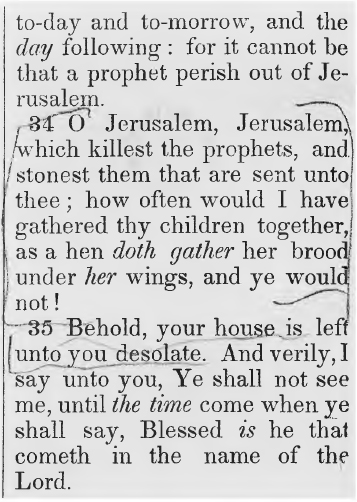

Herman Melvilles penciled marginal annotations in his copy of The Authorized New Testament with Psalms (New York: American Bible Society, 1844). The passages are from Luke 13. (By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.)

In the centre of Georgianas left cheek, there was a singular mark, deeply interwoven, as it were, with the texture and substance of her face. In the usual state of her complexion,a healthy, though delicate bloom,the mark wore a tint of deeper crimson, which imperfectly defined its shape amid the surrounding rosiness. When she blushed, it gradually became more indistinct, and finally vanished amid the triumphant rush of blood, that bathed the whole cheek with its brilliant glow. But, if any shifting emotion caused her to turn pale, there was the mark again, a crimson stain upon the snow, in what Aylmer sometimes deemed an almost fearful distinctness. Its shape bore not a little similarity to the human hand, though of the smallest pigmy size.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Birth-mark

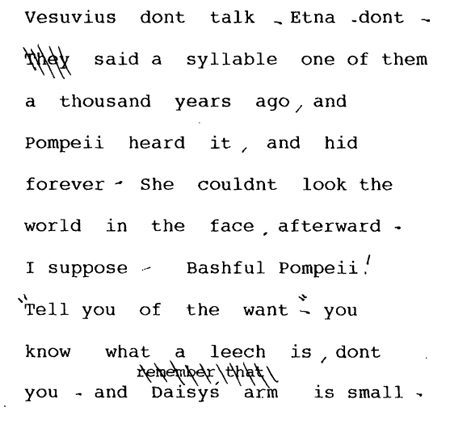

Emily Dickinson, Third Master Letter

Though our Handsome Sailor had as much of masculine beauty as one can expect anywhere to see; nevertheless, like the beautiful woman in one of Hawthornes minor tales, there was just one thing amiss in him. No visible blemish indeed, as with the lady; no, but an occasional liability to a vocal defect. Though in the hour of elemental uproar or peril he was everything that a sailor should be, yet under sudden provocation of strong heart-feeling his voice, otherwise singularly musical, as if expressive of the harmony within, was apt to develop an organic hesitancy, in fact more or less of a stutter or even worse.

Herman Melville, Billy-Budd

Acknowledgments

Patricia Caldwells The Puritan Conversion Narrative: The Beginnings of American Expression and Charles Lloyd Cohens Gods Caress: The Psychology of Puritan Religious Experience examine, in different ways, a body of materials not featured in our American literary canon. The texts they examine are testimonies, delivered by men and women, in the gathered Nonconformist churches of England, Ireland, and New England between the 1630s and the Restoration. Few of these religious narratives have survived. On the American side, the most interesting collection is a group of fifty-one recorded in a small private notebook by Thomas Shepard, the minister of the First Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, between 1637 and 1645, either as they were being delivered or shortly afterward from notes and memory. The first complete edition of these narratives, edited by George Selement and Bruce C. Woolley, was published in volume 58 of Collections of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in 1981. Some of these confessions of faith had previously appeared in other anthologies, but none of those given by women. Apart from the court records of Anne Hutchinsons trials and a few brief relations in John Fiskes and Michael Wigglesworths notebooks, these testimonies represent the first voices of English women speaking in New England. As in Anne Hutchinsons case their words were transcribed by male mediators who were also community leaders. The Puritan Conversion Narrative demonstrates how careful examination and interpretation of individual physical artifacts from a time and place can change our basic assumptions about the New England pattern and its influence on American literary expression.

Caldwells study is concerned with how and when English voices began speaking New-Englandly. In her essay The Antinomian Language Controversy (Harvard Theological Review 69 [1976] pp. 34567), Caldwell writes: trial documents suggest that Mrs. Hutchinson was neither purposely deceiving nor hallucinating, and that her words cannot fairly be ascribed to mere stubbornness, hysteria, and personal assertiveness, nor even to a poor education. They suggest that Mrs. Hutchinson was speaking what amounts to a different languagedifferent from that of her adversaries, different even from that of John Cottonand that other people may have been speaking and hearing as she was, and that what happened to them all had serious literary consequences in America (pp. 34647). This antinomian language occurred again in the controversial years before, during, and immediately after the American Civil War. Michael Colacurcio and Amy Shrager Lang have shown that Hawthornes short stories and The Scarlet Letter are inspired and unsettled by Mrs. Hutchinsons role as a prophetic religious leader.

Amy Shrager Langs Prophetic Woman: Anne Hutchinson and the Problem of Dissent in the Literature of New England demonstrates that American antinomianism is a separate phenomenon from its European counterpart. Here, the history of antinomianism in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (163537), encoded in the story of Anne Hutchinson, is gendered from the beginning. Langs thesis that the local history of antinomianism is distinct from its universal one was supplanted for me by Anne Kibbeys invaluable chapter, 1637: The Pequot War and the Antinomian Controversy, in The Interpretation of Material Shapes in Puritanism, a book to which I return again and again, and by Stephen Greenblatts The Word of God in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in his Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare. This essay has been important to my thinking about sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English Protestant biblical translators, prophets, and heretics.

My work on Mary Rowlandson was originally inspired and explicitly aided by Richard Slotkins Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 16001860. Julia Kristevas Semiotics of Biblical Abomination, in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, was helpful for a reading of Rowlandsons narrative. Cotton Mather and Benjamin Franklin: The Price of Representative Personality, by Mitchell Robert Breitwieser, and Kenneth Silvermans The Life and Times of Cotton Mather contributed to my understanding of Cotton Mather. Gods Plot: The Paradoxes of Puritan Piety, Being the Autobiography & Journal of Thomas Shepard, edited and with an illuminating introduction by Michael McGiffert, brings Shepard alive as no other writing about him has done. The Selement and Woolley edition of Shepards Confessions have been indispensable, not least for the genealogical records they so painstakingly supplied for each speaker. I have, in Incloser, retained the names Shepard used as headings for his narratives; the section on beaver dams in this essay draws on William Cronons Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, a book I also found useful in more general ways in my Rowlandson essay. Although my reading of American literary expression is bleaker than readings offered by Sacvan Bercovitch, I have profited from his reassessments of the Puritan errand.

When I started Incloser, I used Websters Third New International Dictionary as the source for a definition of enclosure. Since then I have come to believe that what is crucial when trying to understand what makes the literary expression of Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Dickinson, and to a lesser extent Hawthorne singularly North American is their useand in Dickinsons case, intentional misuseof Noah Websters original