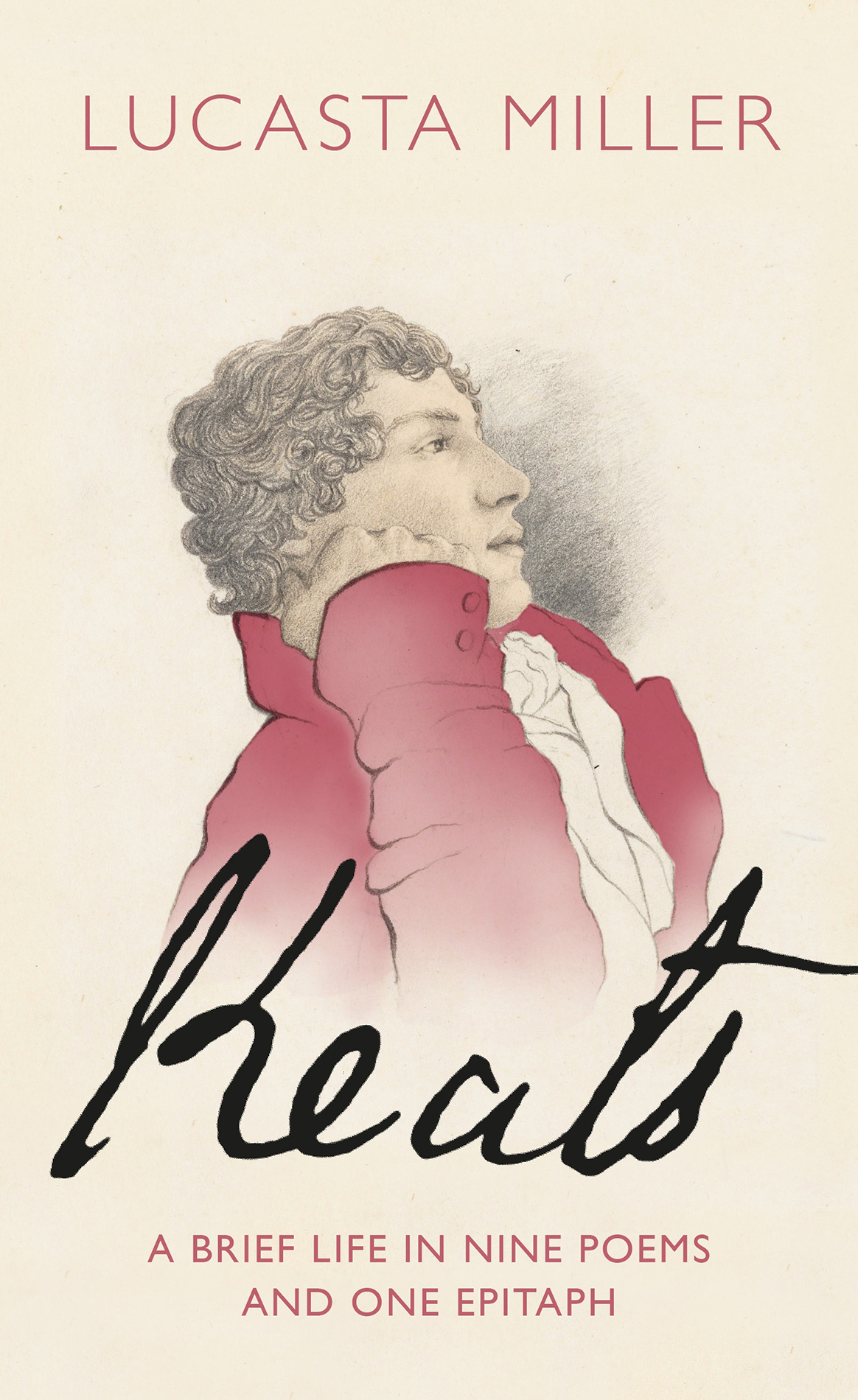

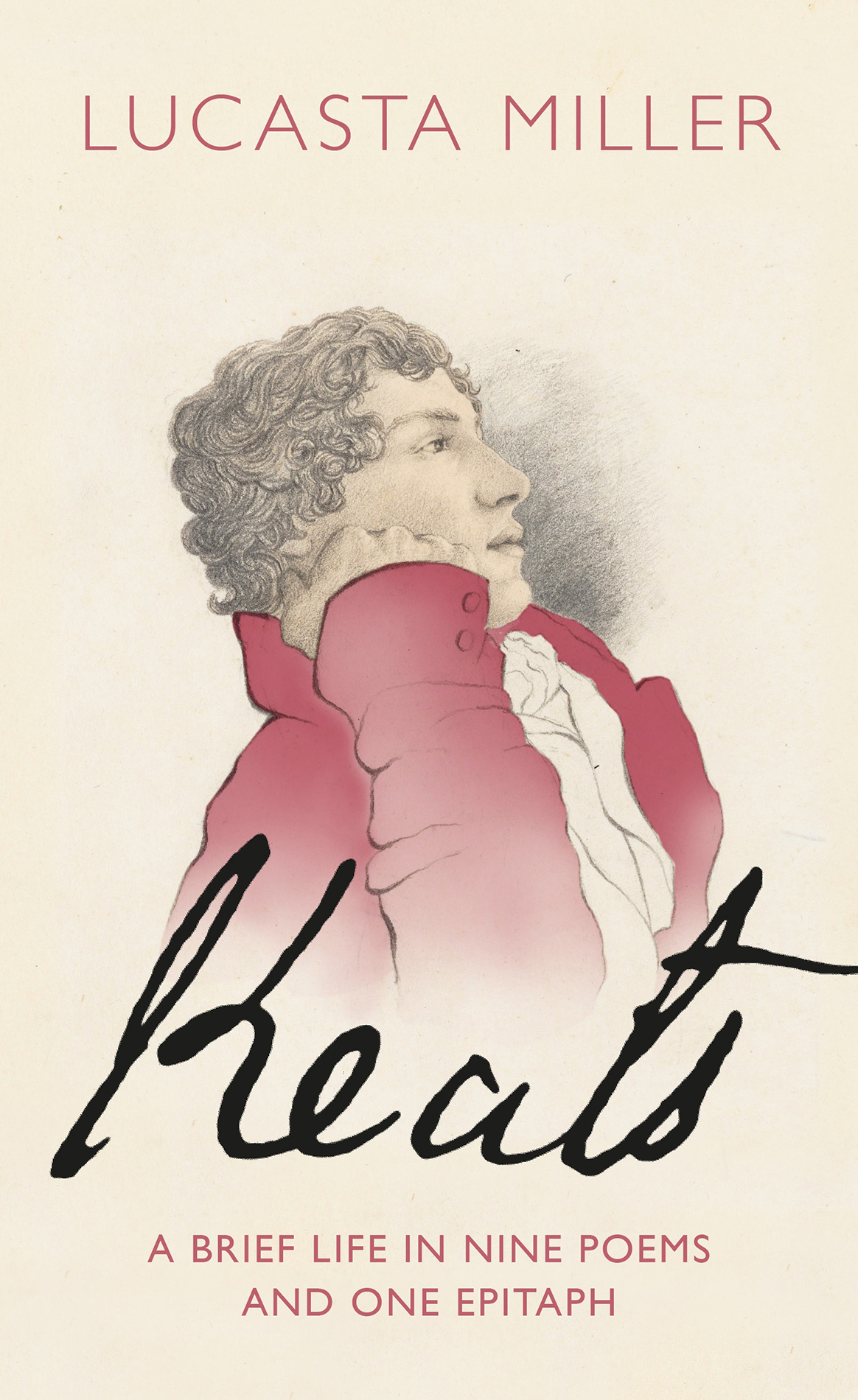

Lucasta Miller

KEATS

A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph

CONTENTS

About the Author

Lucasta Miller is a biographer and critic, whose articles have appeared in a wide number of publications, especially the Guardian. She is the author of two previous books on nineteenth-century literature, The Bront Myth and L.E.L.: the Lost Life and Mysterious Death of the Female Byron, and is currently an Honorary Research Associate at University College, London and a Royal Literary Fund Fellow.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Bront Myth

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Mysterious Death of the Female Byron

To my mother

List of Illustrations

L IFE MASK OF J OHN K EATS by Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1816 (Alamy)

P ROFILE DRAWING OF K EATS by Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1816 ( National Portrait Gallery, London)

K EATS, MINIATURE by Joseph Severn, 1819 (Alamy)

P ERCY B YSSHE S HELLEY by Amelia Curran, 1819 (Alamy)

K EATS ON HIS DEATHBED by Joseph Severn, 1821 (Keats House, Hampstead, London / Bridgeman Images)

M ANUSCRIPT OF O DE TO A N IGHTINGALE , 1819 (Alamy)

K EATS L ISTENING TO A N IGHTINGALE ON H AMPSTEAD H EATH by Joseph Severn, 1845 (Alamy)

F ANNY B RAWNE, MINIATURE by an unknown artist circa 1833 (Alamy)

W ENTWORTH P LACE, NOW K EATS H OUSE (photograph: C.F.B. Miller)

W ESLEYAN P LACE (authors photograph)

K EATSS GRAVE (authors photograph)

Prologue

Body and Soul

T HIS IS A book by a reader for readers. It takes nine of Keatss best-known poems the ones you are most likely to have read and excavates their backstories. Reproduced at the beginning of each chapter, the poems are arranged chronologically in the order in which Keats wrote them. They are used as entry points into telling his life story, although this is not quite a conventional biography. Instead, my aim has been to get under the skin of those now famous poems, to see how he made them and to answer the questions about them, and him, that have always intrigued, inspired or irked me. The close readings are my own, but they are informed by a long tradition of Keats scholarship and draw on the most recent research.

I want, in this two-hundredth anniversary of his death, to foreground those aspects of the poets life and work that havent always made it into the popular imagination, which still tends to make him appear rather more ethereal than he actually was. Its hard, for example, to imagine that the Keats in the award-winning romantic biopic Bright Star (2009) which focuses chastely on his relationship with Fanny Brawne, with whom he fell in love towards the end of his short life could have taken medication for syphilis. Or that he could have had radical and heterodox political and religious opinions. Or that he had experienced a painfully dysfunctional childhood, taken drugs, inserted a scalpel into a mans head or extracted a bullet from a womans neck. Or that he had gone on to die with his lungs so ravaged by tuberculosis that the doctors who performed the autopsy could not believe he had lived as long as he had.

Most importantly, the film does not explain how he could have grabbed established English verse by the scruff of its neck and shaken it into something utterly fresh, while inventing strange new words, such as surgy, palely, soother, adventuresome; and creating phrases, including tender is the night, negative capability, and A thing of beauty is a joy for ever, that went on to have an afterlife divorced from their original context. According to one critic at the time, Keats rejected prescriptive language in pursuit of his own originality. His contemporaries bridled. In 1820, the Literary Chronicle and Weekly Review complained that Keatss work was unintelligible and urged him to avoid coining new words. For that reason, the London Magazine opined that some might regard him as a subject for laughter or for pity. Keats has had the last laugh.

The urge to imagine dead poets into life is something that John Keats understood. On the evening of Friday 12 March 1819, he depicted himself in the momentary act of writing, as he scribbled a new instalment in a long journal-letter, written over several weeks between 14 February and 3 May, to his brother George and sister-in-law Georgiana, who had recently emigrated to America:

the candles are burnt down and I am using the wax taper which has a long snuff on it the fire is at its last click

I am sitting with my back to it with one foot rather askew upon the rug and the other with the heel a little elevated from the carpet Could I see the same of any great Man long since dead it would be a great delight: as to know in what position Shakespeare sat when he began To be or not to be.

We cant satisfy Keatss curiosity about Shakespeare, but this vignette brings John Keats himself vividly and, to posterity, voyeuristically to life. He was twenty-three at the time and, though he didnt know it, had a little less than two years to live.

Nothing much has surfaced about Shakespeares day-to-day existence since 1819, even after a further two hundred years of increasingly in-depth scholarship. Although the posthumous impact of his works on culture including, electrically, on Keats himself is more recorded and expansive than that of any other English writer, Shakespeare the man remains resolutely disembodied, despite the efforts of his biographers, owing to the lack of surviving contemporary letters and diaries. His context can and has been reconstructed in ever more fascinating detail, but Shakespeare as a subjective individual remains for us a non-entity. He indeed seems the ultimate chameleon poet, as Keats put it, who has no self (or camelion Poet to quote Keats in his original spelling, which is often quite idiosyncratic, as is his punctuation).

We have a lot more detailed, time-specific, personal information about John Keats. We know, for example, exactly where he was when he wrote to George and Georgiana, by the dull light of a taper and with his back to the fire: at Wentworth Place, the house on the edge of Hampstead Heath where he was then living as the lodger of his friend Charles Armitage Brown. Its now a museum called Keats House. You can visit it today and see the very fireplace where those dying embers clicked.

These days, Keats House sits on a street renamed Keats Grove in which the other houses are now prestigious properties, affordable only by international bankers, from which most twenty-something writers in the London area would be priced out. Its a world away, economically, from that of the insecure Regency middle class to which Keats and his friends belonged, though the instability they lived through was not that far away from the experience of todays urban millennials.

In 1819, Keats House was a pretty but modest suburban new-build, finished less than three years before he moved in, and architecturally a bit of a cheat. From the front, it looked like a symmetrically proportioned single villa, with a central front door and windows either side, like a childs drawing of what a house should look like. But the facade hid the fact that it was designed on the inside to house two small independent semi-detached dwellings, divided by a party wall, each with its own individual staircase: a symptom of the way in which Regency taste often had more to do with aspirational appearance than reality. In the later nineteenth century, the house was remodelled. The front door used by Brown and Keats which was round the side no longer exists; nor does their staircase. But the rooms where they lived each had a study on the raised ground floor and a bedroom above are the same.

Next page