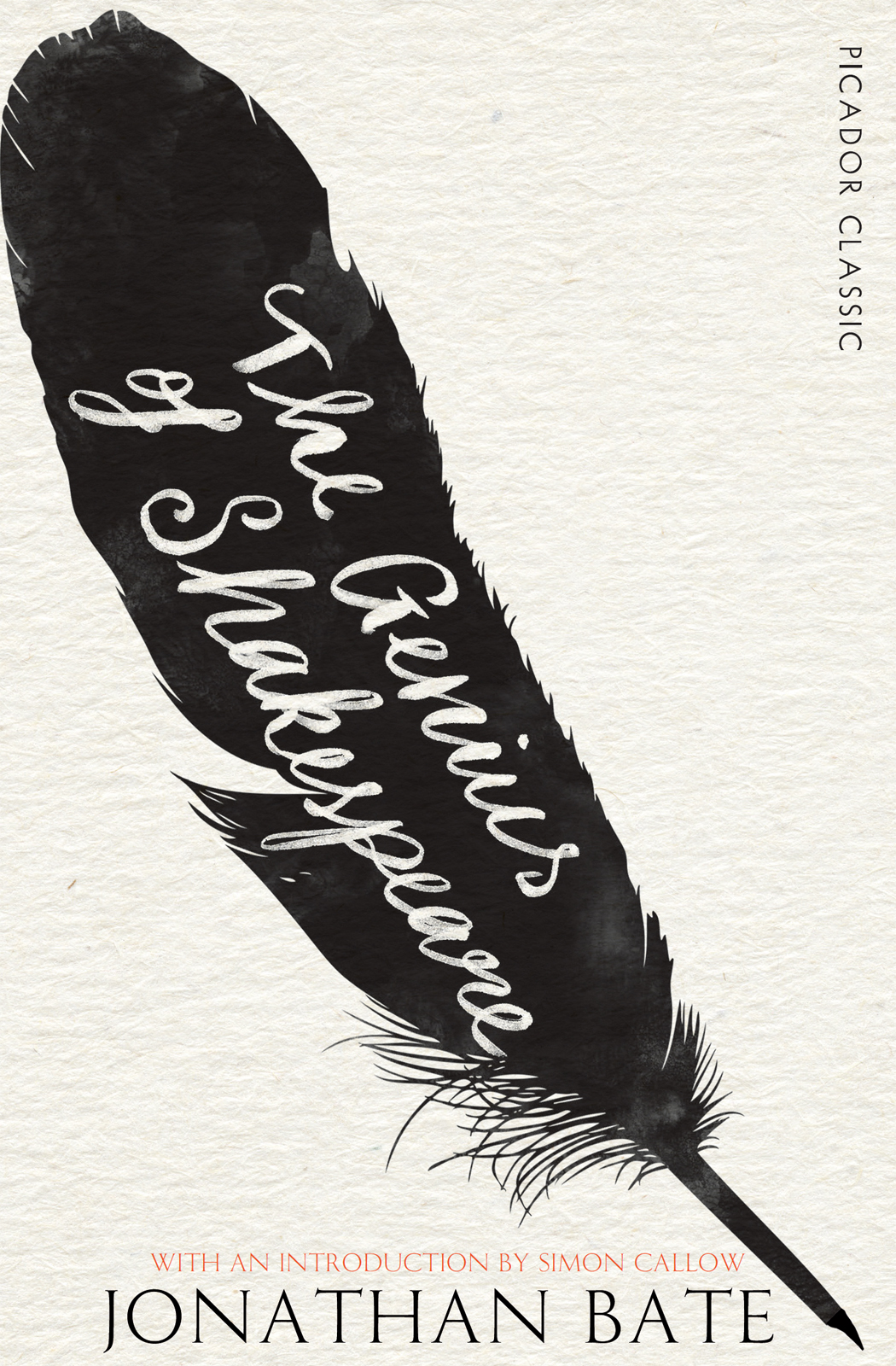

Bate Jonathan - The Genius of Shakespeare

Here you can read online Bate Jonathan - The Genius of Shakespeare full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2013, publisher: Picador Classic, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Genius of Shakespeare

- Author:

- Publisher:Picador Classic

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:London

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Genius of Shakespeare: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Genius of Shakespeare" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Genius of Shakespeare — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Genius of Shakespeare" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

S HAKESPEARE S A UTOBIOGRAPHICAL P OEMS ?

Brief lives

The first biographies of Shakespeare were anecdotal. In his Brief Lives, John Aubrey recorded that the dramatists father was a butcher and that the boy William used to help him in the family shop, killing calves in a high style to an accompanying dramatic speech. Aubrey also reported that between leaving school and becoming a player in London, William was himself a country schoolmaster. And he said that he had been told that during Shakespeares working life in London the dramatist returned to his native Stratford once a year, stopping off in Oxford at a tavern owned by a Mr and Mrs Davenant, the latter being a witty and beautiful woman who just might have borne him an illegitimate son who grew up to be Sir William Davenant, Poet Laureate.

Like the anecdotes from Shakespeares own lifetime, each of these three items of gossip has symbolic meaning. The first attests to his humble and rural origins. It sows the seed for the excesses of later Bardolatry: the butchers son from provincial Stratford has the same kind of background as the carpenters son from provincial Nazareth. After God, said the Romantic novelist Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte-Cristo, Shakespeare created most. The second anecdote contributes to the long debate about whether Shakespeares genius was a matter of nature or art. The schoolmastering story had fairly good authority, in that it came from the actor William Beeston, whose father was the actor Christopher Beeston, a member of Shakespeares company. Aubrey introduced it specifically in order to modify Ben Jonsons small Latin and less Greek. The third piece of gossip serves the dual purpose of suggesting that Shakespeare was a bit of a lad and making him the father of later creative endeavour. Davenant, especially after a few drinks, seems positively to have encouraged the story about his origins: he thought it was worth impugning his mothers good name for the sake of establishing his own poetic pedigree. The royal imprimatur of Davenants Laureateship is symbolically passed back to Shakespeare, who thus begins his long career as Englands National Poet.

After Aubrey came Nicholas Rowe. Though more substantial than anything that had gone before, and formally billed as Some Account of the Life of Mr William Shakespear, his biography, prefaced to his 1709 edition of the Works, was still anecdotal rather than documentary. Rowe begins by saying that his prime interest is the kind of little Personal Story which brings colour to the life of a great man. This Life gave currency to such memorable anecdotes as the deer-stealing incident Shakespeare the lad once more and the casting of William himself as the ghost of Hamlets father. The latter lays the ground for later readings of Hamlet as the dramatists most favoured son among all his characters a reading reinforced by the discovery that Shakespeare really did name his son Hamnet, which appears to be a variant of Hamlet.

The eighteenth century is full of narratives, both historical and fictional, of men who rose from low to high in English society. Rowes Shakespeare is just such a man. He begins by offending against the Game Laws, which in Rowes time remained one of the primary means of protecting the property rights of country gentlemen; he is drummed out of town by Sir Thomas Lucy, the local landowner, and, like Dick Whittington or Henry Fieldings Tom Jones, is forced to go to London to seek his fortune. He ends up hobnobbing with the rich and famous:

He had the Honour to meet with many great and uncommon Marks of Favour and Friendship from the Earl of Southampton... There is one instance so singular in the Magnificence of this Patron of Shakespears, that if I had not been assurd that the Story was handed down by Sir William DAvenant, who was probably very well acquainted with his Affairs, I should not have ventured to have inserted, that my Lord Southampton, at one time, gave him a thousand Pounds, to enable him to go through with a Purchase which he heard he had a mind to.

He even attracts the attention of the Queen herself:

Queen Elizabeth had several of his Plays Acted before her, and without doubt gave him many gracious Marks of her Favour... She was so well pleasd with that admirable Character of Falstaff, in the two Parts of Henry the Fourth, that she commanded him to continue it for one Play more, and to shew him in Love. This is said to be the Occasion of his writing The Merry Wives of Windsor.

This tradition of a royal command was first recorded by John Dennis in the preface to his adaptation of The Merry Wives of Windsor, published in 1702. He added for good measure that the Queen was so keen to see Sir John in love that she gave Will just ten days to write the play and he duly obliged.

The anecdote retains its point whether or not the commission came from the Queen: Shakespeare is imagined to have the gift of dashing off a new play in less than a fortnight, while Falstaff is made into a larger-than-life character who bursts the bounds of the play in which he originally appeared. He generates not only a second part of Henry IV, but also The Merry Wives. We cannot have enough of Falstaff, so what better than a play which shows him in love? One of the first things we want to know about our heroes is who they fell in love with.

Shakespeare unlocks his heart?

What, then, about the love life of Shakespeare himself? Rowe and his successors among the eighteenth-century Shakespeareans did not take much interest in the question, though they repeatedly returned to the anecdote about Davenant being the dramatists natural son. It certainly did not occur to them to seek in the plays for hidden clues to Shakespeares amorous inclinations. They did not regard literature as encoded autobiography. This was an idea which only emerged towards the end of the century and which was at the centre of the great cultural shift that we call the Romantic movement.

The point is crucial and a failure to grasp it has done more than anything else to create misconceptions and myths about Shakespeare. In a book on Sir Philip Sidney, John Buxton provides the best summary I know of the cardinal difference between late sixteenth- and early nineteenth-century poetry:

The Elizabethans wrote for Penelope Devereux, or Lucy Harington, or Magdalen Herbert, for a gentleman or noble person, for the court, for the benchers of the Middle Temple. Their audience was not vaguely perceived through a mist of universal benevolence: they could kiss its hand, or hear the tones of its voice. From this arises the paradox that the Romantics, writing for the patronage of the unknown man in the bookshop, are much more personal than the Elizabethans, writing, as often as not, for someone with whom they had dined a few days ago. For the Romantic, with everyone to write for, and therefore with no one to write for, wrote for and about himself in a way unprecedented in literary history, as Wordsworth remarked; whereas the Elizabethan tried to produce a poem to suit a particular occasion and a known taste.

Scorn not the sonnet, wrote Wordsworth in his sonnet on the sonnet: with this key / Shakspeare unlocked his heart. Did Shakespeare? answered Robert Browning, who knew the habits and conventions of the Renaissance, the arts of persona and role-play, rather better. If so, the less Shakespeare he!

When Romantics get their hands on Shakespeares sonnets, the trouble begins. In 1796 August Wilhelm von Schlegel, a central figure in the German Romantic movement, remarked that the sonnets appeared to have been inspired by real love and therefore gave unique access to the poets life. In his lectures on drama delivered in Vienna in 1808, he amplified the point:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Genius of Shakespeare»

Look at similar books to The Genius of Shakespeare. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Genius of Shakespeare and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.