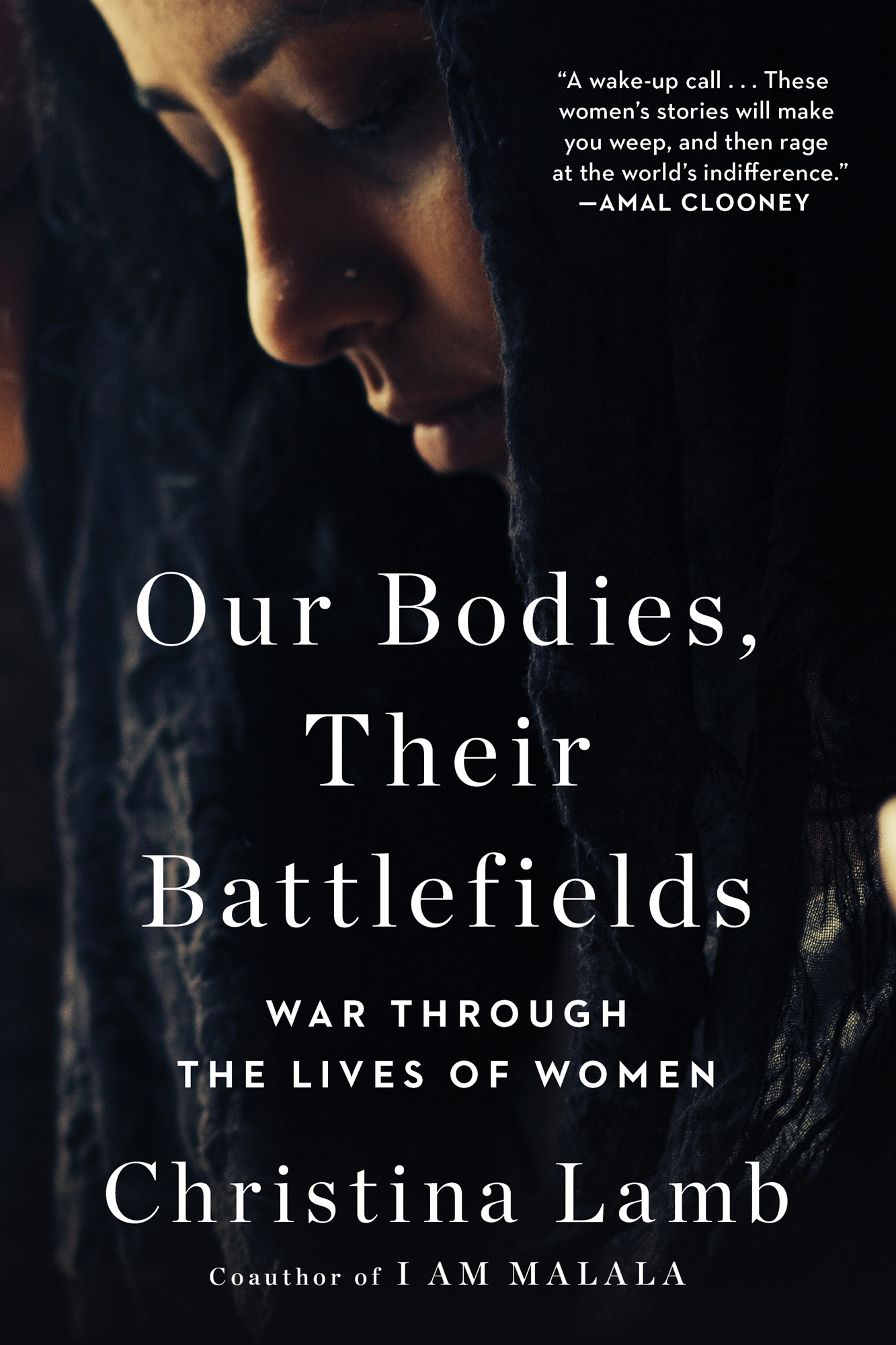

Christina Lamb - Our Bodies, Their Battlefields

Here you can read online Christina Lamb - Our Bodies, Their Battlefields full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Scribner, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Our Bodies, Their Battlefields

- Author:

- Publisher:Scribner

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Our Bodies, Their Battlefields: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Our Bodies, Their Battlefields" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Our Bodies, Their Battlefields — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Our Bodies, Their Battlefields" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

We have given our most precious thing and have died inside many times but you wont find our names engraved on any monument or war memorial.

Aisha, survivor of rape in the 1971 Bangladesh war

They put the names in the bowl and began to draw them out. Ten names, ten girls. The girls quivered like kittens caught under a dripping tap. For them this was no lucky dip. The men pulling out the slips of paper were fighters from Islamic State and each would take a girl as a slave.

Naima stared at her hands, blood pounding in her ears. The girl next to her was younger than her, about fourteen, and mewling with fear, but when Naima tried to hold her hand, one of the men whipped off his belt and lashed them apart.

That man was older and larger than the others, around sixty, she guessed, with a belly cascading over his trousers and a vicious curl to his lips. By then she had been nine months in ISIS captivity. She knew none of them were kind but she prayed that one didnt pick her name.

Naima. The man who read out her name was Abu Danoon. He looked younger, almost like her brother, the hair on his chin still fluff; maybe he would have less cruelty in his heart.

The draw continued. The fat man picked out the young girl next to her. But then he said something to the others in Arabic, pulled out two crisp hundred-dollar bills, and slapped them on the table. Abu Danoon shrugged, pocketed the money, and handed over his slip of paper.

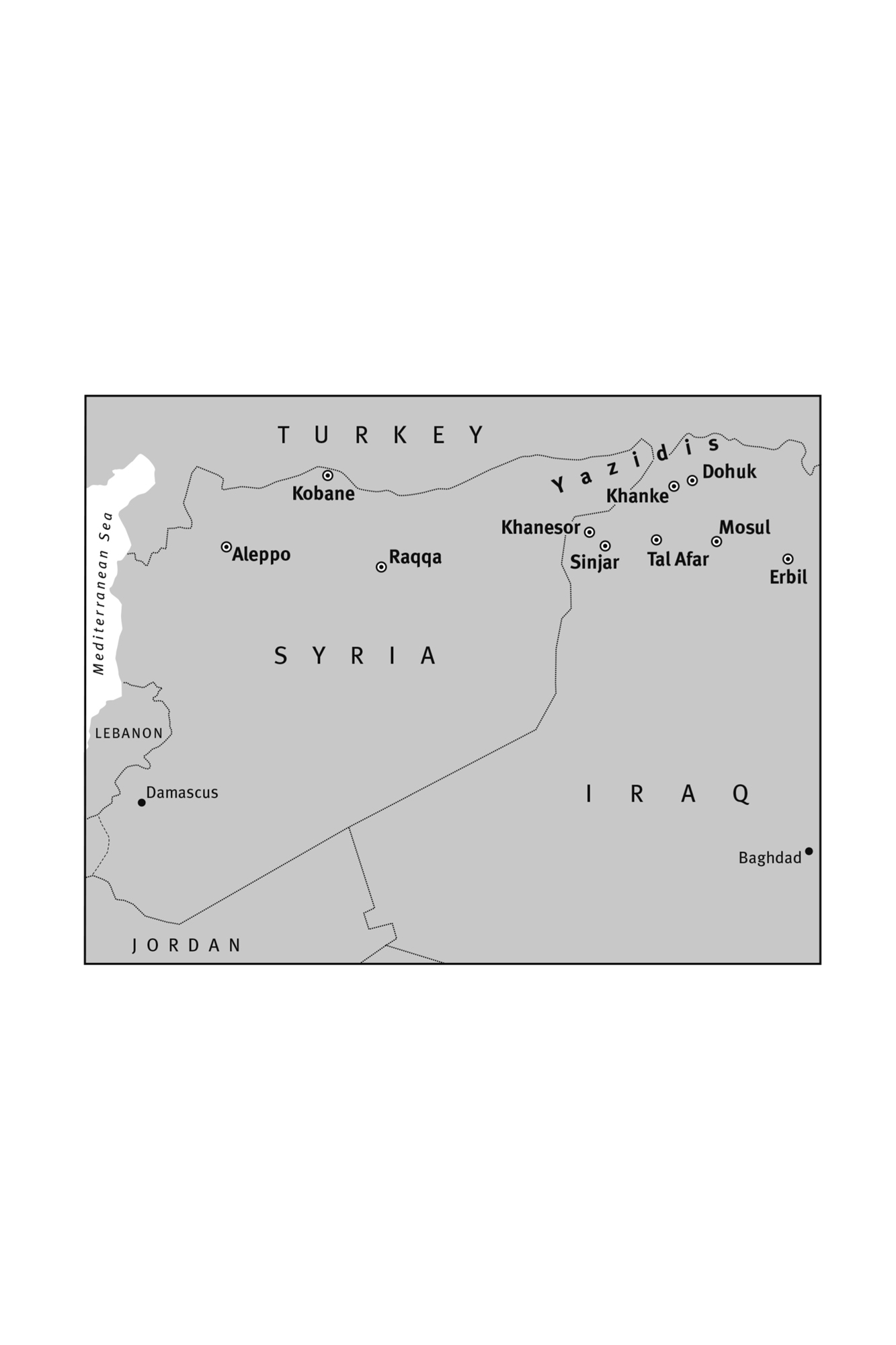

Minutes later the fat man was shoving her into his black Land Cruiser and driving through the streets of Mosul, a city she had once dreamed of visiting but which was now the capital of these monsters who had swept into her homeland and abducted her and six of her brothers and sisters, among thousands of others.

She stared through the tinted windows. An old man sitting on a cart was whipping a donkey to jerk it forward, and people were out shopping, though the only women in the streets were in black hijab. It was strange to see everyday life still going on for other people, almost like watching a movie.

Her captor was an Iraqi called Abdul Hasib and he was a mullah. The religious ones were the worst.

He did everything to me, she later recounted. Hitting, sex, pulling my hair, sex, everything. I was refusing, so he forced me and hit me. He said, You are my sabayamy slave.

After that I just lay there and tried to float my mind above my body as if it was happening to someone else so he couldnt steal all of me.

He had two wives and a daughter but they did nothing to help me. In between pleasing him I would have to do all the housework. Once I was washing dishes and one of the wives came and made me take a tabletsome kind of Viagra. They also gave me contraceptives.

Her only respite came every ten days when the mullah went to Syria to visit the other part of their caliphate.

After a month or so, Abdul Hasib sold her for $4,500 to another Iraqi called Abu Ahla, a healthy profit. Abu Ahla ran a cement factory and had two wives and nine children. Two of his sons were fighters with ISIS. It was the same thing, forcing me to have sex but then he took me to the house of his friend Abu Suleiman, and sold me for $8,000. Abu Suleiman sold me to Abu Daud, who kept me for a week; then he sold me to Abu Faisal, who was a bomb maker in Mosul. He kept me for twenty days of raping then sold me to Abu Badr.

In the end she was sold to twelve different men. She lists them one by one, their noms de guerre and real names, even their childrens names, all of which she committed to memory, for she was determined they would pay.

To be sold like that from one to another as if we were goats was the worst, she said. I tried to kill myself, to throw myself out of a car. Another time I found some tablets and took the lot. But still I woke up. I felt even death didnt want me.

I am writing a book about rape in war. Its the cheapest weapon known to man. It devastates families and empties villages. It turns young girls into outcasts who wish their lives over when they are hardly begun. It begets children who are daily reminders to their mothers of their ordeal and are often rejected by their community as bad blood. And its almost always ignored in the history books.

Every time I think I have heard the worst I can hear, I meet someone like Naima. In jeans and a checked shirt with black sneakers, her hazel-brown hair drawn back in a ponytail from a pale scrubbed face, she looked like a teenager, though she was twenty-two and had just turned eighteen when she was captured. We sat on cushions in her neatly swept tent in Khanke Camp near the northern Iraqi city of Dohuk, one of row upon row of white tents that had become a home of sorts to thousands of Yazidis. We talked for hours. Once shed started, she did not want to stop. And though sometimes she laughed, telling me of small acts of revenge she managed to inflict on her captors, she never smiled.

Before I left she turned her phone over to show me a passport photo inside the back cover. It was her as a smiling schoolgirl and the only thing she had left from a childhood in which she had never heard of the word rape. I need to believe I am still that girl, she said.

Maybe you think of rape as something that has always happened in war, that goes along with pillage. Ever since man has gone to war he has helped himself to the women, whether to humiliate his enemy, wreak revenge, satisfy his lust, or just because he canindeed rape is so common in war that we speak of the rape of a city to describe its wanton destruction.

As one of few women in a field that was still mostly male, I came into war reporting by accident and it was not the bang-bang that interested me but what went on behind the lineshow people keep life together and feed, educate, and shelter their children and protect their elderly while around them all hell is breaking loose.

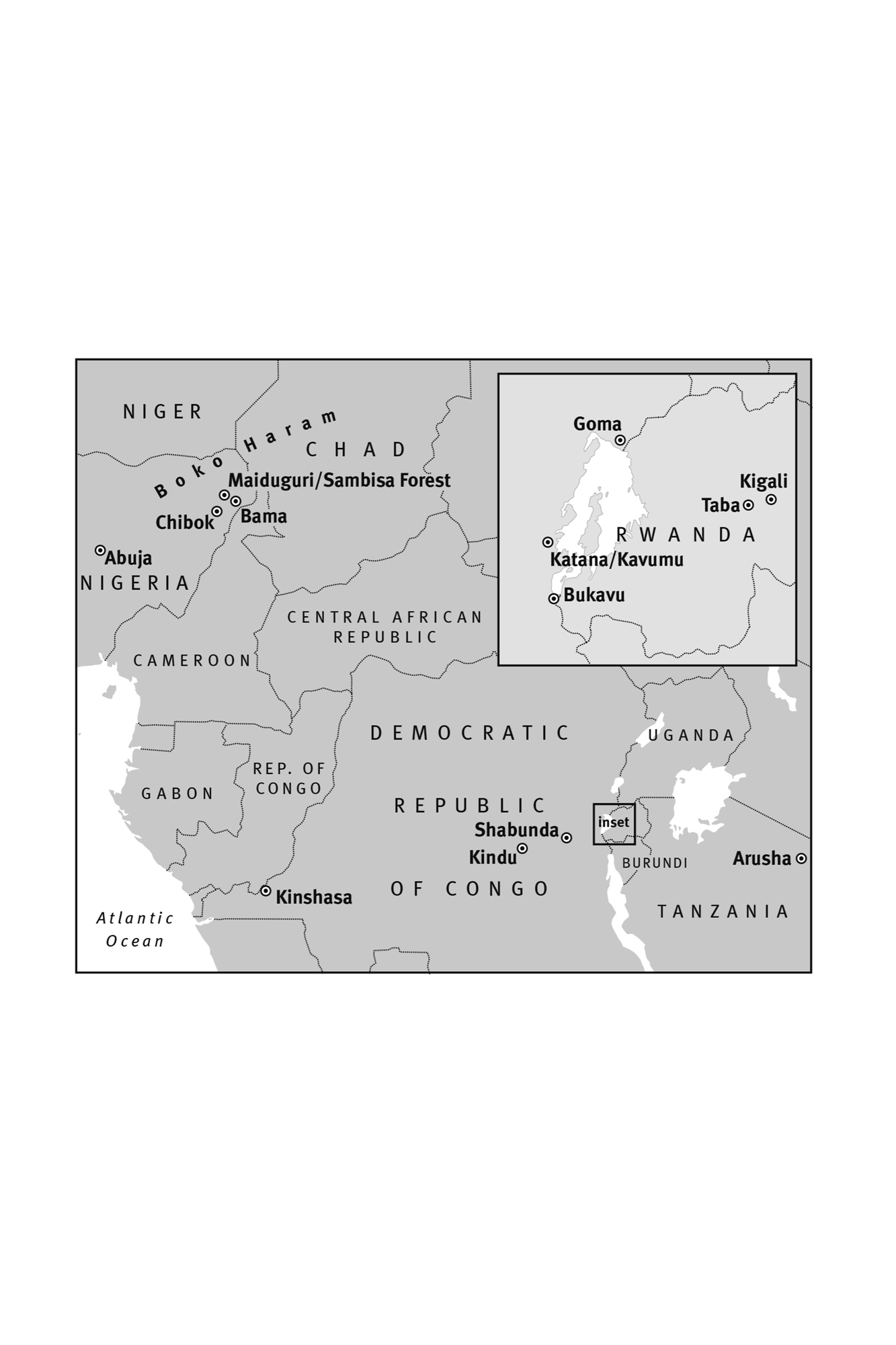

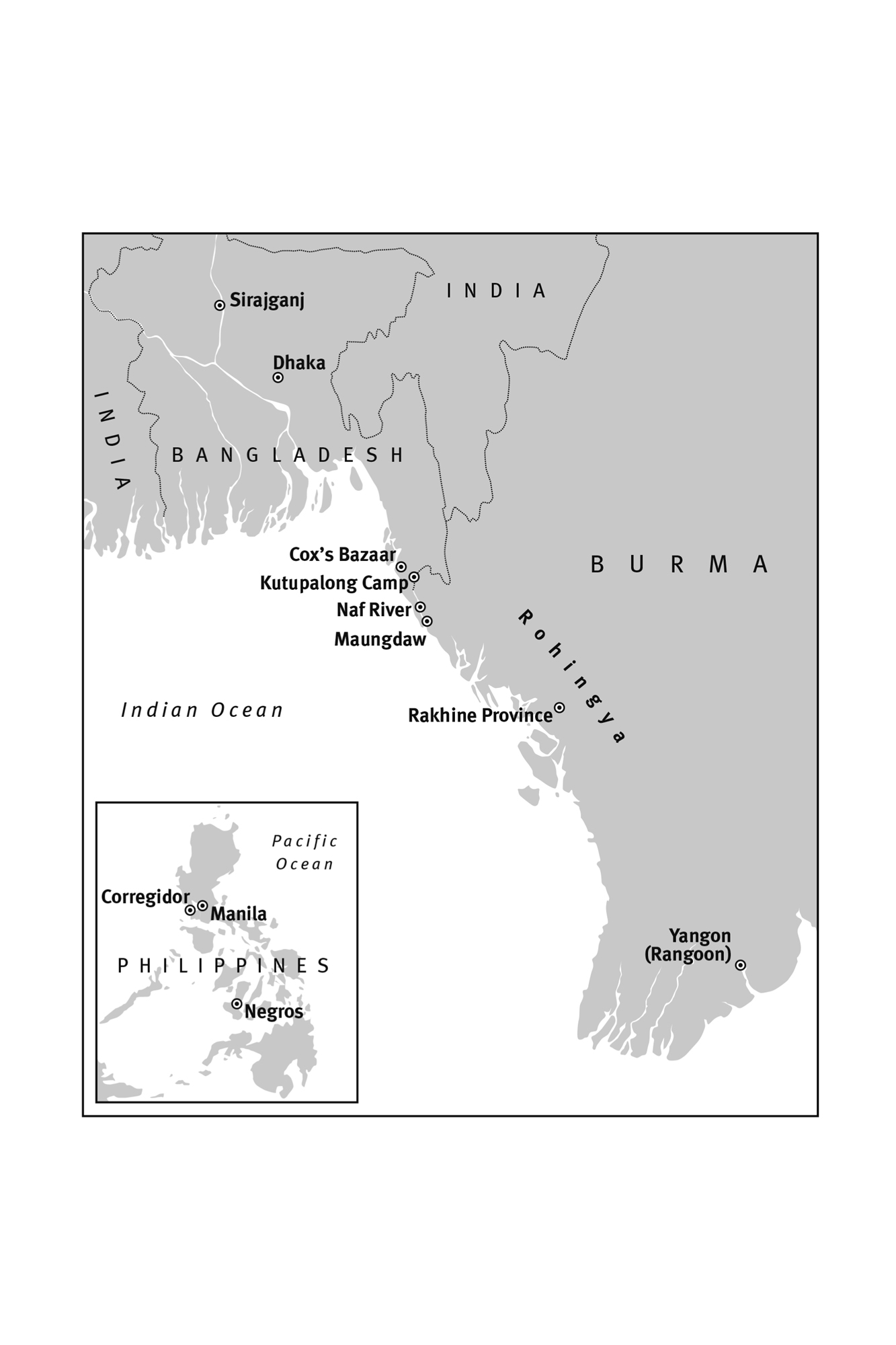

The Afghan mother telling me how she scraped moss from rocks to sustain her children as she shepherded them through the hills to escape bombing. The mothers under siege in the old city of East Aleppo who conjured up sandwiches for their children from fried flour and foraged leaves, and kept the children warm by burning furniture or window frames while streets around them were bombed into gray dust. The Rohingya women who carried their children through forests and across rivers to safety after Burmese soldiers massacred the men and burned down their huts.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Our Bodies, Their Battlefields»

Look at similar books to Our Bodies, Their Battlefields. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Our Bodies, Their Battlefields and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.