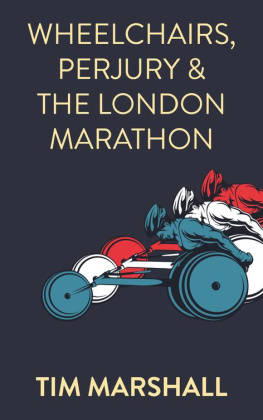

Tim Marshall - Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon

Here you can read online Tim Marshall - Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Clink Street Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon

- Author:

- Publisher:Clink Street Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The idea for writing this book came to me during a prolonged stay in the high dependency unit of the Spinal Injury Centre in Middlesbrough in early 2013. As I chatted with one of the nurses, she let slip that she had once done the London Marathon, in 1983, the first year that she was allowed to run that distance, having reached the age of 18. 1983 was also the first year that wheelchairs were let in, so we swapped memories of our experiences. The idea for a book arose from that conversation, and this is the story of how the wheelchair section came about.

Thanks to Kathy for inadvertently provoking the idea in the first place (she really didnt realise what she had unleashed!); to Mick, Mark, Denise, Gerry, Jo, Gordon, Joe, Ric, Stuart, Chas and all the others whose names I have forgotten but who were part of the early struggle; to Caroline, Jon, Libora and Liz for their comments on earlier drafts; to Liz also for her more than tacit support, which resulted in the crucial contact with the GLC; and finally to Caroline again, who, when friends have (unwisely) asked about my involvement with London, has had to suffer an abbreviated version of the whole book on innumerable occasions. Text within square brackets convey my own thoughts and feelings, often after the event. Any remaining inaccuracies and faults are of course mine. I can only plead the fallibility of memory of events over 30 years ago, and that the documentary records are rather incomplete.

In September 1972 I was climbing in the Peak District with a friend from work, on the gritstone at Birchens Edge just above the Robin Hood pub where the road from Baslow to Sheffield splits off from that to Chesterfield. Late on the Saturday afternoon I was trying to pull up a narrow crack on finger jams, but failed, and fell off, about 20 feet, landing full square on both feet and getting a compression fracture of the spine. Taken first of all to Chesterfield Royal Infirmary, two days later I was transferred to Lodge Moor Hospital in Sheffield, the regional centre for the management of spinal injuries. This was to be my home for the next eight months.

The hospital was high up on the moors at the western edge of the city, with no buildings beyond it. In the acute ward, you could hear the clip-clop of horses from the local riding school as they trotted along the roads beyond the grounds of the hospital; and, depending which way you were facing when lying in bed, you could see the helmets bobbing up and down above the dry stone walls, the sight accentuated when, as often seemed to happen that winter, the fields were covered in snow. Round to the right, and way down in a deep-cut valley, was the A57 road that came out of Sheffield, over to the Ladybower dam, and on to the Snake Pass, offering access to the high moorland of the Dark Peak. It was inviting, even if the immediate prospect of getting there was non-existent.

But the outdoors wasnt entirely out of bounds. One day I woke to a snow-covered paradise. It had snowed overnight, well over an inch, and the sky was a crystal clear blue; I decided to go out and enjoy this.. Despite the blazing sun, it was very cold as I pushed the wheelchair through an inch of snow up to the helipad at the back of the hospital, and sat there surrounded by the snow, in utter quietness, soaking in the pleasures of being outside, in the country once again. Almost everyone thought I was mad, but the ward sister who could beat me at Scrabble, and was altogether a very impressive lady knew, for me, what that experience was about; simply magical.

The physiotherapist assigned to me, Harry Charles, was a leading light in the hospital sports club strictly speaking, the Spinal Injury Sports Club so even though I was stuck in bed for the first 10 weeks, there was an early introduction to the sports side of rehabilitation. The gym, in which all the sports took place, had originally been an ordinary ward (South 2, or S 2) when the whole hospital was an isolation hospital for infectious diseases; and there was still one ward functioning as the regional infectious diseases unit. But S 2 became the gym when the Spinal Injury Unit was established there in the early 1950s.

While I was still in bed in Lodge Moor I had seen a clip on the BBCs Saturday afternoon Grandstand programme taken from the Paralympic Games held in Heidelberg. They showed a British athlete in a wheelchair doing what the programme called a slalom, pushing the wheelchair along a pre-set track, tipping the wheelchair onto its rear wheels to bounce up or down a step, ducking low like a limbo dancer to get under a low tape, and so on. My memory of this broadcast finished with the man in the wheelchair doing a back-wheel balance on the two rear wheels, and in my memory the wheelchair fell over backwards and the man fell out. The programme had introduced him as Philip Craven.

A few weeks later, still stuck in bed, I had a letter from France. I didnt know anyone in France; what on earth was this about? It turned out to be from the same Philip Craven, who at that time, he told me, was teaching wheelchair basketball, and other sports too, at a rehabilitation centre at Kerpape in southern Brittany. (The connection to him was obscure: a daughter of some friends of my parents had been at university with Philip, already in a wheelchair from a climbing accident at the age of 16. She contacted him about me, and so he wrote to me.) This was the first instance of contact with Philip that was to continue, on and off, for the next 40 years.

Once I was allowed to start getting up the gym was an obvious destination. Other than Wednesdays it was used routinely as part of the rehabilitation programme, but on Wednesday afternoons it was used by ex-patients who came up for a sort of mini sports day, when as far as possible the gym was cleared of moveable equipment to enable people to play battington (a kind of badminton but with solid rackets), table tennis, snooker and wheelchair basketball. The size of the central section of the gym, maybe 15 yards by 6, made basketball no more than 4 a side at maximum and more usually 3 especially exciting to watch.

It was Harry Charles (actually a Remedial Gymnast rather than a physiotherapist) who got me playing table tennis, along with his successor John Honey, just finishing his training in physiotherapy. Swimming was also sometimes on offer, very good for paralysed limbs, but Id never been a water sort of person, had never learned to swim, and I didnt take up the pportunity then. It was Harry, though, who first aroused my interest in wheelchair sports, and who encouraged me to go to the national championships held annually at Stoke Mandeville.

My first visit there was straight after being discharged from hospital. I had supposed that going to The Nationals, as the games were universally described, would involve a rigorous selection procedure. I had no idea what that might be, but presumably through some regional or club-based structure based on performance: were you good enough? The presumption was partly correct, in that the hospital sports club made the entry for you, including such details as sex, level of disability and which sports you were going to do; but it seemed that anyone could go, regardless of ability, provided that they were attached to an existing sports club. At that time the clubs were essentially hospital-based, and the hospitals were those with spinal injury units. So, there was my club Lodge Moor Spinal Injury Sports Club and clubs from other hospitals: Stoke Mandeville, Pinderfields (Wakefield), Southport and so on. The only exception to this that I could discover was the Scots, who came down as the Scottish Paraplegic Association, rather than from Musselburgh or Philipshill, the two hospitals in Scotland then offering specialised treatment for spinal injuries.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon»

Look at similar books to Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wheelchairs, Perjury and the London Marathon and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.