This edition is published by Arcole Publishing www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books arcolepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1925 under the same title.

Arcole Publishing 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

MY DIARY 1915-1917

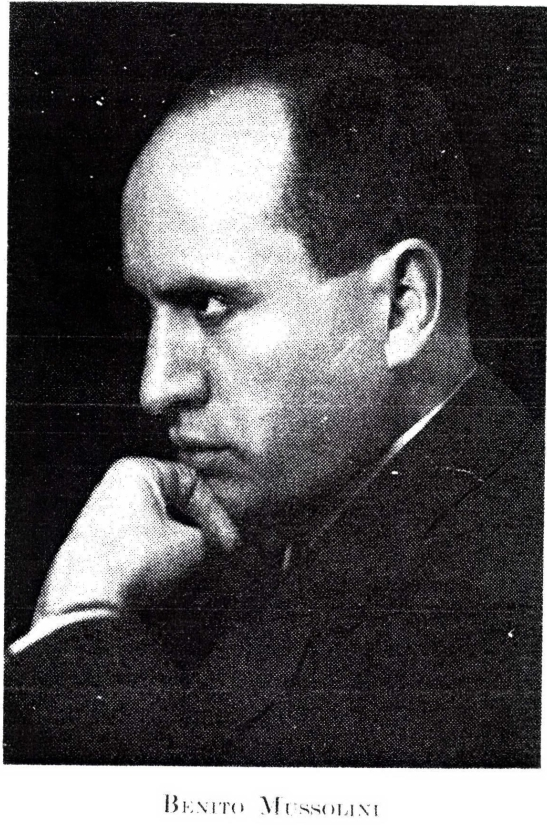

BENITO MUSSOLINI

Translated by

RITA WELLMAN

PREFACE

Fame for more than twenty-six centuries has gathered laurels for the Latin brow. At Varano dei Costa, close to the Tuscan boundaries and near the Adriatic, the same coast where Gabriel dAnnunzio, Francesco Paola Michetti, Giacomo Leopardi, Adolfo de Bosis and Giacomo Boni, and several others representative of the highest standards of modern Italian culture were born, the name Mussolini is added to the romantic history of Italys national life.

Mussolinis father, Alexander, a blacksmith, was not an unlearned man. He was an idealist and favored the principles of socialism. Mussolinis mother, an all-sacrificing soul, helped him to qualify himself for his first position, which was that of a school-teacher. From their provincial class he developed into a scholar. But it was only through early impractical experiments in the world of human contacts and problems that he finally evolved his political theories to become the inspiration of the new epoch in Europe.

Mussolinis whole life has been that of extreme discipline. Suffering through all stages of socialism and syndicalism, he learned the principle of cause and effect, proving himself great in the very fact that he could grow from one political conviction into another, and thus by evolution assisted by marvelous endowments, he emerged into the unique, honest dictator who has made the whole world look up in admiration.

When Mussolini was eighteen years old, after his first race in politics, he went to Switzerland. He had earned fifty-six lira per month by teaching forty little boys, but he had saved nothing. Therefore, his father provided funds for his journey.

In Switzerland Mussolini became a Mason. He worked as a laborer, taught French, always finding time to study. After two years, having come under the suspicions of the Swiss authorities, because of his radical ideas, he was expelled from the country. Going into Austria, he collaborated with Italian newspapers. About this period of his life, Mussolini discovered that by natural will and magnetism he could conquer anyone who came within the radius of his powerful personality.

Just before the Turkish war, having been expelled from Austria, he was sent as representative from his own town to the great Socialist Congress of Bolognia, where his genius was revealed by a speech so masterful that instantly he was recognized as the leader of the Socialists, and was appointed the editor of LAvanti. When the war was declared he began to see more clearly the direction for his energies. Mussolini, who was militant in Socialistic ranks, broke away from his companions when the Socialists of Italy decided to oppose and boycott the war. He declared himself to be first Italian and then Socialist, and he gave the example by enlisting. He went into the army as a corporal and thereby learned the actualities of mutual sacrifice with humanity. It was through this war experience that all of his previous ideas were replaced by the theories that formed the basis for the Fascist party.

In My Diary, written when he was the Bersagliere Mussolini, he recounts the vicissitudes of the trench life. In it, he says to his comrades of the trench: To you, I dedicate this journal of the war. It is mine and yours. My life and your life are in these pages; the monotonous, emotional, simple and exciting life we lived through together in the unforgettable days in the trenches.

Mussolini after being wounded was unable to go back to the front. He therefore returned to his sincere editorial writing, his trenchant public speaking, and founded Il Popolo dItalia which is now the leading Fascist journal and edited by his most capable brother.

Following the armistice, the Communists in Italy began to undermine the very foundations of industrial order. The American Consul-General at Naples told me that for three months no cars ran in that city. Disorders born of Russia put the entire nation out of economical action. At the same time the government in Rome, being weak and too much under the influence of demagogic politicians, was killing the national morale. Some of the stories of these machinations are positively mediaeval in conception and perpetration.

When I arrived in Rome, the spring of 1922, the streets were conspicuous with the unemployed. Appalling accounts of riots throughout Italy were every-day occurrences. The Banca di Sconto had failed and the people were hopeless. The traditional type of Military Police known as the Carabinieri were discouraged.

It was in Milan, the commercial center of Italy, that Mussolini founded his fasci. Organized after the ancient Roman army, its legions soon spread throughout Italy. Within two years, Il Duce, the leader, had every department of the black-shirts under control, its units, representing the splendid youth of the entire Nation, including a Womans Corps.

The march against the feeble government at Rome and other destructive elements in Italy, established a new precedent in the history of National Military Movements. It was a spiritual crusade, and the direct antithesis of the revolution of the materialists in Russia. Italy had saved European civilization twiceyoung Italy was saving European civilization again, and without bloodshed.

Mussolinis ideals of government admit that a man is free to just the extent that his actions contribute towards the good for all, or the betterment of the State.