Pagebreaks of the print version

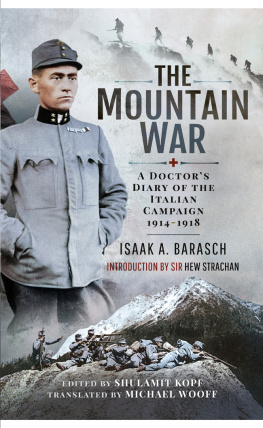

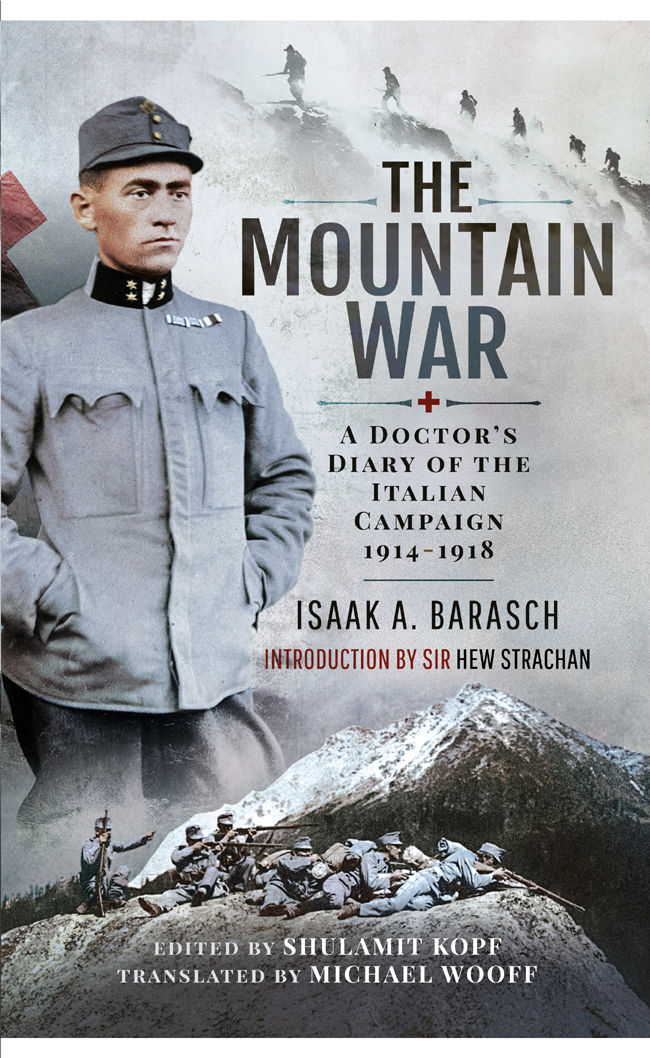

The Mountain War

The Mountain War

A Doctors Diary of the Italian Campaign 19141918

Isaak A. Barasch

Edited by

Shulamit Kopf

Translated by

Michael Wooff

Introduction by

Sir Hew Strachan

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright English text of diary Shulamit Kopf 2021

Copyright Introduction and chapter introductions Hew Strachan 2021

ISBN 978 1 39909 310 1

eISBN 978 1 39909 311 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39909 311 8

The right of Isaak A. Barasch to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Preface

by Shulamit Kopf

S o many historical documents crumble to dust, vanish, get tossed or lost by people not cognisant of their value. Thousands languish in attics, shoeboxes, drawers, buried underground or forgotten in archives. That could have easily been the fate of the six diaries handwritten during the First World War by my great-uncle, Dr Isaak A. Barasch, who served in the Austro-Hungarian army on the Italian front. He didnt survive the war having succumbed to the Spanish flu epidemic on 12 September 1918. Had the diaries remained with our family in Poland, the diaries would have vanished in the next world war. It was lucky that his sister, Helen Mehlman, took them with her when she immigrated in 1922 with her family to New York City. There, in her antique-filled apartment on Riverside Drive, they stayed in a drawer for almost 100 years.

There are several people who have helped me rescue Dr Baraschs words from oblivion.

I want to thank Helens daughter, the late Irene Fingerhut, for entrusting the diaries to my care.

My son, Jonathan Waldmann, got the project going by finding an excellent and dedicated German-to-English translator, which brings me to my big heartfelt thanks to Michael Wooff who took the project as a job until it became a mission. He fell under the spell of Dr Baraschs prose. Your great-uncle is such good company. He seems to have a knack for befriending people and of appreciating the finer things of life Good for him, he wrote. Your great-uncle deserves to be bequeathed to posterity.

British military historian, Hew Strachan, professor at the University of St Andrews, is accustomed to receiving letters from people in possession of historical documents relevant to the First World War that they would like him to examine. He was kind enough to read Dr Baraschs diaries and immediately recognised their importance. He has my heartfelt gratitude for deciding to take on their publication as a project. I couldnt have accomplished this mission without him. It is thanks to him that this book exists.

My gratitude also goes to Erwin Schmidl, a military historian in Vienna, who was kind enough to send me his book Jews in the Habsburg Armed Forces , and to patiently answer my numerous questions. We were both shocked when I discovered a family connection to General Alexander Ritter von Eiss, one of the generals he mentions in his book.

Sonja Lessacher at the University of Vienna Medical School archives sent me Dr Baraschs academic records.

Thank you to my son, David Beyer, and Dana Beyer who made some excellent editorial suggestions for the chapter I wrote.

A big thanks to Rupert Harding at Pen & Sword for accepting the diaries for publication with such great enthusiasm.

And you, dear reader, if you stumble across yellowing letters, journals or old documents when you clean out the homes of your grandparents, dont throw them out.

List of Plates

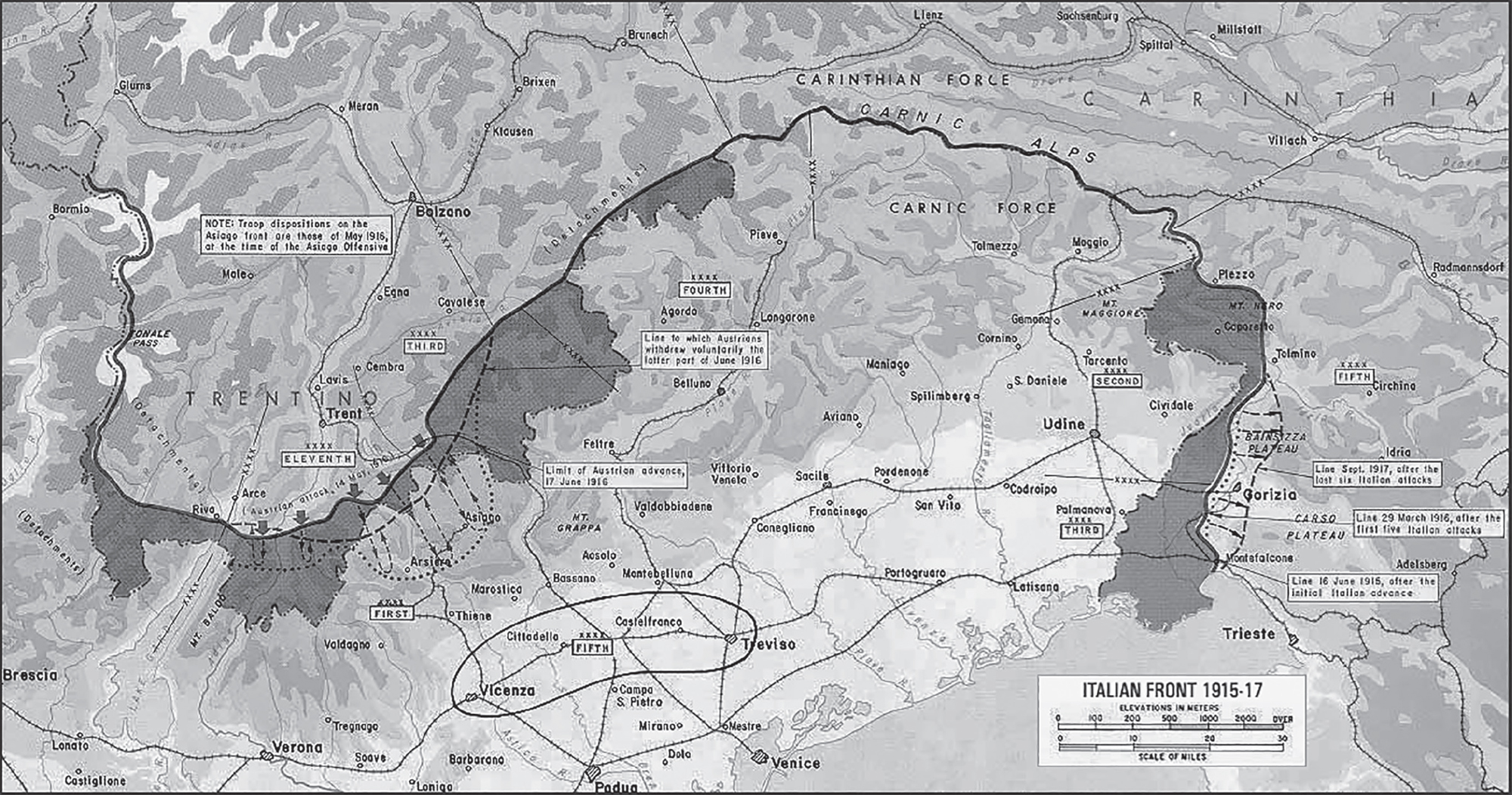

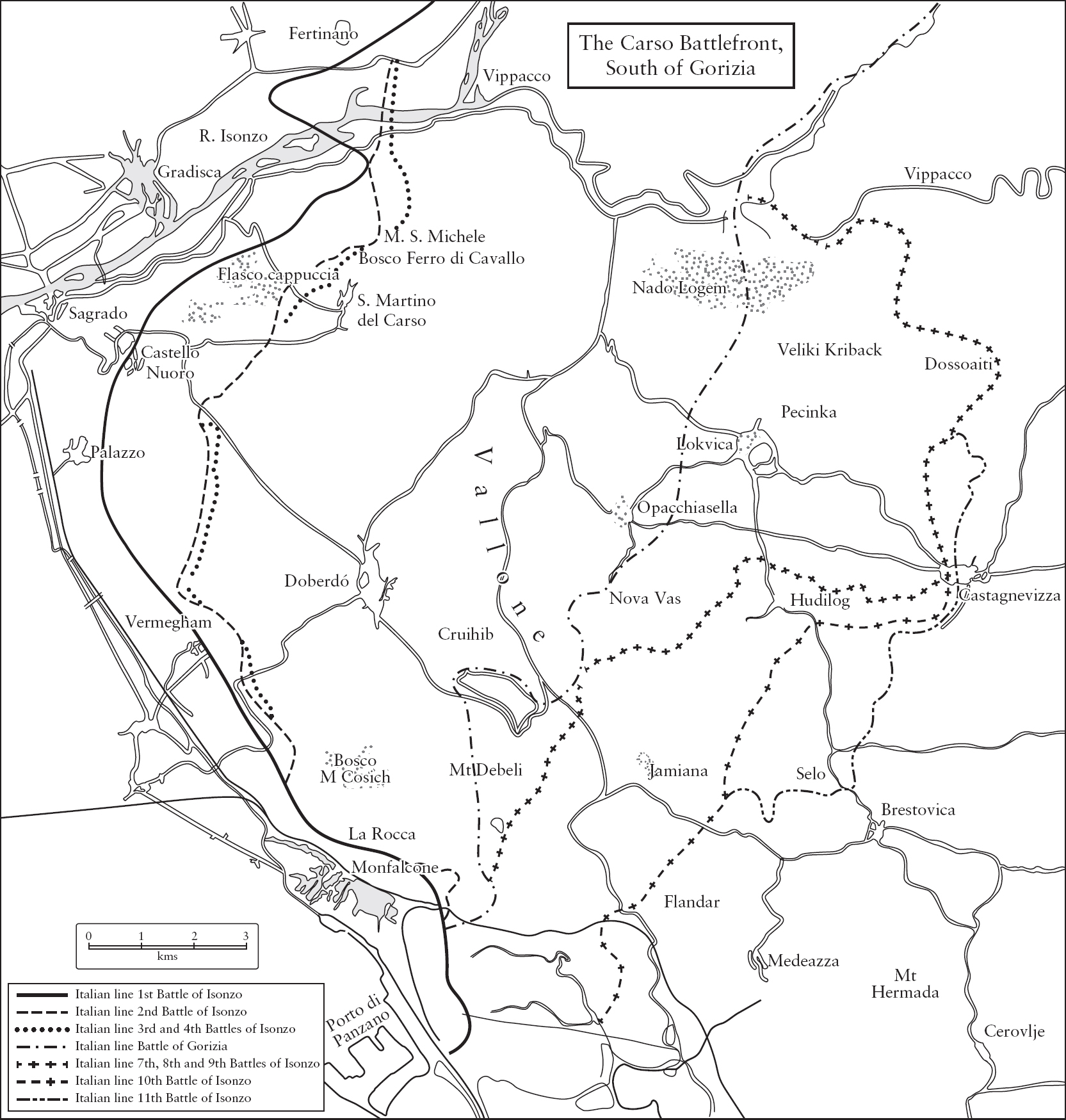

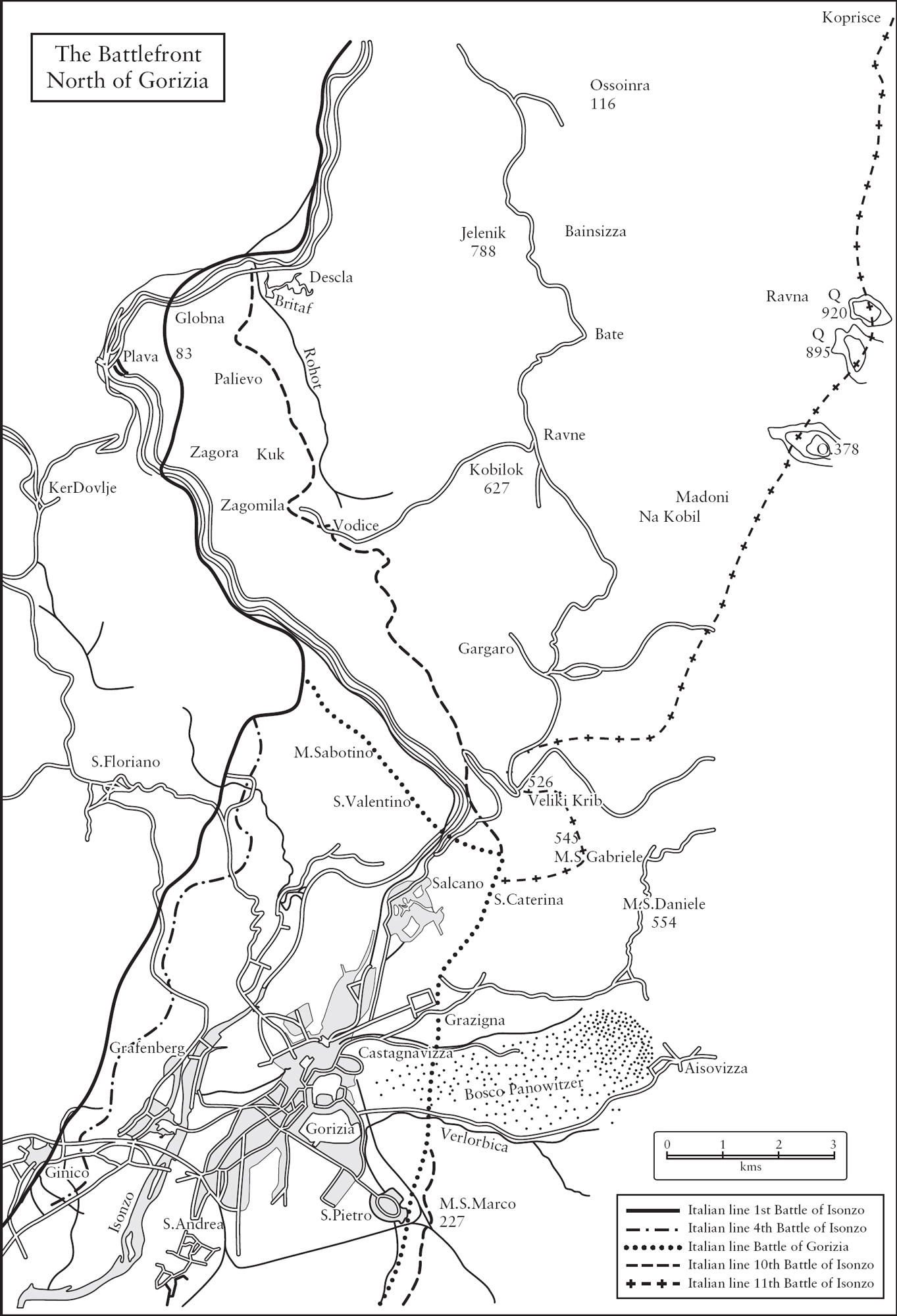

Maps

Introduction

by Hew Strachan

Austria-Hungary and the Outbreak of the First World War

O n 28 June 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand was killed in Sarajevo in what was then Bosnia-Herzegovina. The conspiracy theories which followed his death and the counter-factual accounts of what would have happened if he had lived testify to the confused status of the Habsburg empire at the beginning of the twentieth century. Some saw the heir apparent as the victim of an internal plot, deliberately exposed to a terrorists bullet by the decision that he should visit the newly annexed province without adequate security. Others speculated as to the course he would have followed if he had succeeded his aged uncle, Franz Josef, as emperor.

According to one side he would have saved the empire by recentralising control. In 1867, after Austrias defeat at the hands of Prussia, the empire had been reconstructed as a dual monarchy, one part Austrian with its capital in Vienna and the other Hungarian and based in Budapest. An alternative view countered that he planned to take the compromise of 1867 further, creating a separate South Slav entity (which would have included Bosnia-Herzegovina). In Viennese eyes, a tripartite solution to the governance of the Habsburg lands would have put the bumptious and often fractious Magyars from Budapest in their place, so allowing Austrian common sense to divide and rule. The Magyars were outnumbered by Slavs even within Hungary; they would be definitively weakened if the Slavs formed an independent political identity.

While alive, Franz Ferdinand had toyed with both options, initially favouring federalism or a three-way split and then veering towards renewed centralisation. Both were means, indirect or direct, for asserting his authority, and both confirmed that the current structure was confronting imminent and dramatic change. Franz Josef had ascended the throne at the age of 18 on the abdication of his uncle in 1848. Few could remember a time when he had not been emperor, but he was now 84 and his subjects had to ready themselves for the end of an era. Many did so with trepidation. Franz Ferdinand himself was not a particularly attractive personality or a natural reformer. He seemed to be more radical than he was thanks to his decision to marry a comparatively humble Czech countess in a genuine love match. He had also countered the more bellicose instincts of the chief of the armys general staff, Franz Conrad von Htzendorf, and would probably have blocked the rush to war which followed his assassination. But he was also a bully with a short fuse, an anti-Semite, and as convinced of his royal and imperial authority as any of his predecessors.