LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

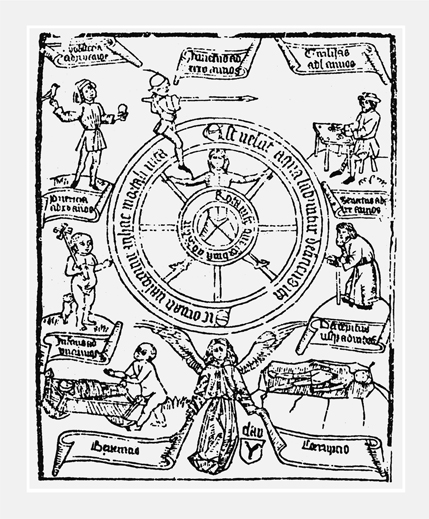

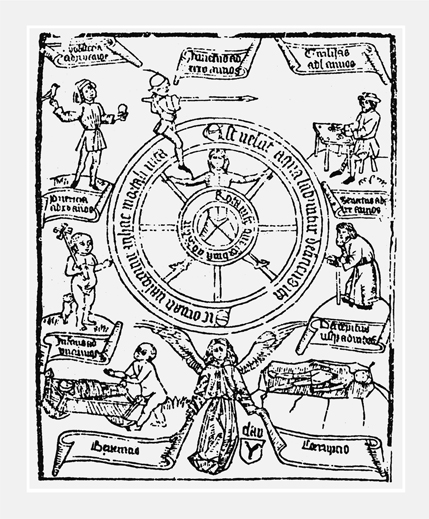

1. The Seven Ages of Man: fifteenth-century German woodcut. BPK Images

2. Portrait of a child aged four years, 1572. Private collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

3. Engraving after the Ditchley portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Author's private collection.

4. Christopher Saxton's map of England and Wales, 1579. Royal Geographical Society, London/The Bridgeman Art Library.

5. Close-up of Shakespeare country from Saxton's map of Warwickshire and Leicestershire, 1576. Author's private collection.

6. Frontispiece to Michael Drayton's Polyolbion, 1612. Author's private collection.

7. Thomas Digges, A Perfect Description of the Celestial Orbs, 1576. The Wellcome Library, London.

8. Frontispiece to John Case's Sphaera Civitatis, 1588. Author's private collection.

9. A Tudor schoolroom. Private Collection/The Bridgeman ArtLibrary.

10. A page from the Geneva Bible, 1560. Author's private collection.

11. Portrait miniature by Nicholas Hilliard. Victoria and AlbertMuseum, London/The Bridgeman Art Library.

12. A seething bath: cure for syphilis. Wellcome Library, London.

13. The sons of Philip Herbert as painted by Sir Anthony Van Dyck. Collection of the earl of Pembroke, Wilton House, Wiltshire/The Bridgeman Art Library.

14. John Davies of Hereford, 1633. National Portrait Gallery, London.

15. Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex. Private collection, the Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

16. Title page of Thomas Heywood's Armada play.V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum.

17. Portrait of the ambassador of the king of Barbary. University of Birmingham Collections.

18. The Lawyer, wooden trencher.Victoria and Albert Museum, London/The Bridgeman Art Library.

19. Pantalone from the commedia dell'arte. Muse des Beaux-Arts, Berbers, France/Giraudon Collection; the Bridgeman Art Library.

20. Robert Armin, 1609.Author's private collection.

21. Mortui divitiae: an emblem of death from Geffrey Whitney, A Choice of Emblemes, 1586. Author's private collection.

22. The First Folio, 1623 (by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library).

INTRODUCTION

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress' eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon's mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances.

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

THE SEVEN AGES OF MAN: A FIFTEENTH-CENTURY GERMAN WOODCUT, WITH THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE IN THE CENTER.

He was not of an age, but for all time! So wrote Ben Jonson in the poem of praise published in the First Folio of collected plays by his friend and rival William Shakespeare. My earlier book The Genius of Shakespeare took that claim seriously and suggested that what we mean by Shakespeare is not just a life that lasted from 1564 to 1616. We also mean a body of words, characters, ideas, and stage images that have remained alive for four centuries because of their endless capacity for renewal and adaptation through the work of succeeding generations of actors and spectators, appreciative readers, and creative artists in every conceivable medium.

In the same poem Jonson also described Shakespeare as Soul of the age. In this book, I turn to that claim, taking it equally seriously. The Elizabethans regarded the soul as the principle of life: through his works, Shakespeare gives life to his age. In trying to imagine what Jonson meant by his claim, we need to ask both, What was it like being Shakespeare? and, What are the most telling ways in which Shakespeare's works embodyor rather ensoulthe world-picture of his age? We have to shuttle back and forth between the Shakespearean mind and what has been usefully called the Shakespearean moment. Shakespeare's uniqueness must be held in balance with his typicality.

Both not of an age and Soul of the age. For Ralph Waldo Emerson, writing in nineteenth-century New England, Shakespeare was inconceivably wise, possessed of a brain so uniquely vast that no one can penetrate it. But at the same time, he was the incarnation of a cause, a country, and an age. It is this double quality that makes Shakespeare, in Emerson's fine phrase, the