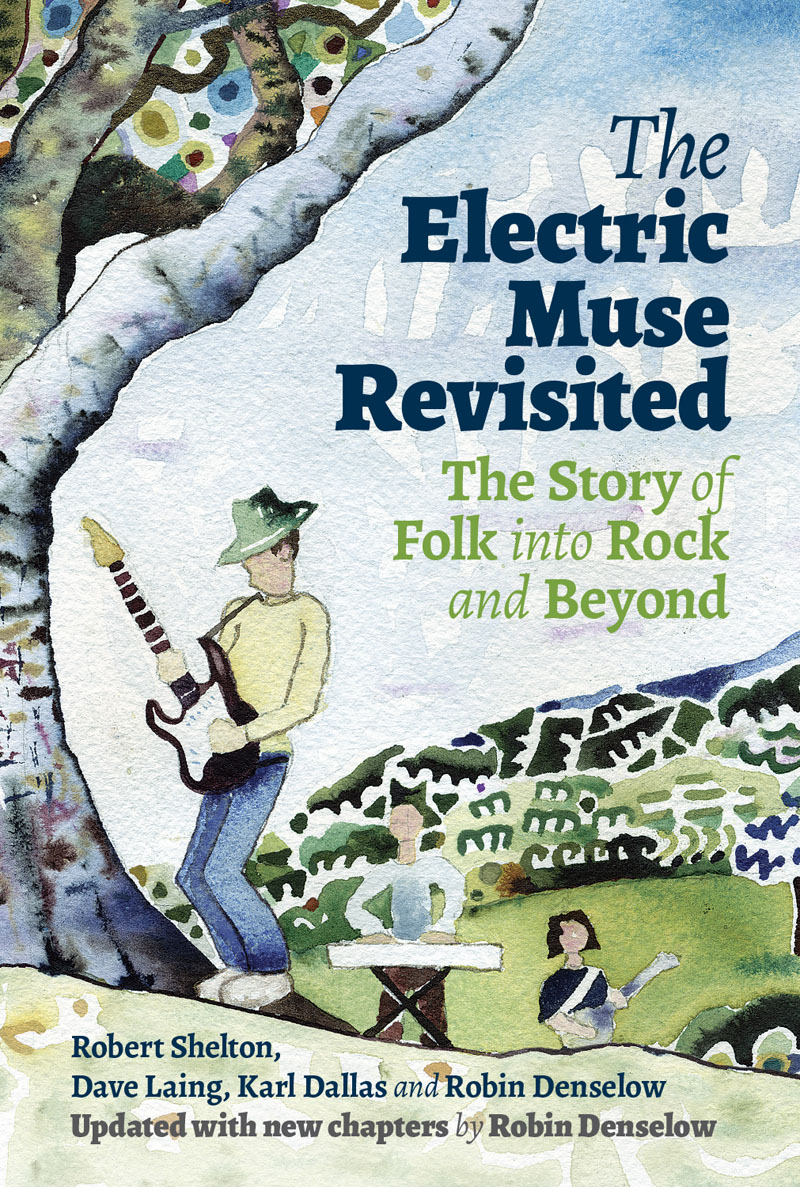

Robert Shelton - The Electric Muse Revisited

Here you can read online Robert Shelton - The Electric Muse Revisited full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Omnibus Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Electric Muse Revisited

- Author:

- Publisher:Omnibus Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Electric Muse Revisited: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Electric Muse Revisited" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Electric Muse Revisited — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Electric Muse Revisited" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

It is through the support of the folk music charity Square Roots Productions that this book has been published. For more information please visit www.folktracks.org

There have been many influences on the growth of rock music from its brash beginnings in the 1950s to its contemporary spectrum of styles and sounds. The most pervasive have been the many varieties of folk music. From the world of blues, ballads, rags and reels, rock has gained a new range of techniques, aims and ambitions. The importance of Bob Dylan in this respect is of course, well known. But even the music of so untraditional a performer as David Bowie would not have made such a tremendous impact if he too had not learned from folk music that songs can be entertaining and poetic at the same time.

The natural habitat of folk music is societies in which culture has not become industrialised, and people are not segregated into performers and listeners, the one active, the other passive. Yet one of the most marked features of British and North American culture in the last twenty years, as the mass media and the entertainment industries have expanded in scope, has been not merely the survival of folk music as a cultural force, but a major growth in its influence and in the numbers of people involved in it, whether as musicians or devotees. That fascinating paradox is one of the main themes running through this book, which traces the myriad forms taken by what has been loosely called the folk revival and examines its effects on the dominant popular music of the period, rock.

Strictly speaking, the folk revival is not so much an event as a continuous process stretching back over more than a century, and involving people as disparate as the Harvard professor, Francis James Child and the Glasgow-born Cockney traditional jazz banjoist, Lonnie Donegan. Each symbolises one of the two main aspects of the revival. Professor Child was the prototype preservationist, the compiler of a famous collection of traditional ballads which have since been used as source material by many singers. (Folk-song recordings often refer to songs by the opus number given to them by Child, as well as by the traditional title.) The preservationist attitude was based largely on the (generally accurate) belief that the oral transmission of folk music the handing down of songs from generation to generation through their memorisation rather than through written records had virtually broken down by the last part of the nineteenth century.

Such tender concern for the integrity of folk music has never been a feature of the activity of the popularisers of the songs, like Lonnie Donegan, whose recording of Leadbellys Rock Island Line sparked off the skiffle movement of the late 1950s in Britain. Inspired by Donegan thousands of young people formed themselves into skiffle groups, and learned his eclectic repertoire of American folk songs from both black and white sources, plus a smattering of numbers deriving from pre-war jazz. What drew them to skiffle was its rhythmic intensity compared with the moribund popular music of the day, not its roots in folk traditions unsullied by commercialism. The point was proved when rocknroll appeared on the horizon with its even stronger rhythms, and the skifflers exchanged their acoustic guitars for electric ones. Nevertheless, through skiffle and rocknroll, elements of certain kinds of folk music entered the mainstream of commercialised entertainment and had a significant effect on it. A similar but more far-reaching process occurred in the early 1960s in America when the younger singers of the mushrooming folk-song movement merged their approach with that of the new British pop sound to produce what came to be known as folk-rock, a music which at its best could fuse the pungency of folk poetry with the power of rock rhythms.

But for all its faults, the preservationist attitude has provided an essential underpinning for the flourishing folk music scene of today, and indeed for the maturity of an important segment of contemporary rock music. Without Francis Child, no Bob Dylan or Steeleye Span. And it is easy to underestimate the courage of the early song collectors. In the face of apathy or ridicule from their peers, city intellectuals travelled through alien territory whether it was the countryside of Somerset or Mississippi notebook or tape-recorder in hand, persuading the folk to sing and play for them. Even if they accompanied their findings with laments that the end of the tradition was at hand, when often it proved to be far more robust, the results of their work are the foundation stones upon which the whole edifice of later folk-song movements was built.

The work of the collectors had, however, certain important but unintended effects. For, while they felt themselves to be simply making an objective study of folk music, the collectors played a part in shaping the picture which emerged. This often happened in Britain because the researchers brought to the culture of a lower-class, peasant society the values of the educated middle class. Victorian prudery, for example, caused Cecil Sharp and other collectors to tidy up songs containing explicitly sexual imagery. The original manuscript versions of some folk songs that later became school-room standards were not published until 1958, when James Reeves presented them in his valuable study, The Idiom of the People.

There was, in addition, the problem of the transcription of the music itself. The British collectors, steeped in the art music of their period, were accustomed to thinking of music in written terms, conforming to the scales and tempi of the classical forms. But folk music of any kind is produced in a very different way. In an interview, Louis Armstrong once spoke of blues and jazz being made by the kind of man who doesnt know anything about (formal) music who is just plain ignorant, but has a great deal of feeling hes got to express in some way, and has got to find that way out of himself.

The arrival of machines capable of recording the sound of folk song meant that the distortions which inevitably followed from the translation of the music into classical notation could be avoided. It was now possible to capture those aspects of vocal tone and inflection for which notation had no symbols. Then, of course, these field recordings were also a kind of interference (if a less damaging one) with the operation of the tradition since they tended to enshrine one particular variant of a song for posterity, in contrast to the process of oral transmission which involved the re-moulding and modification of music as it was handed on from one singer to another.

Perhaps the most crucial modification of the tradition produced by the activities of the preservationists occurred when it came to the use of the collected material in performance. The songs were transplanted by the singers who learned them following their publication by collectors into contexts very different from those in which they originated. Some, though, were closer to the spirit of the original than others. While the British collectors from the beginning were imbued with the feeling of the drawing room and the music teacher, many of the pioneers discussed in Robert Sheltons chapter on the folk revival in the United States were of a more radical temper. Like the poet Walt Whitman, men such as Charles Seeger and Carl Sandburg felt that the cultural heart of their country lay with the people.

From there it was a short step to the liaison of political radicalism with folk song, which has always been a far more important aspect of folk revivalism in America than in Britain, though, as Karl Dallas points out in his chapter, there was a political impetus behind certain aspects of the revival in England. On the other side of the Atlantic though, songs were created from within popular movements, and a clear line can be traced from the martyred union organiser Joe Hill through Woody Guthries Dust Bowl Ballads to contemporary performers like Pete Seeger and Joan Baez.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Electric Muse Revisited»

Look at similar books to The Electric Muse Revisited. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Electric Muse Revisited and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.