Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR MELISSA

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at.

OSCAR WILDE

se hace camino al andar.

ANTONIO MACHADO

The corner of Fifth and Elm Streets in Cincinnati, Ohio, has held a certain significance for me since the day I stood there with my parents, as an eight-year-old in 1976, and watched the Cincinnati Reds return to the city after their seven-game victory over the Boston Red Sox in what was, as my father told me then and as I still believe, the greatest World Series ever. I made note of the cross streets where we stood because I felt sure that catching a glimpse of Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and Johnny Bench would be the most important thing that had happened up to that point in my life, and might well be for some time to come.

Ten years later I was scanning the radical thought section of a used bookstore in the town where I had just arrived for college. My eyes fixed on the faded purple spine of a book by George B. Lockwood called The New Harmony Movement. It is a history of this countrys first secular utopian experiment, undertaken in 1825 by the Scottish industrialist Robert Owen in a small Indiana town called New Harmony. The copy I pulled from the shelf was a first edition published in 1905; its cloth cover had been worn smooth, and the gilt lettering on the spine had almost disappeared. Still, there seemed to me something talismanic about the book; it held, after all, a secretthe secret of society. I slowly flipped through its pages until I hit upon this passage: On the 18th of May, 1827, there was unpretentiously opened at the corner of Fifth and Elm streets in Cincinnati a small country store, conducted on a plan new to commerce. It was the first Equity store, designed to illustrate and enact the cost principle, the germ of the cooperative movement of the future. And 149 years later, I would stand at that same corner, the crossroads of utopia, as it turned out, to watch a ticker tape parade for the world champion Reds.

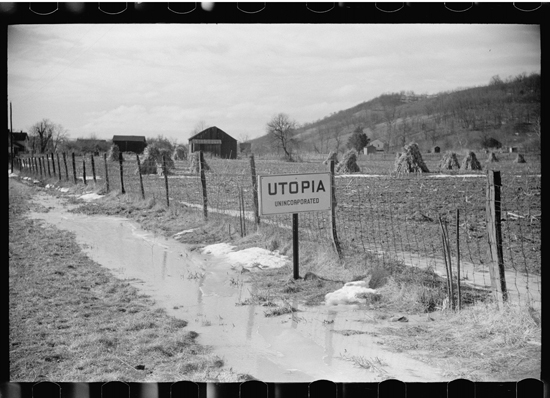

I can point to that afternoon in 1986 when I bought The New Harmony Movement for a few dollars as the first day of my fascination with a strange coterie of nineteenth-century world mendersmen and women such as Robert Owen, Mother Ann Lee, John Humphrey Noyes, Josiah Warren, and otherswho plotted paradise across the eastern United States. From 1820 to 1850, close to two hundred utopian communities sprang to life. In 1840, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote to his British friend Thomas Carlyle, We are all a little wild with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has a draft of a new community in his waistcoat pocket. Commercial employment had grown selfish to the borders of theft, said Emerson, so there was nothing for the virtuous American to do but begin the world anew. It was, after all, a very young country. Such things seemed possible. Whats more, the religious revivals that stirred unexpected foment at the beginning of the nineteenth century convinced many men and women that Christs Second Coming was imminent and they had better start preparing an earthly kingdom. Many secular utopias were a response to the economic Panic of 1837, when, much as in 2008, reckless speculation sank banks and plunged the country into a prolonged depression. As a result, a number of Americans fled urban life and went looking for more just and compassionate ways to organize human affairs. Others simply saw communal living and sharing as a means to better realize the countrys founding principles; in the United States of the early 1800s, the newly coined word socialism carried none of the heretical freight it does today. What these communities all took up, in one form or another, was an experiment in radical idealism.

Two decades later, the Civil War brought most of those experiments to an end. But contrary to the common perception, the majority did not fail because their founding principles proved nave, or overly optimistic, or contradictory to the inalterable selfishness of human nature. In fact, many were great successes, and their stories have been obscured only by the larger American story of a union preserved, slavery abolished, and the rise of an industrial economy. That economy also helped to crush the utopian movement in this country, and it ultimately created an American consumer culture so unsustainable and so devoid of idealism that we now stand on the verge of both environmental calamity and an intractable federal plutocracya government given over to the rich by a bewildered, defeatist populace. Americans live in a world we are too ready to accept. We acquiesce too easily to the inevitability of the way things are. Indeed, many of us think of our consumer culture as its own version of utopia, where we are absolved of the responsibility to question where our food, our clothes, our cellular devices, our energy come from. Of course an astonishing amount of cruelty and violence makes this utopia possiblea violence done to the land, a violence done to human and nonhuman life.

To resist, or at least escape for a while that air of inevitability, I began to conceive in my mind a road trip through this countrys alternate economic and social historyits utopian past. For twenty-five years, I had been casually reading and collecting materials about those nineteenth-century visionaries. Last October, I finally felt ready to go. With a map of the eastern United States spread out across my kitchen table, I plotted my prospective route with a green marker. It would start right down the road from me, at the site of a Shaker community called Pleasant Hill, and it would end in Oneida, New York, where the perfectionists, led by John Humphrey Noyes, invented a free-love philosophy called Bible communism, which was at once the opposite and the apotheosis of the chaste Shakers. My plan was to pick through the ruins and the reconstructions of those utopian dreams in the hope of piecing that story back together. I wanted to examine those remains to find what images and ideas might be exhumed and perhaps breathed back to life. The economist Milton Friedman, who was wrong about a great many things, was right, I think, when he said, Only a crisisactual or perceivedproduces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable. Because I believe our country is in the midst of great political, economic, social, and environmental crises, I decided to set out in search of those alternatives that now seem impossible but might soon prove inevitable.

I will not, of course, visit every utopian community that ever took shape in this country, and the account that follows is in no way meant to present a comprehensive history of the American utopian movement. Im not a social scientist; Im a guy with a truck, a gas card, and a few boxes of old books shifting around in the cab. In fact, I made a deliberate decision to limit my peregrinations to the eastern states. That leaves out communities and movements such as the Mormons of Utah, the Icarians of Iowa, Colorados Drop City, and Paolo Soleris ecotopia, Arcosanti, in the Arizona desert. Among others. This, unfortunately, could not be helped. I am afflicted by a bizarre mental illness whereby the analytical portion of my brain stops functioning whenever I cross the Mississippi River. While its all fascinating out there, out west, Ive spent my whole life in the eastern United States, and as a result, I dont trust my instincts to read the western geographical and cultural landscapes with any real sense of understanding or acuity. But more than that, of the two hundred or so utopian communities that formed between 1820 and 1850, almost all of them took root in the eastern half of this young country. It was here in the East that preachers, publishers, and backwoods prophets began the hard mental and physical work of conceiving paradise on earth. Many of those visionaries eventually wandered or were forced westward, but the elemental intellectual history of the utopian movement still lies, or is buried, on Long Island, in upstate New York, or on the banks of the Wabash River in Indiana. Beginning near the latter and roving east toward the former, I suspect there will be plenty to see.