PENGUIN BOOKS

TWELVE YARDS

B EN L YTTLETON is a journalist and broadcaster who has written for Sports Illustrated and Time International, among others, and is Bloomberg TVs on-air soccer analyst. He is also a director of Soccernomics, the soccer consultancy. He lives in London. This is his first book.

Twelve

Yards

The Art and Psychology of the Perfect Penalty Kick

Ben Lyttleton

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by Bantam Press, an imprint of Transworld Publishers, 2014

Published in Penguin Books 2015

Copyright 2014 by Benedict Lyttleton

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Lyttleton, Ben.

Twelve yards : the art and psychology of the perfect penalty kick / Ben Lyttleton.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-18837-2

1. Passing (Soccer) 2. SoccerPsychological aspects. I. Title.

GV943.9.P37L98 2015

796.334dc23

2014038915

Cover design & illustration: Oliver Munday

Version_1

TO ABC, WITH LOVE

PROLOGUE

Shay Given is a man of few words, and when he was twenty, even fewer. The goalkeeper had just signed for Newcastle United when I went to Dublin to interview him before his debut for the club, a friendly against PSV Eindhoven. He was a little anxious about his first appearance, having spent the previous season on loan at Newcastles rivals Sunderland. Celtic, his first club, were possible opponents in the final of this preseason tournament at Lansdowne Road.

I told him I was nervous too. His glove manufacturers had arranged for me to compete in a sudden-death penalty shoot-out at halftime with Packie Bonner in goal. Bonner was an Irish legend, still playing at Celtic (it was his presence that forced Given to look elsewhere for games) and immortalized for one save: a dive to his right that kept out Romanian defender Daniel Timoftes penalty kick in a shoot-out at the 1990 World Cup. That one moment changed Bonners life: when David OLeary scored, Ireland reached the quarterfinal for the first (and so far only) time in their history.

Given perked up. Ah, youre taking a penalty against Packie. Good luck thenyoull need it.

I appeared to have taken his mind off his worries, but he had hardly helped mine.

Give me some advice then, I said. What should I do?

The first thing is, dont change your mind. Decide where youre going to kick it, and stick with it. And when Packies in goal, dont play silly games. No use trying to psyche him out.

When game day arrived, I tried to remember Givens words. Newcastle were 21 up at halftime, but the game had barely registered. I was standing next to the tunnel as the players walked off and I tried to catch Givens eye. That didnt work. My mind had gone blank. Had he told me to change my mind or not to change my mind? Did he say I should try to psyche out Bonner, or not? My brain was turning to mush, and I was not yet on the pitch.

I consoled myself with the fact that, as it was preseason, there were only 25,000 fans at Lansdowne Road; and as it was halftime, most of them would be getting a cup of tea, nipping to the loo or reading the match program. I was wrong. Bonner, of course, was an Irish hero and as many fans had turned up to glimpse him as to watch the game. I was quite surprised when one of my penalty opponents (there were three of us competing) was booed when he placed the ball on the spot. Fans behind the goal tried to put him off by waving and jumping. One dropped his trousers and flashed his bottom. It didnt work: he kept his head down and, off a long run-up, hit the ball hard and low to Bonners right. Goal.

I was next up. I also kept my head down, and slowly put the ball on the spot. I took three steps back, and looked up. Deep breath. The goal looked big. But so did Bonner. Another deep breath. I had recently rewatched the IrelandRomania shoot-out and noticed that Bonner dived to his right when players took shorter run-ups. It made sense: to generate power off a short run-up, a player is more likely to strike the ball to his natural side (that is, a right-footed player would kick to the keepers right).

One more breath, a little skip, and I was off. My first movement was a step to the left to widen the angle of my run-up. After three steps forward, I opened my body and struck the ball cleanly with my instep. I can still see the slight curl on the ball as it headed for the inside of the side-netting, the dream target for a striker. Bonner, whose first movement was a step to his right, was wrong-footed. I had wrong-footed Packie Bonner! On his home turf, no less! I wanted to tell Given what had happened. I wondered if he had been watching on a monitor in the dressing room.

The drama wasnt over. My last opponent had missed, and I was left with another kick to stay in the competition. My mentality was different now. Nervous tension had given way to confidence. Confidence had been supplanted by arrogance. I knew I was going to score this one. Bonners legs had gone. He couldnt read me. I had him just where I wanted him. And this time, in front of his adoring fans, I was going to show him.

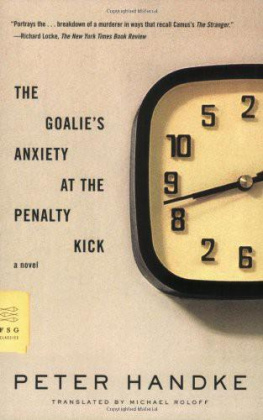

I chose a straighter run-up this time, slightly longer. It suggested power, and a kick to Bonners right. Instead, I wanted to attempt a chip down the middle, known as a Panenka after Antonin Panenka, the Czech midfielder whose penalty won the 1976 European Championship finalthe first and last time a German national side lost a shoot-out. I later discovered that Panenka had spent two years working on that one kick, on the disguise, the run-up, the contact and the pace of the shot. I had never even practiced it.

It showed. As I approached the ball, my feet got in a tangle. My left foot was too far from the ball for me to kick it, and when I took another step forward, I stumbled. I was leaning over the ball when my right foot made contact, and it rolled apologetically toward Bonner in the center of the goal. Had he not been there it might not even have crossed the line. It was my Icarus moment. I, not Bonner, had been humiliated. I could not even hear the crowd cheer, jeer or laugh; they must have felt sorry for me. That didnt help either.

In the space of five minutes I had endured the glory and the pain of penalties. There were more nuances behind the penalty battle between goalkeeper and striker than I realized: body language, how to spot the ball, eye contact, angle of run-upand thats only what you see before the ball has been kicked. I had underestimated the mental battle, not so much with the goalkeeper but within myself; and of course, like a true Englishman, I had failed to practice correctly. Well, I was hardly going to be able to re-create the same atmosphere and pressure in my back garden, was I?

Not that I hadnt tried. The majority of my childhood soccer memories, from a playing point of view at least, involve penalty kicks. I would spend hours taking penalties at home, using a sponge-ball and a radiator for a goal. It was a form of fantasy soccer: Id choose two teams in my head, pick five kickers from each team, and replicate a shoot-out. My response to those players every weekend was invariably based on how they had performed in my home-game shoot-outs. As I got older, I took the game to the park, and to friends houses: the same rules, with imagined players, but this time a goalkeeper to get past. I thought my sponge-ball practice had given me the edgebut it was not quite enough to beat Bonner twice.