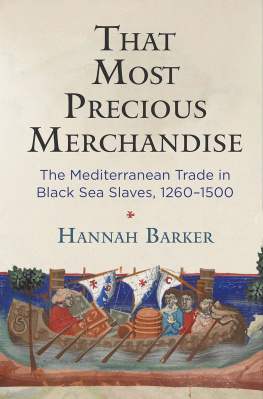

Barker - That Most Precious Merchandise

Here you can read online Barker - That Most Precious Merchandise full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc., genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

That Most Precious Merchandise: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "That Most Precious Merchandise" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

That Most Precious Merchandise — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "That Most Precious Merchandise" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

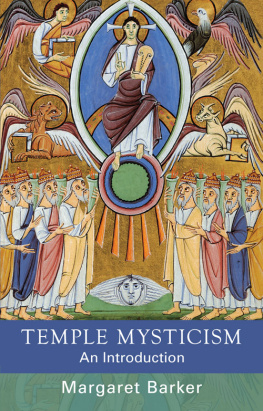

That Most Precious Merchandise

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

THAT MOST PRECIOUS MERCHANDISE

The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 12601500

Hannah Barker

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barker, Hannah, author.

Title: That most precious merchandise: the Mediterranean trade in Black Sea slaves, 12601500 / Hannah Barker.

Other titles: Middle Ages series.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, [2019] | Series: The Middle Ages series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006688 | ISBN 9780812251548 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Slave tradeMediterranean RegionHistoryTo 1500. | SlaveryMediterranean RegionHistoryTo 1500.

Classification: LCC HT983.B37 2019 | DDC 306.3/6209822dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006688

Contents

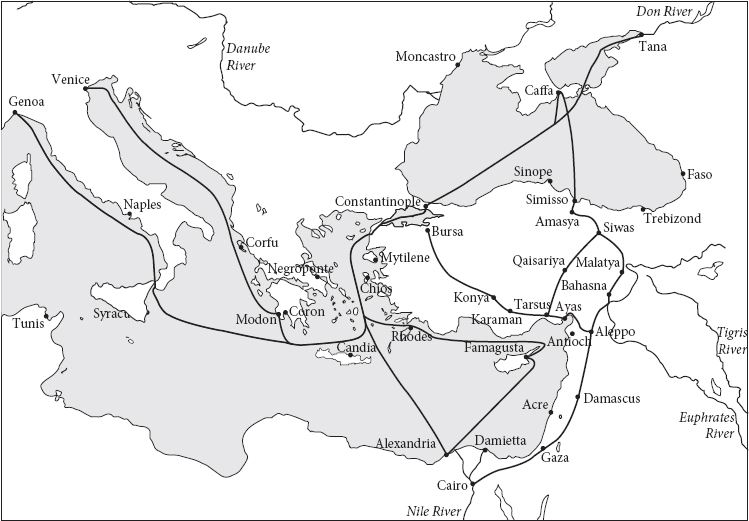

Map 1. The Black Sea. Map created by Hannah Barker using data from naturalearthdata.com.

Map 2. Slave Trade Routes. Map created by Hannah Barker using a template from Daniel Dalet (d-maps.com).

Introduction

On September 19, 1363, a ten-year-old Tatar boy named Jaqmaq was sold as a slave in the Black Sea port of Tana. His first owner had probably been a Christian, as he had already been baptized with the name Antonio. His second owner was a local Muslim named Aqbugh, the son of Shams al-Dn. Aqbugh sold Jaqmaq/Antonio to his third owner, Niccol Baxeio of the parish of St. Patermanus in Venice, for 400 aspers. Niccol also bought a fifteen-year-old Tatar girl from Aqbugh and a twelve-year-old Tatar boy from another local man. All three children were to be delivered to different people in Venice. Jaqmaq/Antonio was destined for Gabriel Teuri of the parish of St. Severus, who would be his fourth owner.

About twenty years later, another boy named Jaqmaq, this time a Circassian, was also sold as a slave in the Black Sea. He was purchased by a merchant named Kazlak, who brought him to Egypt. There Kazlak sold him to a military commander, the amir Al ibn Inl, who trained him as a mamluk, a military slave. Once his education was complete, Jaqmaq accompanied Als mother on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Upon his return, he discovered that his older brother was also serving as a mamluk in another household, that of the sultan of Egypt. When the sultan found out, he took Jaqmaq away from Al ibn Inl and added him to the royal household, reuniting the brothers. After some additional training, the sultan freed Jaqmaq and made him a page at court. Over the course of several decades, Jaqmaq rose through the ranks in the court and army. In 1438, he himself became sultan and enjoyed a long reign until 1453. During that period, he purchased thousands of slaves to staf his household and serve as mamluks in his army. His successor, al-Manr Uthmn, was his son by a Turkish slave woman named Zahr.

The life of the first Jaqmaq, the Tatar boy sold to Venetians, is documented only through a single entry in the register of the notary who drew up the contract for his sale. There are coins minted in his name, and the school (madrasa) that he endowed still stands in Cairo today. Yet these sources reveal more about his political career than his early life as a slave. What binds the two Jaqmaqs together, despite their radically different fates in both life and the historical record, is their involuntary participation in the Mediterranean trade in Black Sea slaves.

The history of the Black Sea as a source of Mediterranean slaves stretches from ancient Greek colonies to human trafficking networks in the present day. During the medieval period, the trade in Black Sea slaves peaked between the mid-thirteenth and mid-fifteenth centuries. More precisely, it was in the 1260s that the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Paleologus granted commercial privileges in the Black Sea to the rulers of Genoa, Venice, and the Mamluk kingdom of Egypt and Greater Syria (bild al-Shm). On the basis of those privileges, Mediterranean merchants settled in the Black Sea and exported various goods, including slaves. Slave exports continued until 1475, when Ottoman forces conquered Caffa, Genoas chief colony on the Crimean Peninsula. Although the Black Sea slave trade did not end in 1475, it was reorganized to serve Ottoman rather than Italian or Mamluk needs.

Even at its height during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the Black Sea slave trade was never the sole source of Mediterranean slaves. Genoese and Venetian merchants bought the captives taken in conflicts throughout the Mediterranean region. The Genoese bought slaves from ongoing wars between Christian and Muslim kingdoms in Iberia, and they also enslaved Sardinians caught up Genoas war with Pisa. The Venetians bought slaves from pirates and raiders in the Balkans and the Aegean Sea. Both Genoa and Venice enslaved captives taken from North Africa and the Ottomans. When allowed to do so, they also purchased African slaves in Alexandria, Tunis, and other North African ports. However, the greatest demand for slaves in the medieval Mediterranean was concentrated not in Italy but in Cairo, home of the Mamluk sultan and his amirs, the commanders of his army. The Mamluks preferred Black Sea slaves for military service, but they also imported large numbers of African slaves for domestic service as well as slaves from the Balkans, the Aegean, Central Asia, and the Indian Ocean when they were available. Yet within this diverse population of slaves, those from the Black Sea were the single largest group. The trade in Black Sea slaves provided merchants with profit and prestige; states with military recruits, tax revenue, and diplomatic influence; and households with the service of enslaved women and men.

The trade system that carried slaves from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean is the subject of this book. Genoa, Venice, and the Mamluk sultanate, the three most significant importers of Black Sea slaves, have never been studied together. The main obstacle has been language: an integrated study of the Mediterranean trade in Black Sea slaves must draw on sources in both Latin and These included the ideas that slavery was legal and socially acceptable, that slave status was based on religious difference, that religious difference could be at least partially articulated through linguistic and racial categories, and that slavery was a universal threat affecting all free people. It also included practices related to slave conversion, the inspection process and contractual language for buying and selling slaves, the use of slaves as social and financial assets, a strong preference for slave women over men, the widespread use of slave women for domestic and sexual service in urban households, and the status of children born to slave women and free men.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «That Most Precious Merchandise»

Look at similar books to That Most Precious Merchandise. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book That Most Precious Merchandise and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.