ALSO BY MARK HARRIS

Five Came Back

Pictures at a Revolution

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2021 by Mark Harris

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Quotation from Merrily We Roll Along, book by George Furth, music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim: The Blob, Rilting Music, Inc., 1981, 1987. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Harris, Mark, 1963 author.

Title: Mike Nichols: a life / Mark Harris.

Description: First edition. | New York: Penguin Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016901 (print) | LCCN 2020016902 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399562242 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780399562259 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Nichols, Mike. | Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.N54 H37 2021 (print) | LCC PN1998.3.N54 (ebook) | DDC 791.4302/33092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016901

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016902

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

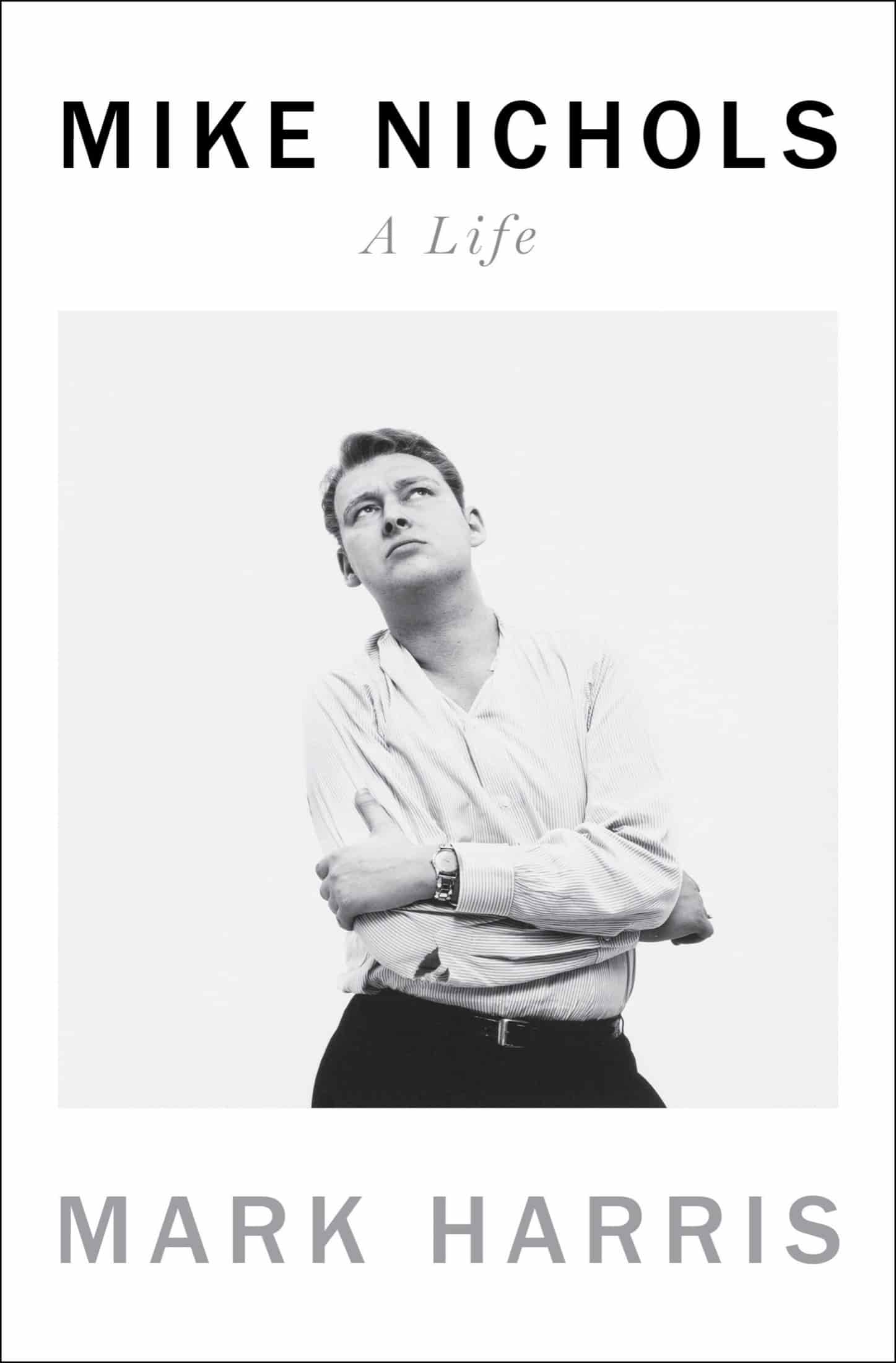

Cover design: Darren Haggar

Cover photograph: Mike Nichols, New York, February 4, 1960. Photograph by Richard Avedon. The Richard Avedon Foundation.

pid_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For Tony

You dont know whats going to happen. Big things look like little things. Little things dont have big signs on them that say This is a Big Thing. They look like everything else. Disaster can reorder our lives in wonderful ways, and you just go on to the next thing. I passionately believe that in art, and certainly in the theater, there are only two questions... The first question is: What is this, really, when it happens in life? Not what is the accepted convention... but what is it really like? And the other question we really have to ask is, What happens next?

Mike Nichols

CONTENTS

PART ONE

What It Was Really Like

One

STARTING FROM ZERO

19311944

In the origin story that Mike Nichols liked to tell, he was born at the age of seven. The first image of himself he chose to conjure for people was that of a boy on a boat, holding his younger brothers hand, traveling from Germany to America. They were unaccompanied on that six-day crossing in 1939, their ailing mother still bedbound in Berlin. Their father was already in New York. His two small sons had not seen him for almost a year.

Nichols was not yet real even to himself. His name was Michael Igor Peschkowsky, or perhaps it wasnt. Decades later, his brother, Robert, looking into his familys history, told him that according to the ships manifest and the petition for naturalization that was later filed by his father, his name was actually Igor Michael Peschkowsky. Igor. A horror-movie name. Nichols looked at him impassively. Maybe, he said. Maybe it was. It didnt matter. Whatever his name when he boarded ship, it was gone by the time he got to New York.

Nichols turned the transatlantic crossing into a storyhis first self-revelation-as-anecdote, an approach that he would eventually refine into a shield and a disguise, but also into a style of directing, a means of conveying an idea or a feeling or a circumstance to an actor that he deployed with precision and finesse over a five-decade career in movies and theater. He first tried it out on journalists in his twenties, when suddenly everyone wanted to know who Mike Nichols was and where on earth he had come from. The story he told, droll and wry, with a slight undertow of despair, was that at seven he was packed onto the boat knowing only two sentences in what would become his new language: I do not speak English and Please do not kiss me. In some tellings, he spoke no English at all and instead wore those two warnings on a penciled sign that was pinned to his clothes before boarding. It was this picturethe New Yorker cartoon version of his early life, with a punch line that hinted at both utter solitude and defiant standoffishnessthat Nichols used to explain his personality to others, and to himself: a portrait of the artist as the Little Prince, alone on his planet and at home nowhere.

If the boy who had existed for seven years before that journey usually went undiscussed in interviews, it was in part because Nicholss life before America was so hazy to him that he could retrieve little of it until adulthood. His childhood in Berlinhis years as either Michael or Igorbarely existed in his memory. As a youngster, he attended the Private Jdische Waldschule Kaliski, an elementary school that, during Hitlers rise, became a Jews-only institution. Nicholss father, a doctor named Pavel Peschkowsky, was a Russian Jew, albeit so secular that he didnt even believe in circumcision. His mother, Brigitte Landauer, was a German Jew, wholly invested in and proud of her national heritage and also indifferent to her religion. Within their cultural circle, Paul and Brigitte were not atypicalas Lotte Kaliski, who founded the school Nichols attended, put it, We all had to learn to become Jewish. Most of us came from very assimilated families and so did the children. But we understood that in order to give children a more positive attitude, they had to know something about their background.

Whatever that education was to be, Michaelor, as Elaine May later teasingly called him, little Igorwas not in the school long enough to absorb it. His memories of the Kaliski school were few, and mostly miserable. He recalled a group of German children in black shirts stealing his bicycle. And, more vividly, he could picture with awful clarity a scene with my gym teacher and my mother, and realizing they were lovers. She was a beautiful woman, and I remember her quarreling with him, and he ripped a necklace off her and threw it out a window, and she went running after it. As an adult, Nichols spoke as if that moment were still raw, admitting, I suppose Ive spent a large part of my life trying to sort that out. But at other times, he pushed the door shut. A Jew in Nazi Germany, parents always fighting, he would say, as detached as if he were musing about a stranger. Arent all childhoods bad?

His ancestrythe family legend, as he called itwas dramatic, filled with art and politics, wealth, loss, privation, and bloodshed. When he left Berlin as a little boy, he knew hardly any of it. His mother and his aunt had given him and Robert the good parthe was a cousin of Albert Einstein, no less, and thus had a famous relative already in America, a story he became so certain was prideful apocrypha that he was astonished when it turned out to be true. But they left out virtually everything else. He knew that his father was now a two-time emigrant; as a young anti-Bolshevik supporter of Alexander Kerensky, he had fled Russia, crossing the Gobi Desert into Manchuria and eventually resettling in Germany. But not until Nichols was almost eighty did he learn that a fortune in gold had helped Pavel Peschkowsky start his new life. Jews with goldmines! he marveled when, during a guest appearance on a TV genealogy show, he first heard the truth. One of his great-grandfathers, Grigory Distler, had taken possession of what was thought to be a depleted mine on Sakhalin Island and found an immense undiscovered trove of gold, enough to give his daughter Anna and her sonNicholss fatherseventy-five bars. The inheritance enabled their passage out of Russia and allowed Peschkowsky to set up a successful medical practice in Berlin. I always had this picture of my father somehow working his way up, Nichols said. They were rich! Who knew? I wish to God I had gotten to know my father better, because I had it all wrong.