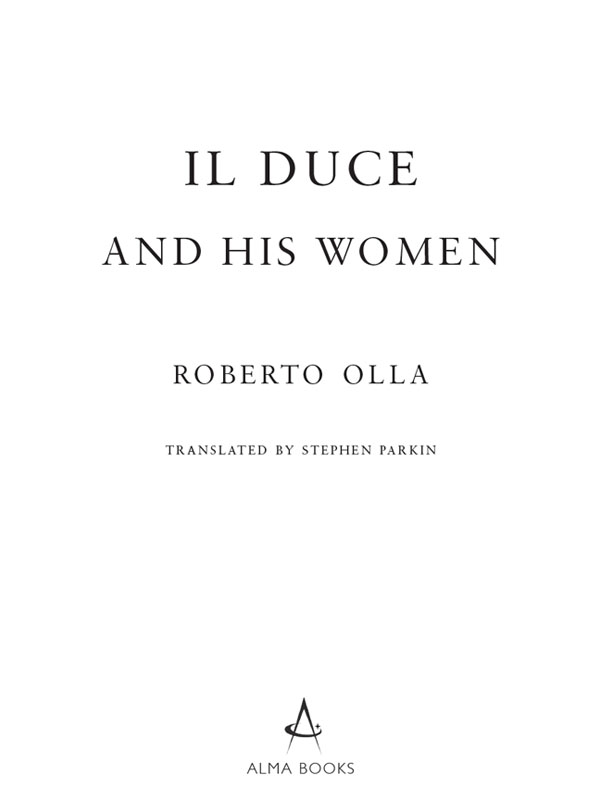

IL DUCE

AND HIS WOMEN

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almabooks.com

Il Duce and His Women first published by Alma Books Limited in 2011

Copyright Roberto Olla, 2011

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Mackays

ISBN (HARDBACK): 978-1-84688-135-0

ISBN (TRADE PAPERBACK): 978-1-84688-146-6

EPUB eISBN: 978-1-84688-202-9

MOBI eISBN: 978-1-84688-203-6

All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission, presumed to be in the public domain or reproduced under the terms of fair usage. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status of all the material cited, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

IL DUCE

AND HIS WOMEN

Introduction

Sex and politics, sex and power, sex and violence: this book is about sex, and readers should know this before they begin to turn its pages and learn about the private life of Benito Mussolini, the man who invented Fascism and became a model for other twentieth-century dictators. Obviously it is possible to write about sex in many different ways; normally it is best to treat the subject with tact, to find words which mediate the reality and an approach which doesnt weigh the narrative down. In the present case, however, where sources have been cited directly, thus giving a direct contact with the historical truth, tact and elegance have occasionally had to be sacrificed. The sex which is the subject of this book was at the centre of the myth of Mussolini: all the rest turned on this, like a wheel round a hub. His image as a man of power, the supreme man of power, drew directly on the idea of sexual potency as a symbol of eternal youth, physical and political. Many rumours about Mussolinis potency circulated among women whispered no doubt, accompanied by blushes during his twenty-year dictatorship, and in the same way anecdotes, tinged with envy, were bandied about among men. In the taverns and bars no doubt such tales, in frank and frequently off-putting detail, abounded. Such material has been deliberately ignored by academic historians. But this is the nub of the issue in this book, since it deals directly with such accounts. The recent publication of new documents relating to the Duces principal mistresses and lovers has made it possible to focus on the sexual dimension in all its reality which lay at the heart of the cult of Mussolini. And although efforts have been made to tone down some of the more vulgar and violent features found in these accounts, in citing the documents directly such aspects inevitably come to the fore. What kind of sex am I referring to? One example one quotation can illustrate this better than lengthy explanations. Mussolinis remarks to his last mistress, his favourite, Clarice Petacci, known as Claretta, show with uneuphemistic directness the way he displayed his sexual potency: You

What kind of source material has Clarice Petacci provided? She enjoyed keeping her diary, she enjoyed writing in it for the sake of writing, and rereading what she had written to while away the hours of waiting between a telephone call and the next meeting. She wrote quickly, putting down all that she recalled Mussolinis outbursts of anger, the sensations and emotions she felt, remarks he made: Im an animal, Im made like that, I resist and then I fall. Its like screwing a whore, as if Id gone with a whore.

So Clarice-Claretta was far from being a silly goose of a girl like some of the giddy-headed mistresses powerful men tend to seek out. She had had a decent education, had studied music and drawing, and came from a solid and prosperous middle-class background. Her father, Francesco Saverio Petacci, was a leading medical doctor who had held the highly prestigious position of Archiatra Pontificio, Pope Pius XIs personal physician. Despite the spelling mistakes and occasional omissions of a subject or verb, her style manages to be both restrained and vivid. Despite her efforts to record them faithfully, when she felt she couldnt reproduce the deliberately obscene and excessive aspects of Mussolinis talk, she tried to put matters as delicately as possible, as if the readability of the diary and the pleasure a reader including herself as a rereader might take in it mattered to her: His face is tense, his eyes are burning. I am sitting on the floor; quite suddenly he slides off his armchair onto me, curved over me. I can feel his body strain to unleash itself. I pull him

There is a story that one day in the 1920s Mussolini decided to drive his sports car himself, putting his usual chauffeur in the passenger seat, and had to stop at a level crossing to wait for a train to pass through. While waiting he opened the door, took off his driving goggles and got out to have a look round. Some women were also waiting to cross and watched him. He looks like the Duce, one of them said to general amusement. Mussolini saw them and immediately struck a familiar pose, with hands on hips, chin raised and chest pushed out. One of the young women who was bolder than the others stepped forward and said to him: Do you know you look a lot like the Duce? What would you say if I told you I am the Duce? replied Mussolini. The woman retorted: Come off it hes much better looking. This is the kind of story or anecdote which frequently crops up in the following pages, according to the situations described, just as they circulated among Italians who lived during the Fascist regime and were told to later generations. The stories are not in the book as part of an attempt to fictionalize the historical account; they represent an aspect or element of the myth of Mussolini the Duce which needs to be acknowledged and examined. He himself liked to be kept informed of the stories and rumours that circulated about him, even the anti-Fascist ones so long as they centred on him and his personality. They must have been common in the daily life of the Italians living under the regime: uncles or other relatives could feel safe in passing on to their families the latest anecdote theyd heard, or friends chatting in the coffee bar or taking a weekend stroll together could swap stories about their leaders private life. There was always someone whod heard something from someone else, someone whod actually set eyes on him, even if only from a distance: Mussolinis closely shaved Roman head, which fascinated women; Mussolinis jutting square jaw; Mussolini with his cat, on his horse, playing his violin, fondling his pet lion, driving his Torpedo, in swimming trunks, with his blazing eyes and powerful naked torso, with a look of gritty determination at the wheel of his racing car or an air of daring at the controls of his plane. Whoever had seen the Duce close up and lots of people had had a story to tell those who hadnt been so lucky. All these voices, all these people with their stories, created a huge wave of popular consensus, filling in, like some kind of putty, the cracks and gaps in the vast mosaic of the regimes propaganda, helping to lend three-dimensionality to the myth: Mussolini the sportsman, Mussolini the aviator, Mussolini the writer, the musician, the dancer, the warrior and even, if need be, Mussolini the peasant. Anti-Fascism too at a popular level thrived on stories and anecdotes, to be told in secret only to trusted friends, otherwise one risked ending up in forced internment or in prison. A booklet by a pseudonymous Calipso was published in Rome in the immediate wake of the citys liberation in 1944 with the title