Contents

Guide

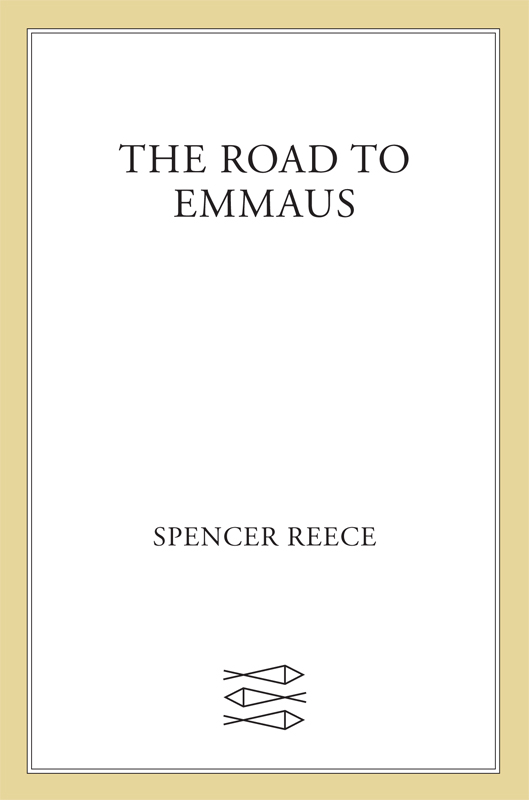

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. Contents I dedicate this book to: my father, Dr. Richard Lee Reece my mother, Loretta Witkins Reece my brother, Carter Straight Reece & Bishop Leo Frade & Dr.

Diana Frade all my love, all my gratitude to two families who believed in me The real difference between God and human beings, he thought, was that God cannot stand continuance. No sooner has he created a season of a year, or a time of the day, than he wishes for something quite different, and sweeps it all away. No sooner was one a young man, and happy at that, than the nature of things would rush one into marriage, martyrdom or old age. And human beings cleave to the existing state of things. All their lives they are striving to hold the moment fast, and are up against a force majeure. Their art itself is nothing but the attempt to catch by all means the one particular moment, one mood, one light, the momentary beauty of one woman or one flower, and make it everlasting.

It is all wrong, he thought, to imagine paradise as a never-changing state of bliss. It will probably, on the contrary, turn out to be, in the true spirit of God, an incessant up and down, a whirlpool of change. ISAK DINESEN, THE MONKEY ICU Those mornings I traveled north on I-91, passing below the basalt cliff of East Rock where elms discussed their genealogies. I was a chaplain at Hartford Hospital, took the Myers-Briggs with Sister Margaret, learned I was an I drawn to E s. In small group I said, I do not like it, the way young black men die in the ER, shot, unrecognized, their gurneys stripped, their belongings catalogued and unclaimed. In the neonatal ICU, newborns breathed, blue, spider-delicate in nests of tubes.

A Sunday of themselves, their tissue purpled, their eyelids the film on old water in a well, their faces resigned in plastic attics, their skin mottled mildewed wallpaper. It is correct to love even at the wrong time. On rounds, the newborns eyed me, each one like Orpheus in his dark hallway, saying: I knew I would find you, I knew I would lose you. THE MANHATTAN PROJECT First, J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote his paper on dwarf starsWhat happens to a massive star that burns out? he asked. His calculations suggested that instead of collapsing it would contract indefinitely, under the force of its own gravity.

The bright star would disappear but it would still be there; where there had been brilliance there would be a blank. Soon after, workers built Oak Ridge, the accumulation of Cemesto hutments not placed on any map. They built a church, a school, a bowling alley. From all over, families drove through the muddy ruts. The ground swelled about the ruts like flesh stitched by sutures. My father, a child, watched the loads on the tops of their cars tip.

Gates let everyone in and out with a pass. Forbidden to tell anyone they were there, my fathers family moved in, quietly, behind the chain-link fence. Niels Bohr said: This bomb might be our great hope. My father watched his parents eat breakfast: his father opened his newspaper across the plate of bacon and eggs, his mother smoked Camel Straights, the ash from her cigarette cometing across the back of the obituaries. They spoke little. Increasingly the mother drank Wild Turkey with her women friends from the bowling league.

Generators from the Y-12 plant droned their ambition. There were no birds. General Leslie Groves marched the boardwalks, yelled, his boots pressed the slates and the mud bubbled up like viscera. My father watched his father enter the plant. My shy father went to the library, which was a trailer with a circus tent painted on the side. There he read the definition of uranium, which was worn to a blur.

My father read one Hardy Boys mystery after another. It was August 1945. The librarian smiled sympathetically at the twelve-year-old boy. Time to go home, the librarian said. They named the bomb Little Boy. It weighed 9,700 pounds.

It was the size of a go-kart. On the battle cruiser Augusta, President Truman said, This is the greatest thing in history. That evening, my fathers parents mentioned Japanese cities. Everyone was quiet. It was the quiet of the exhausted and the innocent. The quietness inside my father was building and would come to define him.

I was wrong to judge it. Speak, Father, and I will listen. And if you do not wish to speak, then I will listen to that. MONACO Monaco was clean, with small clean streets. There was not much in the way of a shore. There was hardly any place to go.

How feminine the tiny cityscape was all whimsical curves and dark, rich cul-de-sacs. So unlike Corsica, its coarse cousin nearby an island of Mafia, sharp rocks, and hairy wild boars that twitched like genitals. Delicate Monaco, how on earth did you protect yourself? Before the Ansbacher bank office, one clipped, well-behaved London plane tree, not welcoming like ordinary trees, was kept apart by a white spear-tipped fence, and had a somewhat diffident sense of noblesse oblige. Through the cream silk brocade window treatments, you could see it: it did not contain birds, repelled the idea of nests, its roots trained and snipped. At night, it was lit. Winds shook the leaves like a showgirls tassels.

In the palace hung a portrait of Princess Graces family, an extravaganza of pastel sfumato by R. W. Cowan, blurring every frail, authentic thing. Surrounded by high cliffs, the air in the principality backed up like in a closet. Lovers smooched on the embankment. The night cross-dressed into dawn.

When the man and woman arrived at the Htel de Paris, the staff assumed they were married. The German Jet Ski instructor was unsure and asked: Are you brother and sister? They paused, demurely, and smiled. The mystery of their bond intensified it. The man and woman were in their late thirties or early forties; they were not young nor were they old. The woman was French and wore a white linen shirt, starched and pressed. She made her money in the drug trade (laundering money from the sale of cocaine or heroin until the money became unrecognizably clean), but all the man knew was that she sold works of art: a Matisse here, a Picasso there her transactions often involving a visit to the Bahamas.

She was what she said she was. But we are rarely what we say we are. They met at a sales counter in Palm Beach where the man was ringing up items at 75 percent off each. She invited him on a trip, after she gave him a sizeable tip. The man, a poor American, meant to say no, but agreed instead. Tall, athletic, effeminate, with a mincing gait, he looked as if he were being chased by something no one could see.

He wore needle-pointed shoes by Stubbs & Wootton and dressed in cashmere and shantung. The broad-shouldered Frenchwoman grimaced, was referred to as handsome. Ample her gestures, ample her need to please; if her tone was not sexual, it came close. The couple exhibited variations the world never embraced, but presented as a couple the world embraced promptly, for the world trusted what was coupled. Both controlled their wonder. Whatever their motives, the navet they displayed hid their intentions.

Skirting promises at a caf, she asked: What shall we name our children, mon petit cheri? They made a myth for everyone to see. One day, similar to all their days, the couple went to the Casino in Monte Carlo. There they met the androgynous Baroness von Lindenhoffer. Many proposed the baroness was lesbian, but of this she never spoke. Some believed her to be a conundrum her muteness alluding perhaps to a hidden passion or a complicated reaction to herself for reasons long forgotten or buried. This might have been true, but just as probable, some thought her shy, an unsuccessful heterosexual who was deeply mannish.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. Contents I dedicate this book to: my father, Dr. Richard Lee Reece my mother, Loretta Witkins Reece my brother, Carter Straight Reece & Bishop Leo Frade & Dr.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. Contents I dedicate this book to: my father, Dr. Richard Lee Reece my mother, Loretta Witkins Reece my brother, Carter Straight Reece & Bishop Leo Frade & Dr.