S.S. Prawer - Nosferatu (1979)

Here you can read online S.S. Prawer - Nosferatu (1979) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Nosferatu (1979)

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nosferatu (1979): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nosferatu (1979)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nosferatu (1979) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nosferatu (1979)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

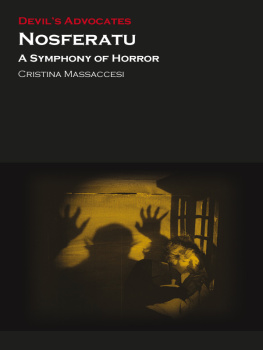

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics is a series of books that introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles available in the series, please visit our website: www.palgrave.com/bfi

Magnificently concentrated examples of flowing freeform critical poetry.

Uncut

A formidable body of work collectively generating some fascinating insights into the evolution of cinema.

Times Higher Education Supplement

The series is a landmark in film criticism.

Quarterly Review of Film and Video

Possibly the most bountiful book series in the history of film criticism.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, Film Comment

Editorial Advisory Board

Geoff Andrew, British Film Institute

Edward Buscombe

William Germano, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Lalitha Gopalan, University of Texas at Austin

Lee Grieveson, University College London

Nick James, Editor, Sight & Sound

Laura Mulvey, Birkbeck College, University of London

Alastair Phillips, University of Warwick

Dana Polan, New York University

B. Ruby Rich, University of California, Santa Cruz

Amy Villarejo, Cornell University

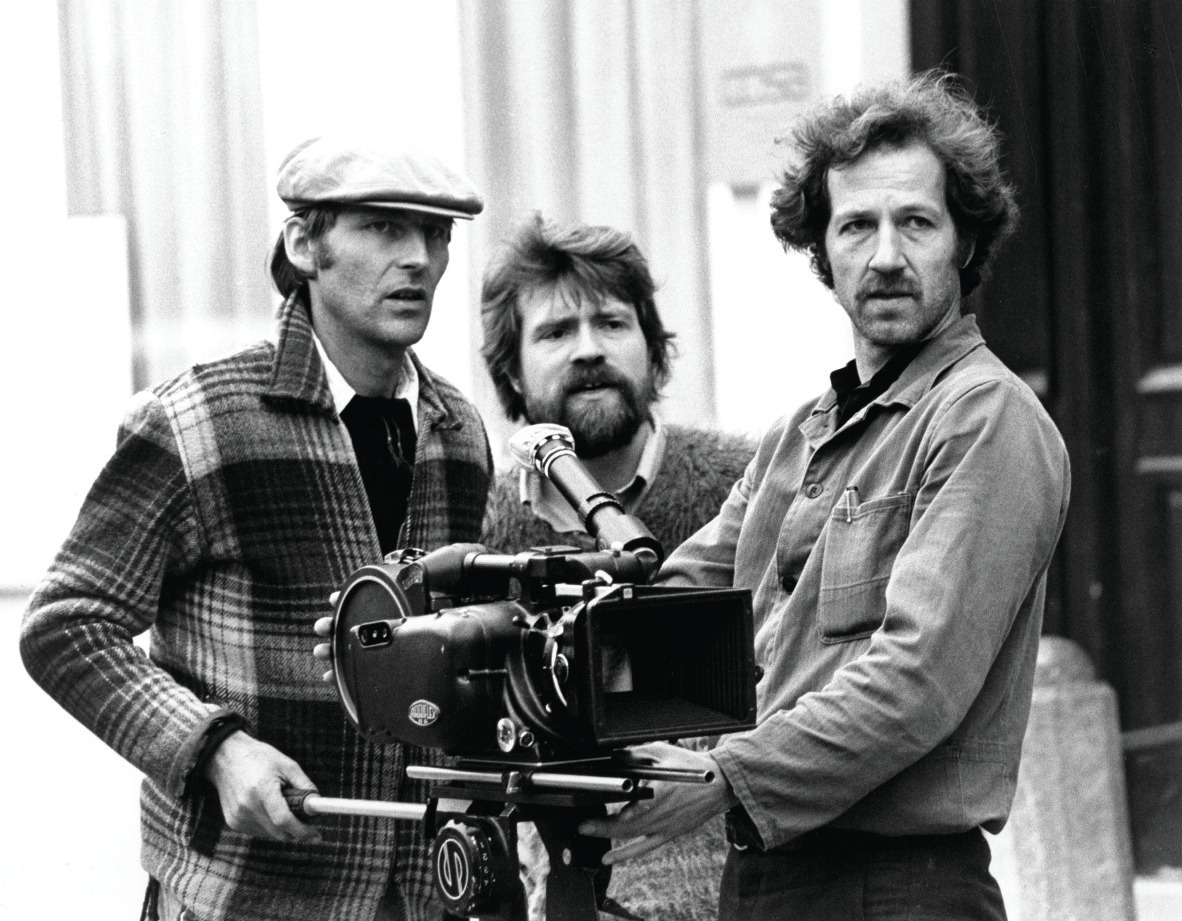

Filming Nosferatu: (left to right) Jorg Schmidt-Reitwein (Director of Photography), Henning von Gierke (Art Director), Werner Herzog

For Sir Alan and Lady Budd in friendship and gratitude

Contents

Werner Herzogs Nosferatu Phantom der Nacht (1979) weaves a self-conscious web of its many aesthetic influences. Drawing on an exceptionally broad body of knowledge, Siegbert Salomon Prawer connects Herzogs sounds and images to their antecedents, one after the next. Prawers wide-ranging associations include nods to Ann Radcliffes Gothic novels as well as to the Swiss painter Henry Fuselis ghostly work The Nightmare (1781). The stony, weathered, uninhabitable edifice behind which Herzogs vampire appears to reside calls Radcliffes vivid depictions of crumbling castles to mind. Both her writing and Fuselis painting have each come to be associated with the Gothic style, which, owing to its indirect association with Gothic architectural modes in contradistinction to Greco-Roman examples was originally considered to be Germanic. Although the imagery indeed resonates with Radcliffe, and one of the films major sources was Bram Stokers Victorian Gothic novel Dracula (1897), Herzogs most overwhelming influence was the German director F. W. Murnau, whose film he was reworking. Murnau had studied art history and philology, all of which worked their way into his films, including his highly synthetic 1926 adaptation of Faust, his Phantom (1922), based on Gerhart Hauptmanns eerie Germanic story, and his own Nosferatu (19212), in which, for example, a Gothic turret in the opening shot plainly echoes one of Ludwig Kirchners Expressionist paintings.

Prawer is right to return to the sources: like Murnau, Herzogs cinematic style is strongly influenced by contact with other arts, starting with his first feature film, Signs of Life (1968), in which landscapes lined with windmills deliberately evoke etchings by the Dutch artist Hercules Seghers. Over four decades later, Herzog was still preoccupied with similar fascinations, speculating into the origins of human pictorial production in Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010). The numerous artistically impacted compositions in Nosferatu can, in this sense, hardly be seen as a detour.

In an inspired and remarkably associative interpretation of Nosferatus artistic inheritance, Kenneth S. Calhoon notes resemblances between Herzogs imagery and works by Dutch artists including Pieter Claesz.has been vacated, and time, at least in the form of the films ever-progressing frames, continues on.

The Nietzschean desire to affirm mortality to own the brutal truth of death, embrace ones finitude and rejoice in it suggests that Herzogs worldview is informed by a belief in an infinitely remote God, a phrase Prawer uses more than once in the present study. The fact that Herzogs shot is staged similarly to da Vincis famous painting in that the diners sit at a long rectangular table, facing outward, toward the observer, indicates a knowingness where its theological provenance is concerned. Herzog struggles with Gods infinite remove, or the effective absence of divine will, throughout his films, particularly those from this period, such as his documentary La Soufrire (1977), which dealt with an active volcano on Guadeloupe and the small number of men who either because of choice or circumstance lingered at its base, anticipating disaster. Herzog made that film less than two years before Nosferatu, and its scrutiny of the lassitude with which people confronted their imminent deaths runs along similar lines to these images of Wismar at Nosferatus denouement.

The idea of resigning ones self to the here and now, and directly confronting the actuality of mortality, calls to mind the attention Prawer elsewhere paid to Martin Heideggers concept of Geworfenheit, or thrownness. For Heidegger at least for the Heidegger who wrote Being and Time our thrownness was little

In this regard the vampire in Nosferatu can be perceived as delivering not a plague, but rather a message to the people of Wismar. The plague can be seen as a gift. He suffers the pain of immortality so that humans may appreciate their finitude. In an exchange with Lucy, Herzogs Nosferatu explains that time is to him an abyss as deep as a thousand nights. She responds with her certain knowledge that the rivers will run on long after our deaths. She comprehends, in other words, mortality, and for this reason, she explains, she is capable of fully embracing her love for Jonathan; it is a mortal love born from finitude and thus in her words something she is not even willing to share with God. Lucy is thus not only Nosferatus redeemer, who ultimately, at the films end, releases him from his unending prison of a life, but she also understands the possibilities associated with living and loving in a world in which God remains wholly inaccessible; she is Nosferatus existential counterpart. The axis around which the film turns is not, then, the difference between Jonathan and Nosferatu; those two are kindred insofar as Jonathan can be understood to have sought out the vampire and, in the end, he is the one who extends the bloodthirsty legacy. The heart of the film is rather the difference between Nosferatu and Lucy, who are two sides of the same conceptual coin.

The themes of mortality and finitude appear universal, but Herzogs film was set in one specific age and produced in still another. Prawers interpretation draws on both of these histories, noting that Herzog made the decision to retain the middle-class and mid-nineteenth-century atmosphere from Murnaus film, the Biedermeier milieu associated with the period between the Napoleonic Wars and the revolution of 1848. Scenes of Jonathan and Lucy at the films beginning even imitate the Biedermeier style in the visual arts, and they evoke paintings by the Austrian artist Ferdinand Georg Waldmller. Herzogs visual style here corresponds to his content. In this case Herzog, drawing on Murnau, relies on Biedermeier motifs to suggest the narrowness of the couples domestic world. From this perspective,

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nosferatu (1979)»

Look at similar books to Nosferatu (1979). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nosferatu (1979) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.