CONTENTS

Contents

Guide

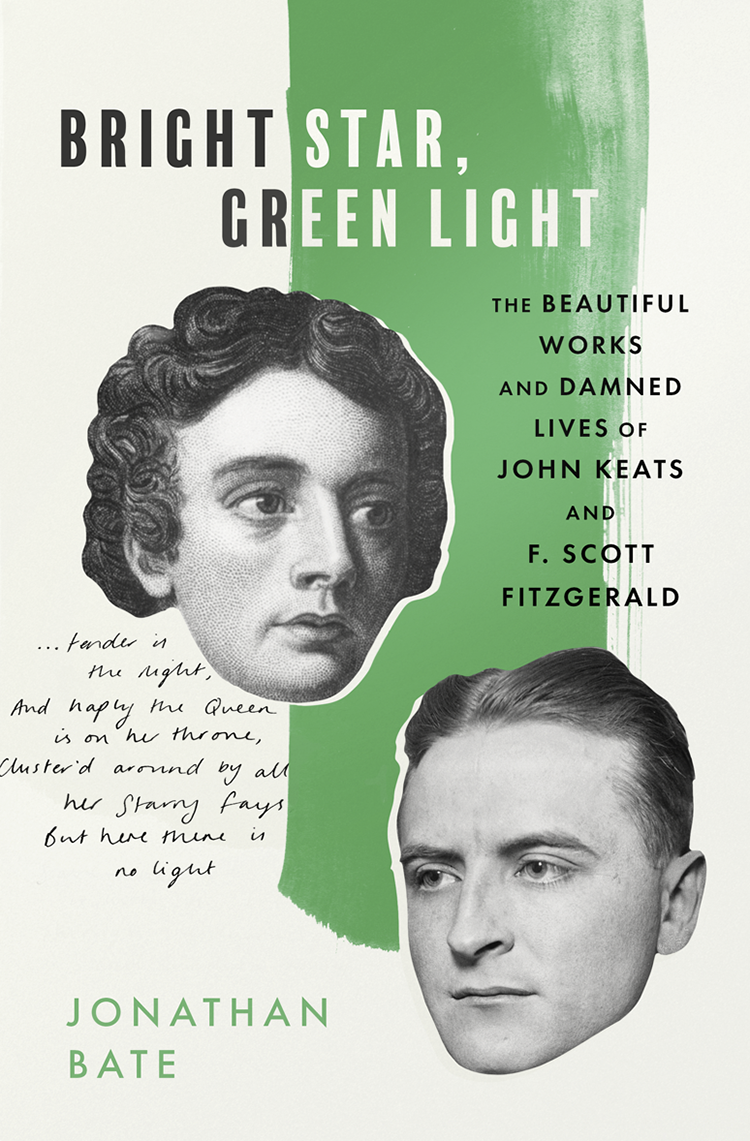

BRIGHT STAR

GREEN LIGHT

THE BEAUTIFUL WORKS AND DAMNED LIVES OF JOHN KEATS AND F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

Jonathan Bate

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

Copyright Jonathan Bate 2021

Cover images Bettmann/Contributor/Getty (Fitzgerald),

Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty (Keats)

Jonathan Bate asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008424978

Ebook Edition January 2021 ISBN: 9780008424985

Version: 2021-01-27

For

Philip Davis, boat against the current

&

Kelvin Everest, Keatzian

& in memory of Miriam Allott

The author and publishers are committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others and have made all reasonable efforts to trace the copyright owners of those images reproduced in this book that are not in the public domain, and to provide appropriate acknowledgment here. In the event that any untraceable copyright owners come forward after the publication of this book, the author and publishers will use all reasonable endeavours to rectify the position accordingly.

Biography is the falsest of the arts. That is because there were no Keatzians before Keats

(F. Scott Fitzgerald, undated notebook entry)

I have lovd the principle of beauty in all things

(John Keats, letter to Fanny Brawne, February 1820)

Beauty of great art, beauty of all joy, most of all the beauty of women

(F. Scott Fitzgerald, This Side of Paradise)

I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death

(John Keats, letter of 14 October 1818)

thinking of my ambitions so nearly achieved of being part of English literature

(F. Scott Fitzgerald, letter of summer 1930)

The artist is the creator of beautiful things. To reveal art and conceal the artist is arts aim.

The critic is he who can translate into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful things.

(Oscar Wilde, preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890)

A little before Christmas 1818, John Keats wrote from the village of Hampstead, just outside London, to his brother and sister-in-law George and Georgiana. They were 4,000 miles away in the log cabin of the ornithologist John James Audubon in Henderson, Kentucky. They had a wild turkey nesting on the roof, a household of children and a boisterous pet swan called Trumpeter to keep them company. Keats was alone with his grief, writing with the news about their other brother that they had been dreading for months: of poor Tom were of the most distressing nature. Tuberculosis had taken him.

Keats comforted himself with the thought that he had of immortality of some nature of other. Of other was a slip of the pen for or other, but perhaps a telling one in that Keats conceived of immortality as a connection to others rather than something to do with God and heaven. That will be one of the grandeurs of immortality, he continued, there will be no space and consequently the only commerce between spirits will be by their intelligence of each other. The immortals will completely understand each other while we in this world merely comprehend each other in different degrees. Mutual comprehension, he suggests, is the measure of love and friendship. He did not feel so very distant from George and Georgiana, despite their emigration to America, because he could remember every detail of their manner of thinking and feeling, the shaping of their joys and sorrows, their ways of walking, standing, sauntering, sitting down, laughing and joking.

In order to demonstrate their connection, he proposed that he should read a passage of Shakespeare every Sunday morning at ten oclock and that they should do so at the same time. Shakespeare would bring them as near each other as blind bodies can be in the same room. This experiment in quasi-telepathy via shared simultaneous reading would, presumably, have been stymied by the difference in , he said, show like the hieroglyphics of beauty; his ambition was to join them in what he called an immortal freemasonry. The endurance of great art was the only immortality of which he was certain.

George and Georgiana had eight children, including a son named John Keats, who became a civil engineer in Missouri. He lived until 1917. A report in a Minnesota newspaper had once predicted that will probably die with him. But by 1917 the name of Keats was truly among the immortals. It lived through those who read and loved his work, such as a Princeton student from St Paul, Minnesota, who that very year was immersing himself in poetry, beginning his first novel, and yearning for a green light from the girl of his dreams.

*

Biographers and critics have noted that John Keats was F. Scott Fitzgeralds favourite author. have been written about particular passages in his novels where the relationship becomes apparent. But the full extent of the influence, its pervasiveness across Fitzgeralds career, the sense that he saw himself as the prose Keats, remains underappreciated.

The parallels between their lives are uncanny. Each of them established themselves as authors in the aftermath of a long and devastating war. Each lived in a time of freedom and experimentation that came to an abrupt end with a financial crisis: the stock-market panic of 1825 and the Wall Street crash of 1929. Each sought to supplement the work that was their vocation poetry in Keatss case, prose fiction in Fitzgeralds by trying to make money in the more lucrative arena of the performing arts: Keats writing for the London stage, Fitzgerald for the Hollywood screen.

Keatss last years were shadowed by his unconsummated love for Fanny Brawne, for whom he wrote his most famous sonnet, Bright Star. Fitzgeralds writing was shadowed by his unconsummated love for Ginevra King, who inspired the character of Daisy Fay in The Great Gatsby. In their literary taste, both were borne back ceaselessly into the past: Keats to the romance of the Middle Ages and to the English poetry that he loved (Milton, Shakespeare); Fitzgerald, to Keats.

Keatss imagination was fired to life by Shakespeare, but he failed when he tried to write pseudo-Shakespearean blank-verse drama. He succeeded, triumphantly, when he took the spirit of Shakespeare and infused it into a different form, that of lyric poetry the ode, above all. F. Scott Fitzgeralds imagination was fired to life by Keats, but he failed when he tried to write pseudo-Keatzian lyric poetry. He succeeded, triumphantly, when he took the spirit of Keats and infused it into a different form, that of the lyrical novel