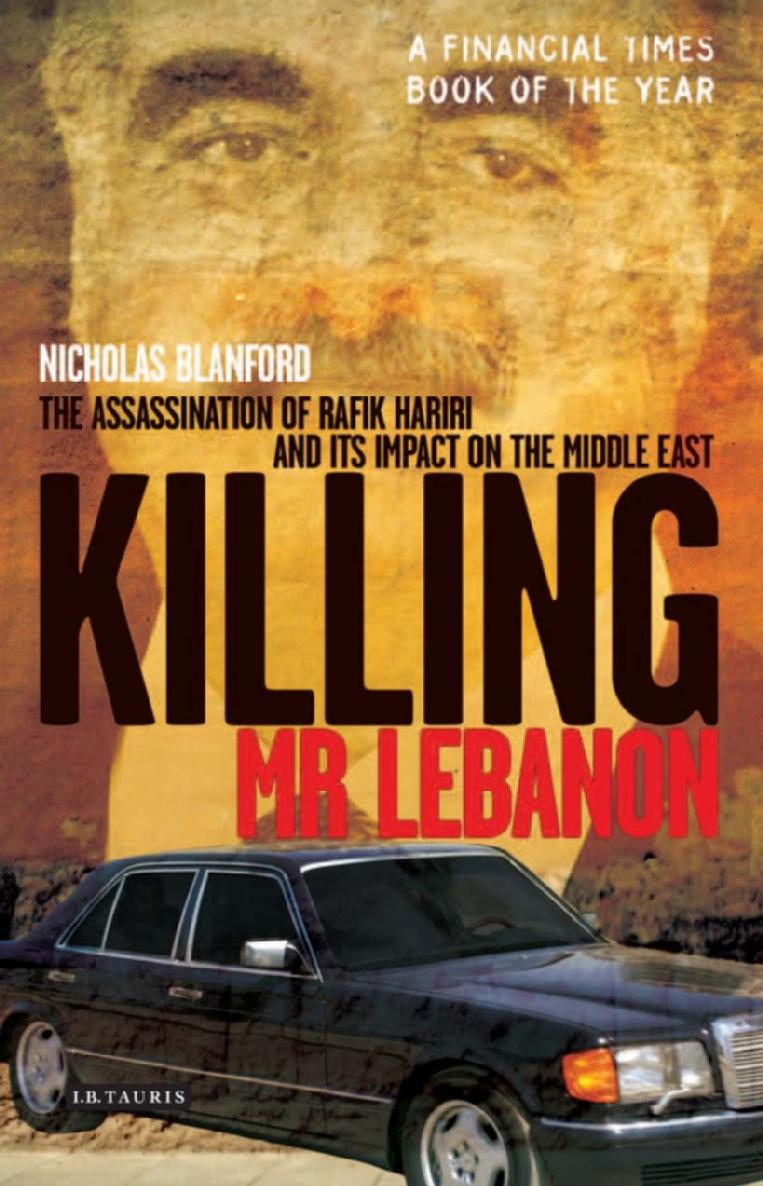

Killing Mr Lebanon

Killing Mr Lebanon

The assassination of Rafik Hariri and itsimpact on the Middle East

Nicholas Blanford

Published in 2006 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

In the United States of America and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St. Martins Press 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright Nicholas Blanford, 2006

The right of Nicholas Blanford to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 10: 1 84511 202 4 HB

ISBN 13: 978 1 84511 202 8 HB

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available Typeset in Palatino by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by

TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

C o n t e n t s

P r e f a c e

v i i

C H A P T E R O N E

C o u n t d o w n

C H A P T E R T W O

T h e F i x e r

1 3

C H A P T E R T H R E E

P a x S y r i a n a

4 0

C H A P T E R F O U R

T h e B r e a c h

7 1

C H A P T E R F I V E

S h o w d o w n

1 0 0

C H A P T E R S I X

T h e B e i r u t S p r i n g

1 2 8

C H A P T E R S E V E N

A N e w L e b a n o n ?

1 7 4

C H A P T E R E I G H T

E p i l o g u e : T h e R e t u r n o f W a r 2 1 2

N o t e s

2 2 0

I n d e x

2 3 1

P r e f a c e

I was working at home when the explosion that killed Rafik Hariri blasted through my quiet neighbourhood two kilometres from the St George Hotel, rattling windows and sending a few loose panes of glass smashing onto the street outside. I telephoned my United Nations peacekeeping contacts in south Lebanon, assuming that the thunderclap was produced by an Israeli Air Force jet flying a low-level supersonic run over Beirut, a muscle-flexing gesture that often meant trouble along Lebanons southern border with Israel. But all was quiet in the south, they said, although they were hearing from their colleagues in Beirut that there was smoke rising from the hotel district on the downtown seafront.

Minutes later I was waving my Lebanese press card and pushing through the cordon of soldiers who were trying to seal off the site of the explosion. I had driven past the St George Hotel just an hour earlier with my wife and two children, a routine Monday morning trip to the Hamra shopping district in the western half of the city. But the carnage and chaos on the street outside the St George was anything but routine. For many in the West, the name Beirut may still conjure images of Hobbesian violence, but not for me. Beirut had been my home for over a decade. The 16-year civil war had ended in 1990, four years before I moved to Lebanon.

Although blood continued to be shed throughout the 1990s in the stony hills and wadis of the south where Hizbullahs resistance fighters battled Israeli occupation forces, Beirut was a city at peace. Watching the firemen gently pry loose blackened, rubbery corpses from the smoking shell of a car and trying not to trip over the chunks of asphalt and clods of earth littering the road while blinking away the tears brought on by the acrid smoke, I was reminded not of Beirut but of Baghdad, or one of the bloodier days in south Lebanon in the 1990s.

There were only two people who could warrant a bomb assassination of this magnitude, so I thought Walid Jumblatt, the head of the most

viii

Preface

prominent Druze dynasty and outspoken critic of Syrias long hegemony over Lebanon, or Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hizbullah. But Nasrallah rarely left his stronghold in the southern suburbs of Beirut, and the Beirut hotel district was an unlikely location to dispatch the leader of Hizbullah.

It was Mohammed Azakir, a veteran photographer for Reuters news agency, who told me. With an anguished look on his face, he said They got Hariri.

Hariri? Gone? Impossible.

When I arrived in Lebanon, Rafik Hariri had been prime minister for two years, and his larger-than-life presence dominated the country. His national reconstruction programme was moving into action and Solidere, the private company reconstructing the city centre, had just begun dynamiting the war-scarred ruins of the old downtown. His energy and enthusiasm were obvious. When he opened the brand new Beirut International Airport terminal in 1998, I was one of a pack of reporters hurry-ing after Hariri as he marched around the empty gleaming halls and corridors, his entourage struggling to match his pace. Every now and then, he would stop to examine a new luggage conveyor belt, snip a ribbon, smile for the photographers and then march on. One could almost sense him mentally ticking off the airport from his list of things to do.

In interviews, Hariri would give stock answers to political questions such as the LebanonSyria relationship or the resistance war in south Lebanon. But switch the conversation to reconstruction, and his eyes would light up. In 1996, in one of my interviews with Hariri, I asked him how he saw Lebanon at the turn of the century. This was the sort of question Hariri loved.

The countrys infrastructure will be finished, he said with a broad, satisfied smile. I see lots of light industry in the free zones. I see the roads and hotels finished and the marinas functioning. I see Beirut as a jewel lit up at night.

But the realisation of his vision was to be thwarted by the grinding political realities of Lebanon. From 2000 onwards, Hariri was locked into an increasingly fraught and bitter struggle for control of Lebanon, one pitting him against his nemesis, Emile Lahoud, the Lebanese president and former army commander, and the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

The battle for Lebanon intensified with the onset of the Bush administrations war on terrorism and the invasion of Iraq in 2003. With pressure mounting on Syria, Bashar adopted President Bushs maxim of either you are with us or against us, in his dealings with the Lebanese. Stoked by a

Preface

ix

pernicious whispering campaign by pro-Syrian Lebanese, the regime in Damascus increasingly came to regard Hariri as a threat, a powerful Sunni who was plotting with the Americans and French against Syria. But Hariri was a compromiser, an appeaser, who only sought to place relations between Beirut and Damascus on a more equitable footing and away from one dominated by the Syrian and Lebanese intelligence agencies. He cut a deal with Hizbullah over its weapons and was willing to use his international contacts to ease the pressure on Damascus. Hariri simply wanted to deal with fellow politicians in Damascus, not a general in the Syrian military intelligence headquarters in the Lebanese town of Anjar.

Hariri wanted to be Syrias friend, but the Syrians believed he was their enemy.

The drama that unfolded was, at its heart, a Shakespearean tragedy of misunderstanding.

When I.B.Tauris and I first discussed the idea of a book on the Hariri assassination and its impact on Lebanon and beyond, Syrian troops were still on Lebanese soil and Lebanons parliamentary elections were more than a month away. I would be writing the book as the story unfolded, but it was a compelling tale to relate, one which, although rooted in the tangled complexities of Levantine politics, contained universal themes of greed, power, fear, rivalry, suspicion and murder, fundamentals of the human condition which transcend region, language and culture.

Next page