Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

FINDING

PLACES

The Search for the Brains GPS

FINDING

PLACES

The Search for the Brains GPS

Unni Eikeseth

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

Translated by Lucy Moffatt

Published by

World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

5 Toh Tuck Link, Singapore 596224

USA office: 27 Warren Street, Suite 401-402, Hackensack, NJ 07601

UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA,

Norwegian Literature Abroad

Unni Eikeseth: Jakten p stedsansen. Hvordan May-Britt og Edvard Moser lste en av vitenskapens store gter

Copyright Vigmostad & Bjrke, Norway 2018

Sold through Winje Agency A/S, Skiensgate 12, 3912 Porsgrunn, Norway

FINDING PLACES

The Search for the Brains GPS

Copyright 2020 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the publishers.

ISBN 978-981-121-691-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-981-121-692-3 (ebook for institutions)

ISBN 978-981-121-693-0 (ebook for individuals)

For any available supplementary material, please visit

https://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/11735#t=suppl

Typeset by Stallion Press

Email:

Printed in Singapore

Contents

CHAPTER 1

An Unerring Instinct

W hite, white, white. The eyes of the Russian lieutenant Ferdinand von Wrangel and his men stung and ached in the sharp light reflected off the snow-covered sea ice. It was early April 1821. Just over a week earlier, the expedition had left the mainland and set off north across the frozen sea in 21 sledges drawn by a total of 240 dogs. For the first few days, they could still see the Baronov cliffs of the mainland on the horizon behind them. After that, the world around them became one endless icy plain, relieved only by open channels and pack ice.

Von Wrangel was leading one of the two Siberian expeditions dispatched by Czar Alexander. His mission was to map the coast of Siberia in exhaustive detail. The party was also supposed to investigate whether there was any uncharted territory in the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia, as other explorers claimed.

For von Wrangel and his men, being able to identify where they were and find their way back across the frozen sea, without landmarks by which to navigate, was a matter of life and death.

When open channels and large blocks of ice forced the expedition to switch direction, the lieutenant would set a course. Von Wrangel was aided by the most modern navigational instruments then available, including two chronometers, which served as portable time standards. In addition, he had a stopwatch, a sextant and an artificial horizon, three azimuth compasses, two telescopes, and a measuring line. Toward the end of each days leg, he would collate all the readings to determine the expeditions precise position. Remarkably, several of the experienced local sledge-drivers were far better than he was at calculating their position after a days travel across the ice, even without recourse to any navigational instruments. They appeared to be guided by a kind of unerring instinct, the lieutenant wrote in his account.

Von Wrangel was particularly impressed by a seasoned sledge-driver and guide, Sotnik Tatarinow:

In the midst of the intricate labyrinths of ice, turning sometimes to the right and sometimes to the left, now winding round a large hummock, now crossing over a smaller one, among such incessant changes of direction, he seemed to have a plan of them all in his memory and to make them compensate each other, so that we never lost our main direction, and whilst I was watching the different turns, compass in hand, trying to resume the route, he had always a perfect knowledge of it empirically. His estimation of the distances we had passed over reduced to a straight line, generally agreed with my determinations deduced from observed latitudes and the days course.

After nearly getting trapped in rotten, melting sea ice, von Wrangels expedition made its way back to the mainland by the skin of its teeth. They hadnt found any land to the north, but they had discovered several islands and filled in a few blanks on the map along the Siberian coast. Several decades after von Wrangels arduous journey, his account was published in English and read by the renowned evolutionary biologist, Charles Darwin. Darwin noted the description of the sledge-drivers incredible sense of direction and began to brood over how this could be possible.

In his twenties, Darwin had himself been on a long expedition aboard The Beagle. He was well aware how challenging it was to keep track of ones journey in the conditions that von Wrangel and his men had navigated. If you were constantly obliged to change course, neither a compass nor the Northern Star would be sufficient for determining your position on the open sea. The sledge-drivers must have been tapping into some subconscious ability to calculate speed, distance, and time. Yet, Darwin did not believe that the sledge-drivers had a special faculty. He suspected that all humans had an overview of where they were; the sledge-drivers simply appeared to have perfected this ability. Darwin figured this sense was influenced by sight, and perhaps information from ones own muscle movements.

And so Darwin formulated an idea that remained unproven long after his death. Could it be that some part of the brain was specialized for determining direction?

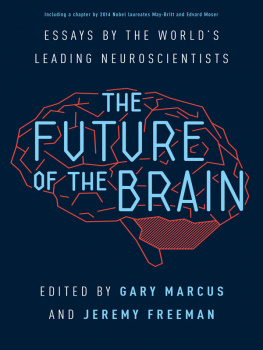

It would be another 130 years until this question was answered by a husband-and-wife research team at a small university in Norway.

CHAPTER 2

Hareid Planet Club

O ne afternoon in fall 1982, a chance meeting took place on an Oslo street. Thirty-two years later, two of the people who met would dominate the news for weeks on end when they received Norways first ever Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Nineteen-year-old May-Britt Andreassen had just finished her shift at the Kaffistova caf and was on her way down toward Karl Johans gate when she spotted a couple of familiar faces from her hometown. The people in question were yvind Strand, who had attended the same high school as her in Ulsteinvik, and Edvard Moser, from her chemistry class. Edvard told her he would be studying science in Oslo in the spring. May-Britt, who had been studying in the city for half a year, immediately offered to show Edvard around. She remembered what it was like when she was a newly fledged student, how strange and new everything was, and was keen to help him get to know the university and the city.