INSIDE THE CLOSED WORLD OF THE BRAIN

HOW BRAIN CELLS CONNECT, SHARE AND DISENGAGEAND WHY THIS HOLDS THE KEY TO ALZHEIMERS DISEASE

MARGARET T. REECE PHD

REECE BIOMEDICAL CONSULTING LLC

MANLIUS, NEW YORK

Text Copyright 2015 by Margaret T. Reece

Images licensed from . Images in the public domain in the United States are indicated in the figure legends. The remaining figures are licensed under various creative commons licenses at WikiMedia.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, at Attention: Permissions Coordinator, at the address below.

Margaret T. Reece PhD/Reece Biochemical Consulting LLC

8195 Cazenovia Road

Manlius, New York 13104

www.medicalsciencenavigator.com

Book Layout 2013 BookDesignTemplates.com; Cover Image Viktoriya, Shutterstock.com

Ordering Information:

Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, and others. For details, contact the Special Sales Department at the address above.

Inside the Closed World of the Brain/ Margaret T. Reece PhD 1st ed.

ISBN 978-0-9963513-1-7 (ebook)

For all who are dedicated to eradication of the long goodbye that is Alzheimers disease.

Preface

MOST EVERYONE HAS HEARD of Alzheimers disease, but few know much about it. Because I teach human physiology, friends, acquaintances, students, family members and strangers frequently ask me questions about it. What is Alzheimers disease? How is Alzheimers disease different than just getting old? Can I avoid Alzheimers disease by keeping my cholesterol level under control? Coming up with a clear accurate answer to these and similar questions over coffee or lunch is a challenge. First, words that describe how a brain routinely works require explanation. Second, some myths about the human brain must be dispelled. Third, the phases of Alzheimers disease prior to the appearance of symptoms need to be described. My goal with this book is to provide readers with state-of-the-art knowledge of how brain cells normally work together and where they may go astray to establish Alzheimers disease. There is considerable reason to believe that ongoing research efforts will produce ways to prevent, or sufficiently slow, Alzheimers disease so that people in the future can live a normal lifespan without experiencing this form of dementia.

Margaret T. Reece, PhD

Introduction

THE TEMPTATION TO READ are organized to progressively build a basic vocabulary for newcomers to the science. Medical students will find numerous facts on every page that are extracted from actual Step 1 exam questions.

, the consensus within psychology and neuroscience is presented concerning critical elements of memory formation and language acquisition.

Glossary and Further Reading sections are included at the end. Further Reading is a partial list of the original papers consulted in creating this book.

CONTENTS

Some things need to be believed to be seen.

STEVE JOBS

[ 1]

Tips & Tricks for Learning Scientific Language

THE STRANGE WORDS USED in anatomy and physiology make it difficult to follow discussions of the science. Because scientific language is an obstacle for many, this book begins by describing the secret to understanding the words needed to learn about what happens inside the human brain.

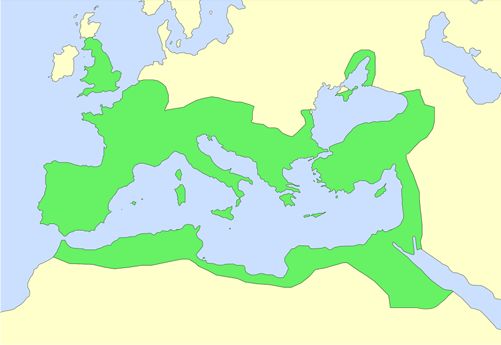

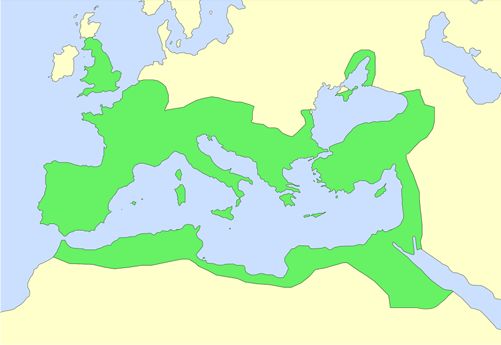

Human anatomic names were assigned when scholars wrote and lectured in Classical Latin. Classical Latin was the universal language of large segments of the western scientific world from the time of the Roman Em pire () through the 17th century. The good news is Latin can be translated into modern languages. Psychology research discovered words are learned fast by the human brain when they are associated with something familiar. Thus, assigning meaning to the Latin names makes them far easier to remember.

Figure: 1-1: Range of Latin language use in 60 AD shown in green. Illustration: Hannes Karnoefel

LANGUAGE AND SOUND

Infants and young children acquire their primary language through their brains instinctive interpretation of auditory input. By just hearing the subset of sounds used in the language spoken near them they can sort the sounds into their proper order and map them to importance. Most brain structures dedicated to processing of auditory signals are superb at discerning pitch of the human voice and assigning implication to tones and inflection.

Infants can distinguish all of the sounds of all of the worlds languages until about age six months. Between six months and a year, brain pathways devoted to language begin to form in support of the sounds most often heard. Learning to recognize and speak a language is instinctive for infants.

Adults trying to learn a second language find reading and writing a new language is not enough to develop fluency. Listening to language spoken in the correct manner over an extended period of time is needed. Auditory input is required to build new language pathways in the brain to parallel those of the native language learned in infancy.

Likewise, just reading scientific terminology does little to establish it in memory. Few people speak Classical Latin anymore, so a substitute auditory strategy is needed to help the mind map the sounds of scientific names to their meaning.

SCIENTIFIC VOCABULARY

Today much of the worlds population is at least familiar with the English language. Some argue English should be the primary language used to teach science. And, English in its various forms is, for the most part, derived from Latin. Latin and Greek scientific words present a greater challenge for those whose native language is not derived from Latin.

Translation of compound scientific words is not always direct. The simple descriptive nature is often hidden because of the patched together arrangement of many ideas. The solution is to break the long words into parts and to assign meaning to each part. Then the parts must be rearranged into a sensible order, and word order is not always the same from language to language. For example, in Latin adjectives follow nouns unlike English where adjectives precede nouns.

Because people become so uncomfortable with the sound of scientific words, they also fail to speak and write them with precision. Scientific terminology is often composed of made-up words, which seem almost like brief descriptive pseudo-sentences. If the compound words are not spoken with precision, the various parts may become mixed in a haphazard sequence producing nonsense descriptions. To keep the parts of compound scientific names in proper order, speaking and listening must be included in the learning process.

STRATEGIES AND TACTICS

Recent studies at colleges experimented with approaches to help students learn scientific and medical terminology. Design of the education experiments relied upon conclusions of investigators who study the brains process for learning language. Educators found reading a new and difficult word out loud three to five times each day for several days improved students ability to remember the word, to spell it and to better absorb printed material using the word. Adding auditory input to reading of scientific words was more effective in creating word memory than reading alone.