Barker - The Schneider Trophy Races

Here you can read online Barker - The Schneider Trophy Races full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Silvertail Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Schneider Trophy Races

- Author:

- Publisher:Silvertail Books

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Schneider Trophy Races: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Schneider Trophy Races" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Schneider Trophy Races — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Schneider Trophy Races" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

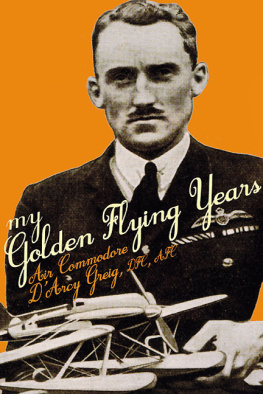

Ralph Barker

Circuitmaps, incorporatedinthetextatappropriatepoints, areprovidedforeachrace.

RACE

1 TheVisionofJacquesSchneider

The man who began it all, Jacques Schneider, was a visionary who saw in the seaplane mans brightest hope for spanning the oceans and bringing the corners of the earth closer together. Born near Paris on 25th January 1879, he was the son of the owner of the Schneider armaments works at Le Creust, and he was trained as a mining engineer; but when aviation fever spread through France after the flying of Wilbur Wright at Le Mans in 1908 his mind turned in the reverse direction, and he became passionately interested in aviation. His fascination with the subject was broad: after joining the Aero Club of France in 1910 he gained his pilots brevet in March 1911 and qualified as a pilot of free balloons a fortnight later, and in 1913 he broke the French altitude record in his balloon Icare with a height of 10,081 metres. These successes were achieved despite multiple arm fractures suffered while hydro-planing at Monte Carlo in 1910, which left him handicapped for life.

But for this accident Schneider might have gained greater fame as an aviator; but with his active career restricted he turned more and more to the organising of aviation events and competitions, and he was soon struck by the neglect of the seaplane as opposed to the landplane form. His concept of a special contest for seaplanes thus combined a vision of maritime aviation with a passion for speed; at the banquet following the fourth annual James Gordon Bennett race for landplanes on 5th December 1912 he presented the trophy which bears his name.

The trophy is a vessel of silver and bronze, mounted on a base of dark-veined marble, in which a nude winged figure representing speed is shown kissing a zephyr recumbent on a breaking wave. Into the breaking wave the heads of two other zephyrs are worked, also the head of Neptune, god of the sea. The symbolismspeed in the elements of sea and airis clear. The trophy stands today in the Science Museum, London, under the winning aircraft, but Schneider did not live to see it settle in any permanent home; he died at Beaulieu-sur-Mer, near Nice, not far from the Monaco course where the first Schneider race was run, on 1st May 1928, at the age of 49. He died in reduced circumstances and in relative obscurity, at a time when vast sums were being spent in quest of the trophy he presented.

Schneiders vision of a world traversed by seaplanes and flying-boats must have seemed, in the 1920s and 1930s, very likely to be fulfilled; long ocean cruises were accomplished in these years by most of the major air powers, led by America, Italy and Britain, and the first trans-ocean commercial routes were opened up by flying-boats. But by the end of the Second World War, concrete runways of suitable length, conveniently situated, were available in most parts of the world, and the efficiency and endurance of landplanes had greatly increased. When global air transport eventually became available to all, it was the landplane that provided it. And in the field of air defence, the seaplane had long since been eclipsed by the landplane. Nevertheless the contest for the Schneider Trophy, spanning as it did 18 years in all, from 1913 to 1931, had a far wider influence on aviation than mere advancement of the seaplane form, proving to be the strongest of all peacetime incentives to aviation progress. Especially was this true in the development of power and reliability in aircraft engines and in clean aircraft design.

2 TheFirstSeaplanes

It was more than six years after the Wright Brothers made their famous flight at Kitty Hawk in December 1903 before anyone was successful in using water as a runway for powered flight. The man who succeeded was a Frenchman named Henri Fabre. Born at Marseilles in 1882, and still alive today, he studied the work of the French landplane pioneers before building his first hydro-aeroplane in 1909. On 28th March 1910, with no previous experience of flying, not even as a passenger, he made his first successful flight. Although lack of finance prevented him from continuing his experiments he must rank alongside the great American Glenn Curtiss as the progenitor of the seaplane.

Glenn Curtiss, winner of the first of all international air racesthe James Gordon Bennett Cupat Rheims in 1909, at a speed of 47 m.p.h., also began his hydro-aeroplane experiments in 1910, but it was not until January 1911 that he made his first successful flights. He progressed so rapidly, however, that by 1912 he was supplying a primitive form of flying-boat to the United States Navy. In later years his racing biplanes were to dominate the Schneider contest and very nearly win the trophy outright for America.

The first flight of a seaplane in Britain (it was a modified Avro landplane) was made at Barrow in November 1911; like Henri Fabre, the pilot, Commander Oliver Schwann, had never flown before. In the same month the Admiralty gave permission for four naval officers to learn to fly, and a naval arm of the Royal Flying Corps was formed in 1912. Horace and Eustace Short, already established at Rochester as boatbuilders, branched out into aviation and soon earned orders from the Admiralty, and a young man named Sopwith was building an amphibian at Kingston-on-Thamesa pusher biplane bolted on to a hull constructed by boatbuilder Sammy Saunders at Cowes. (The requirements of strength of construction combined with lightness made the boatbuilders the natural allies of the plane-makers.) France, Germany and Italy were building on similar lines.

Yet by far the majority of the entries at the early hydro-aeroplane meetings in Europe (they were not called seaplanes until Winston Churchill dubbed them such in 1913, after he became First Lord of the Admiralty) were hastily converted landplanes, and their instability and general unsuitability for water-work betrayed their origin. Pilots flew them gingerly, not daring to bank steeply because of the cumbersome floats, and spills of all kinds were frequent. The design of floats was primitive, and little attention was paid to the technique of hydroplaning. The German hydro-aeroplane meeting at Heilingendamm, said a report of the period, was in many respects a distinct farce, as it was some time before any of the competitors could rise from the water at all.

Two Curtiss biplane flying-boats took part in the first hydroaeroplane meeting at Monaco in 1912, but although they took third and fourth places in the Grand Prix they were beaten for speed by the box-kite Farman biplanes mounted on floats. It did not seem likely that the flying-boat, with its greater weight and increased head resistance, would be able to compete for speed with the twin-float seaplane; but what the flying-boat lacked in speed and manoeuvrability it gained in robustness, and as the rules of the Schneider contest called for various tests of seaworthinessdesigned to eliminate the freak machine constructed purely for speedflying-boats played an important part in the races for some years.

3 TheFlyingFlirt

The full title of the Schneider contest was La Coupe dAviation Maritime Jacques Schneiderthe Schneider Cup to the British and Americans and the Coppa Schneider to the Italians; but it was not, of course, a cup at all. Yet the nations in pursuit of the sculptured trophy all recognised the sensuality of its design and the aggressive femininity of the winged figure representing speed, so that by the early 1920s, when France, Great Britain and Italy had all in turn possessed her, she had earned the soubriquet of the flying flirt. Yet she was not by nature promiscuous, her lifespan being divided into four great loves. Her first love, as might be expected, was France, the boy next door. Then, after seeming likely to make her permanent home in Italy, she was swept off her feet by the Americans. Carried back three years later in brief triumph to Italy, she finally settled in England.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Schneider Trophy Races»

Look at similar books to The Schneider Trophy Races. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Schneider Trophy Races and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.