Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

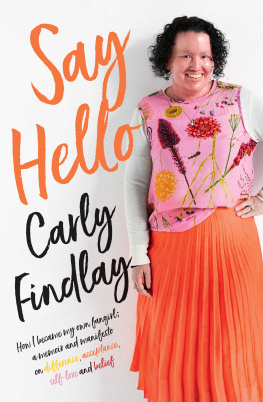

Introduction and selection Carly Findlay 2021

Carly Findlay asserts her moral rights in the collection.

Individual stories retained by the authors, who assert their rights to be known as the author of their work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760641436 (paperback)

9781743821374 (ebook)

Cover art by Wendy Duncan

Cover and typesetting by Akiko Chan

Text design by Tristan Main

Introduction

Carly Findlay OAM

Like some of the other contributors to this anthology, I didnt grow up disabled. Even though I have a severe lifelong skin condition, I rejected the term disabled because I thought it had negative connotations and I didnt see how it related to me. The only time I saw disabled people in the media was when they competed in the Paralympics, or when a tabloid TV show was painting their life as a tragedy. And I didnt see anyone like me. I thought disability looked a certain way. And I didnt fit that.

Because I didnt identify as disabled, I wasnt able to advocate for the support I needed in school, nor recognise or speak up against discrimination towards other disabled people. In hindsight, its clear that I had internalised ableism. By insisting I wasnt disabled, I was perpetuating the othering. And I lacked a sense of pride and community.

It wasnt until I was in my mid-twenties, when I mentored young people with chronic illness, that I realised how much we had in common serious lifelong conditions that required many specialists at the hospital, extended absences from school and work, and encountering attitudinal barriers from ignorance or discrimination. These young people allowed me to work through that internalised ableism and showed me that I could embrace the term disabled.

I began writing publicly about life with ichthyosis, which led to work in the mainstream media and presenting on a disability-led TV show called No Limits. I got to know more chronically ill and disabled people and came to understand the social model of disability. This model acknowledges the physical, attitudinal, communication and social barriers faced by people with impairments. It challenges these obstacles by arguing that society should accommodate impairment as an expected aspect of human diversity. I felt safe to embrace the label of disabled because of the writing and friendship of other disabled people. And this meant I could finally advocate for myself and for others.

I now identify as a proud disabled woman, not wanting to hide my disability and chronic illness. And I want to help be the change in the media, so that young disabled people can see themselves and whats possible for them.

I hope that this book can be a friend to people who need it, because its a friend I needed when I was younger.

This book will change history. Its the first of its kind in Australia. And I hope it wont be the last. Publishers both literary and news need to commit to publishing work by disabled people. We deserve better representation in literature.

From 2010 to 2014, Stella Young edited ABC Ramp Up. It was a place for disabled people to write about our own experiences, advocate for policy change and celebrate disability pride. The government defunded it in 2014, and there hasnt been a dedicated place for Australian disability writing online since. While Growing Up Disabled in Australia has a finite number of stories and will never replace Ramp Up, I am glad to have helped provide a writing space for disabled people to tell their stories. I am forever thankful for Stellas work, and I read and reference her writing regularly.

We had over 360 submissions to Growing Up Disabled in Australia. It was such an honour reading through the submissions one of the best jobs Ive ever had. The quality of writing is extraordinary, and there is a definite hunger from disabled people to tell their stories (and to read the stories of others).

Choosing the contributors was a hard task I wish we could have included many more. Im proud of everyone who submitted and encourage those who didnt get into this anthology to keep writing and find other opportunities for their work.

This anthology shows the diversity of disability not just in terms of impairments, but also experiences. I took an intersectional approach when selecting the work. The people in this book are disabled, chronically ill, mentally ill and neurodiverse, and inhabit the city, regional and rural regions and Aboriginal communities. They span generations some are elders and some are still growing up and genders, cultures and sexualities. Not everyone in the book sees disability as part of their identity, but some are waving the pride flag loudly; both responses are valid. Some people have chosen to use a pseudonym, such is the stigma or fear of speaking out about disability.

I hope this book creates a sense of identity, pride and belonging to a community for the contributors and for readers.

I cant wait to see these writers fly.

A note on the social model of disability

Growing Up Disabled in Australia is based on the social model of disability. People with Disability Australia describes this as follows: The social model sees disability is the result of the interaction between people living with impairments and an environment filled with physical, attitudinal, communication and social barriers. It therefore carries the implication that the physical, attitudinal, communication and social environment must change to enable people living with impairments to participate in society on an equal basis with others.

A social model perspective does not deny the reality of impairment nor its impact on the individual. However, it does challenge the physical, attitudinal, communication and social environment to accommodate impairment an expected incident of human diversity.

Question Marks and a Theory of Vision

Andy Jackson

I didnt grow up disabled. My body and its place in the world seemed normal to me. Why wouldnt it?

I grew up in Bendigo, a goldfields city in central Victoria, a city small enough to safely ride around on a bicycle unsupervised, but large enough to have a shopping mall and the first Myer in Australia. We lived in a relatively new suburb, with clusters of mid-century quarter-acre homes surrounded by former quarries that had become vacant lots. In the imaginations of the children who lived there, they were far from vacant. As soon as I could ride a bike, I was out there on those hillocks and dunes, daydreaming places where I could escape myself and belong at the same time.

My father was a salesman, tall and unusually shaped, with a prosthetic leg. I only learnt this latter detail later on. Mum was stoic and uninterested in focusing on the negatives. In photographs from the time, Dad wore white business shirts and had slicked-down hair. My brother and I clambered around him, his posture suggesting love, albeit undemonstrative, and mild disinterest. To remember him, I only have these photos, because when I was two, before my brain had the chance to develop the capacity for long-term memory, he had some kind of cardiac event, was rushed to hospital and died.

Next page